Anal Anatomy

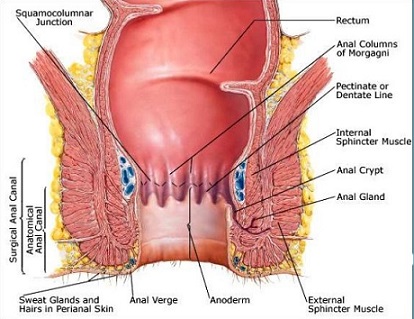

- Anal Canal

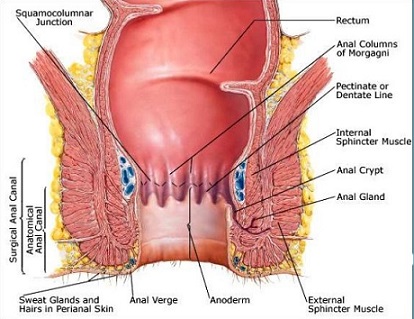

- anal verge is the junction between the anoderm and perianal skin

- dentate line is the mucocutaneous junction located 4 cm above the anal verge

- mucosa distal to the dentate line is a modified squamous epithelium devoid of hair and glands

- mucosa proximal to the dentate line is columnar epithelium

- the change between the 2 types of mucosa is not abrupt; there is a transitional zone that extends

for a variable length, from ~ 6 mm below to 20 mm above the dentate line

- anatomic anal canal extends from the anal verge to the dentate line

- surgical anal canal extends from the anal verge to the anorectal ring

- anorectal ring is the lower border of the puborectalis muscle that is palpable on rectal exam –

located 1.0 to 1.5 cm above the dentate line

- posteriorly, the anal canal is attached to the coccyx by the anococcygeal ligament

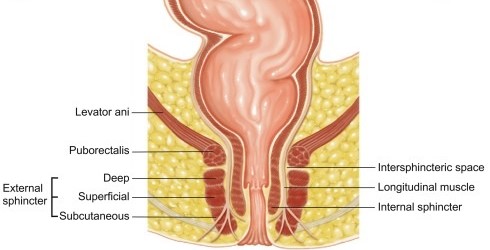

- Anal Sphincters

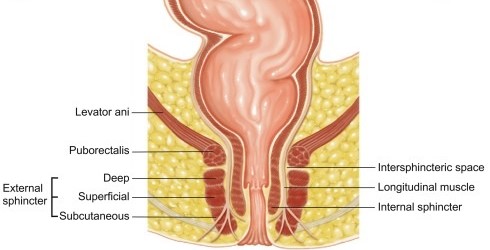

- Internal Sphincter

- continuation of the inner circular smooth muscle of the rectum

- involuntary muscle

- normally contracted at rest

- provides 80% of anal resting pressure

- major reflex response to rectal distention is relaxation

- External Sphincter

- voluntary muscle

- commonly divided into 3 parts: subcutaneous, superficial, and deep

- specialized continuation of the puborectalis muscle

- normally contracted at rest

- provides 20% of anal resting pressure and 100% of generated squeeze pressure

- its major reflex response to stimuli (postural change, rectal distention, increased intra-abdominal pressure)

is further contraction

- maximum voluntary contraction can only be maintained for 60 seconds before fatigue sets in

- Anal Glands

- body of the anal glands reside in the intersphincteric plane

- ducts of the glands penetrate the internal sphincter and terminate in the anal crypts

- anal crypts are located at the distal end of the columns of Morgagni, which consist of 8 to 14 mucosal folds

located above the dentate line

Anal Physiology

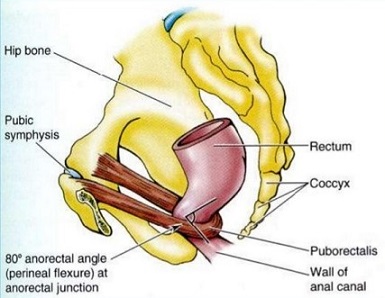

- Maintenance of Continence

- principal function of the anal canal is the maintenance of continence and the regulation of defecation

- principal mechanism that maintains continence is the pressure differential between the rectum (10 mm Hg) and the

anal canal (90 mm Hg)

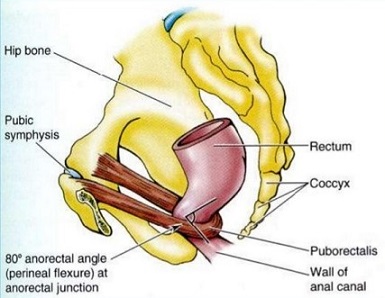

- also, contraction of the puborectalis muscle maintains the anorectal angle at 80°, so that it

functions as a flap valve

- continence also requires an adequate rectal capacity with normal compliance

- Defecation

- as feces accumulate in the rectum, the rectal wall distends to accommodate the fecal mass

- as the rectum distends, the internal sphincter relaxes and the external sphincter contracts

- relaxation of the internal sphincter allows the rectal contents to reach the anal canal

- once in the anal canal, sensory receptors located within the anal canal or pelvic floor musculature determine the

nature of its contents – flatus, liquid, or solid stool

- if defecation is to proceed, the external sphincter must be voluntarily relaxed, which also straightens the anorectal angle

- a voluntary increase in intra-abdominal pressure moves the contents of the rectum into the anal canal

- with selective relaxation of part of the external sphincter, it is possible to selectively pass flatus but not stool

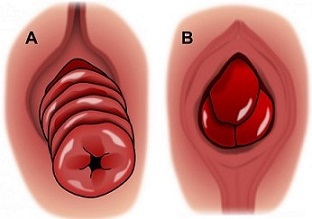

Rectal Prolapse

- Etiology

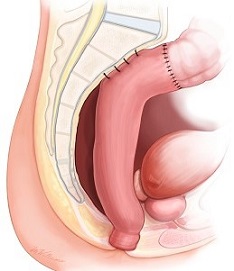

- complete prolapse is characterized by full-thickness eversion of the rectal wall through the anus

- partial prolapse involves prolapse of the mucosa only

- most commonly occurs in elderly women and institutionalized patients

- predisposing anatomic factors include a redundant rectosigmoid, deep pouch of Douglas, patulous anus,

diastasis of the levator ani, and lack of fixation of the rectum to the sacrum

- some studies suggest that intussusception is the primary cause, but what initiates the intussusception is not clear

- Clinical Manifestations

- a history of chronic constipation and straining is common

- most patients complain of the protrusion; in occult prolapse, a feeling of pressure and incomplete evacuation

may be the only symptoms

- many patients are incontinent

- chronically prolapsed mucosa may become ulcerated and cause significant bleeding

- digital rectal exam will usually reveal a patulous anus with poor sphincter tone

- a concomitant pelvic floor disorder (cystocele or prolapsed uterus) may also be present

- Diagnosis

- the best way to visualize the prolapse is to have the patient squat or sit on the toilet and strain

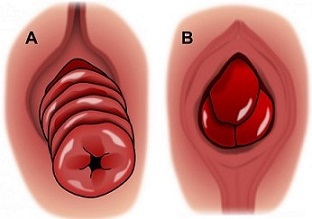

- seeing the concentric mucosal rings will help to differentiate prolapse from complicated hemorrhoidal problems

(radial folds)

- proctoscopy is mandatory and may demonstrate a polyp or cancer serving as the ‘lead point’ of the intussusception

- a complete colonoscopy or barium enema is necessary to rule out concomitant colon pathology

- anal manometry can document the degree of anal sphincter damage but does not influence the surgical procedure chosen

- defecography may help if the diagnosis is in question or if a concomitant pelvic floor disorder is suspected

- Surgical Options

- surgery is the mainstay of treatment

- can be managed from the perineal or abdominal approach

- the perineal approach is reserved for older patients who cannot tolerate a laparotomy

- abdominal procedures are associated with lower recurrence rates

- abdominal procedures can be done open or laparoscopically

- no ‘gold-standard’ procedure

- Narrowing of the Anus

- reserved for extremely high risk patients with incontinence

- prototypical procedure is the Thiersch-type anal encircling procedure using a synthetic mesh

- fecal impaction is the most common complication and laxatives and enemas are usually necessary postop

- wound infection and erosion of the mesh are also common

- procedure is rarely done now because of the high recurrence and complication rates

- Abdominal Procedures

- associated with lower recurrence rates than perineal procedures

- consists of rectal mobilization, ± sigmoidectomy, and rectal fixation

- Anterior Resection with Rectopexy

- major advantage is resection of the redundant sigmoid colon, which will improve constipation

- also, the rectum becomes fixed and adherent to the sacral hollow, helping to reduce recurrence

- major risk is anastomotic leak

- most surgeons will suture the rectum to the presacral fascia as a way of ensuring rectal fixation

- some surgeons also obliterate the cul-de-sac by suturing the endopelvic fascia anteriorly to the rectum

- both constipation and incontinence are improved by this procedure

- Rectal Fixation without Resection

- indicated when sigmoid resection is not required (no constipation)

- may be performed with sutures or mesh

- Suture Rectopexy

- the rectum is fully mobilized down to the levators and secured to the sacral fascia with

nonabsorbable sutures

- must avoid the presacral veins and nerves

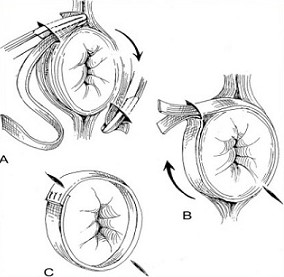

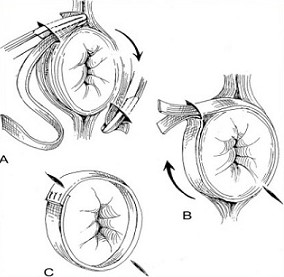

- Mesh Rectopexy

- the mesh is secured to the sacrum and then sutured to the rectum

- multiple options exist for fixing the mesh to the rectum

- obstruction and mesh erosion are complications

- Perineal Procedures

- usually reserved for patients who will not tolerate a laparotomy

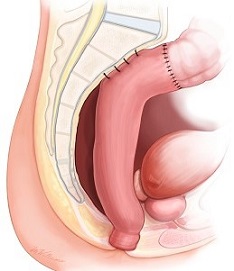

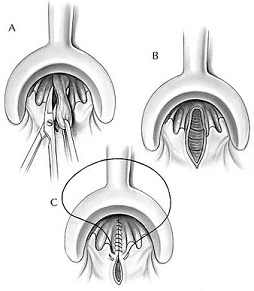

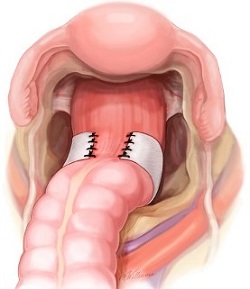

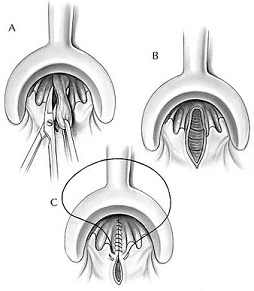

- Perineal Rectosigmoidectomy (Altemeier Procedure)

- for technical reasons, the length of the prolapse should be greater than 3 cm

- full-thickness circumferential incision is made in the prolapsed rectum 1 - 2 cm above

the dentate line

- cut edge of the rectum is pulled down and the mesorectum divided

- redundant rectum is then divided and an anastomosis is made to the anal ring

- the levator muscles may be plicated anteriorly for additional support

- recurrence rates appear to be high with this approach, probably because the rectum is

not fixed to the sacrum

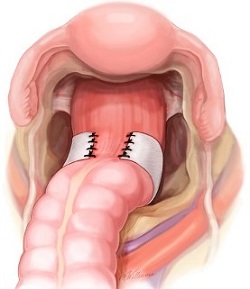

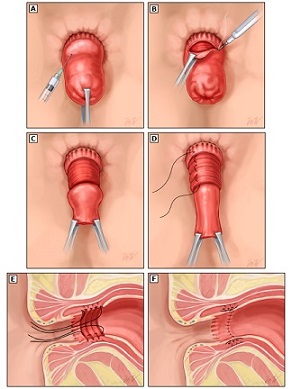

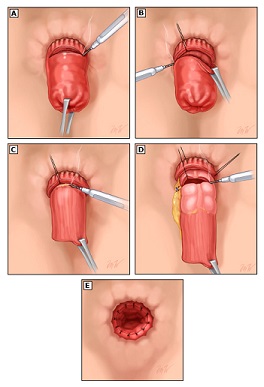

- Delorme Procedure

- reserved for patients with short prolapses

- not a full-thickness resection, but rather a resection of the redundant mucosa 1 – 2 cm proximal

to the dentate line

- the muscle layer is then plicated

- an anastomosis is then made between the mucosa at the level of the transection and the incision

proximal to the dentate line

- some surgeons will also plicate the levator muscles

Hemorrhoids

- Pathophysiology

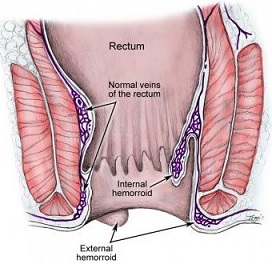

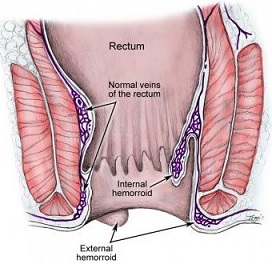

- Internal Hemorrhoids

- arise from specialized vascular and connective tissue cushions located in the left lateral, right anterior,

and right posterior positions in the anal canal

- consist of dilated arteriovenous channels (superior hemorrhoidal plexus) and connective tissue

- since they originate above the dentate line, internal hemorrhoids are covered by columnar mucosa which is

not sensitive to pain or touch

- by filling with blood during defecation, the cushions protect the anal canal from injury and aid in maintaining continence

- hemorrhoids refer to the abnormal enlargement of these cushions

- there are many theories as to what causes hemorrhoids: 1) downward displacement or prolapse caused by

straining, 2) destruction of the anchoring connective tissue system, 3) abnormal venous distention,

4) increased anal sphincter tone

- External Hemorrhoids

- originate below the dentate line and are covered by anoderm, which is very sensitive to pain

- arise from the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus

- since the superior and inferior hemorrhoidal plexuses communicate with each other, mixed hemorrhoids are common

- Clinical Manifestations

- Internal Hemorrhoids

- typically cause painless, bright red bleeding after defecation

- may also cause anal pruritis

- may also prolapse and become incarcerated

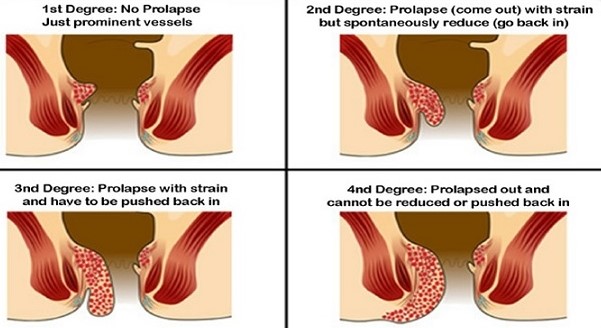

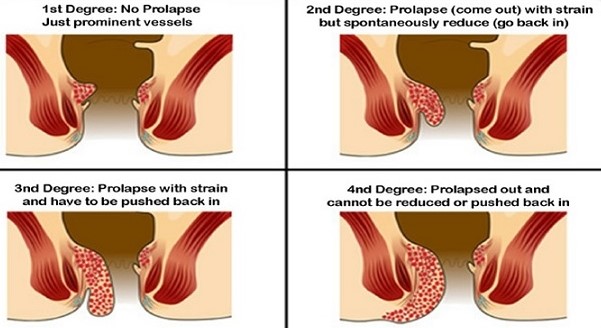

- Classification

- first degree: visible on anoscopy but do not prolapse below the dentate line

- second degree: prolapse out of the anal canal during defecation but spontaneously reduce

- third degree: require manual reduction

- fourth degree: incarcerated

- External Hemorrhoids

- may cause symptoms by swelling

- thrombosis may cause severe pain

- skin tags may form, which represent prior thrombosed hemorrhoids which have become organized into

fibrous appendages

- Diagnosis

- anoscopy is the definitive test

- consider screening colonoscopy if the patient is anemic, has risk factors for colon cancer or is due for

routine screening, or the hemorrhoidal disease is unimpressive

- Treatment

- Medical Therapy

- most patients with first- and second-degree hemorrhoids are adequately treated with bulking agents,

stool softeners, and increasing fluid intake

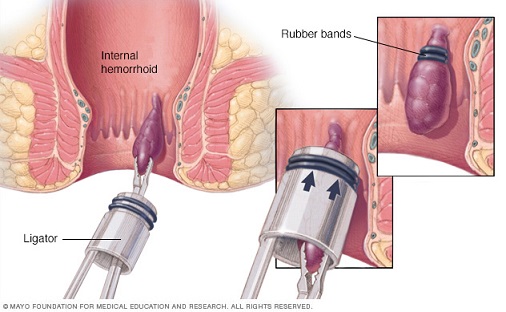

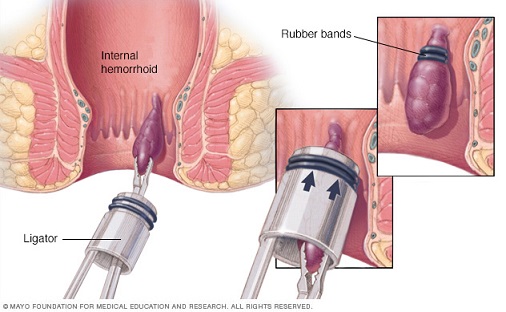

- Elastic Band Ligation

- effective treatment for most cases of second- and third-degree hemorrhoids

- can only be used on internal hemorrhoids – placement of elastic bands on anoderm or transitional epithelium is

extremely painful

- a single ligation may be done in the office every 2 weeks

- rarely, severe pelvic sepsis (pain, fever, difficulty voiding) has been reported after this procedure

- Sclerotherapy

- involves injection of a sclerosant (3% normal saline) into the internal hemorrhoid

- useful in patients who are on anticoagulants or who are immunocompromised or coagulopathic

- can treat all the hemorrhoids at one setting

- no need to stop the anticoagulants

- good short-term efficacy, but the recurrence rate is high

- Hemorrhoidectomy

- indications include large third-degree hemorrhoids, fourth-degree hemorrhoids, acutely thrombosed

hemorrhoids, gangrenous hemorrhoids

- may be done as an open or closed technique

- dissection must be superficial to the internal sphincter muscles

- a bridge of intact skin and mucosa should be left between excised hemorrhoid sites to avoid anal stenosis

- acutely thrombosed external hemorrhoids are best treated with excision not incision

- complications include urinary retention (30%), fecal incontinence (2%), infection (1%),

delayed hemorrhage (1%), and stricture (1%)

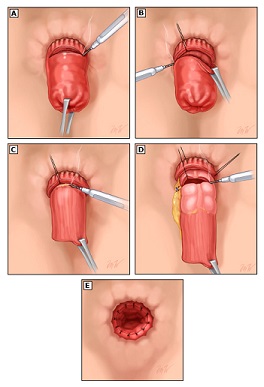

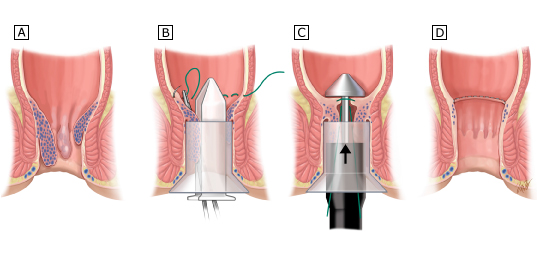

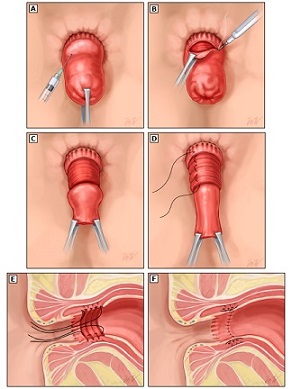

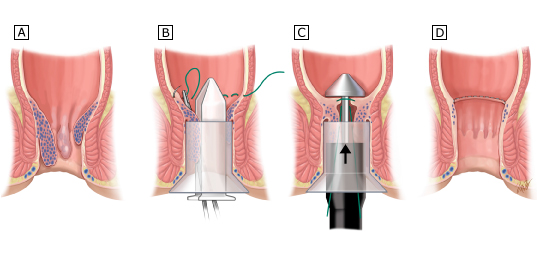

- Stapled Hemorrhoidopexy

- involves a circular resection and anastomosis of a 1- to 2-cm ring of anorectal mucosa and submucosa

- operation divides the vascular pedicles, resuspends the prolapsing tissue at the anorectal ring,

preserves the vascular cushions (important for continence), and avoids painful perianal wounds

- exact purse-string suture placement is crucial

- if the suture is placed too deep, then the vaginal wall may be incorporated anteriorly; if the suture is

placed too close to the dentate line, then severe intractable pain may result

- procedure is associated with higher patient satisfaction than conventional hemorrhoidectomy, but the

recurrence rates are also higher

- cannot be used for external hemorrhoids

- Special Problems

- Strangulated Hemorrhoids

- injection of dilute epinephrine together with 150 to 200 IU of hyaluronidase aids in reducing edema

and greatly facilitates the procedure

- must take care to preserve viable anoderm

- Pregnancy

- hemorrhoids often exacerbated in the 3rd trimester

- usual approach is conservative: Sitz baths, fiber, stool softeners

- often resolve spontaneously after delivery

- acutely thrombosed hemorrhoids can be operated on in the left lateral position

- Portal Hypertension

- anorectal varices are seen in 80% of patients with portal hypertension, but only account for 1% of massive

GI bleeding

- direct suture ligation may be tried

- TIPS procedure or portosystemic shunts may be required

References

- Sabiston 20th ed., pgs 1394 - 1402

- Cameron, 10th ed., pgs 190 - 194, 255 - 261

- UpToDate. Overview of Rectal Procidentia (Rectal Prolapse). Madhulika Varma, MD, Scott R. Steele, MD.

Mar 05, 2019. Pgs 1 – 22.

- UpToDate. Surgical Approach to Rectal Procidentia (Rectal Prolapse). Madhulika Varma, MD, Scott R. Steele, MD.

Sep 30, 2019. Pgs 1 – 38.

- UpToDate. Surgical Treatment of Hemorrhoidal Disease. David Rivadeneira, MD, Scott Steele, MD. Dec 03, 2019. Pgs 1 – 28.