Clostridioides Difficile Colitis

Clostridioides Difficile Colitis

- Bacteriology

- C. difficile is a gram-positive, spore-forming, toxin-producing, anaerobic bacteria

- most commonly associated with antibiotic use and disruption of the normal microbiome

- pathogenetic strains produce two toxins (A and B) that are responsible for the symptoms of

C. difficile infection (CDI)

- hypervirulent strains have emerged that produce 16X to 20X more toxin than less virulent strains

- pathogen most responsible for nosocomial infectious diarrhea

- Infection Risk Factors

- prior treatment with antibiotics, especially fluoroquinolones, clindamycin, cephalosporins, and penicillins

- antibiotics suppress the normal colon flora, allowing overgrowth of C. difficile

- other risk factors include age > 65, current or recent hospitalization, and use of proton pump inhibitors

- Clinical Presentation

- infection (CDI) can vary from mild diarrhea to fulminant infection with toxic megacolon and systemic sepsis

- infection typically begins within 4 to 9 days after starting antibiotics

- 25% of patients may present up to 10 weeks after a course of antibiotics

- Mild Disease

- main symptom is watery diarrhea – more than 3 loose stools / 24 hrs

- other symptoms include lower abdominal pain and cramping, low-grade fever, anorexia, and nausea

- physical exam may demonstrate lower abdominal tenderness

- average WBC count is 15,000

- Severe Disease

- diffuse abdominal pain and distention

- hypovolemia, elevated creatinine, and lactic acidosis are common

- WBC count may be as high as 40,000

- Fulminant Disease

- hypotension may progress to shock and multisystem organ failure

- toxic megacolon

- bowel perforation with peritonitis

- WBC count may be > 50,000

- Recurrent Disease

- 25% of patients relapse within 30 days of completing treatment

- recurrent disease can be mild, severe, or fulminant

- one major risk factor for recurrence is the ongoing need for concomitant antibiotics

during treatment for CDI

- Asymptomatic Carriers

- 20% of hospitalized patients are asymptomatic carriers

- no need to screen for these patients, and no need for treatment or contact precautions

- Diagnosis

- Stool Studies

- CDI is diagnosed by a positive test for C. difficile toxins or the C. difficile toxin B gene

- there are several diagnostic tests available, each with their advantages and disadvantages

- GDH Antigen Test

- uses antibodies to test for the GDH enzyme, a protein present in all C. difficile species

- cheap and fast

- a negative test is useful (good sensitivity)

- a positive test, however, cannot distinguish between toxigenic and nontoxigenic strains

(poor specificity)

- Toxin A and B Test

- low cost, fast turnaround

- both toxins should be tested for

- a positive test is valuable (high specificity)

- high rate of false negatives (low sensitivity)

- Interpretation of Results

- if both tests are positive, then the patient should be treated for CDI

- if both tests are negative, then the patient does not have CDI

- discordant results (one test positive, the other negative) should be resolved with the NAAT test

- NAAT Test

- polymerase chain reaction test for the gene encoding toxin B

- a positive test is considered evidence of CDI, as long as one of the first two tests was also positive

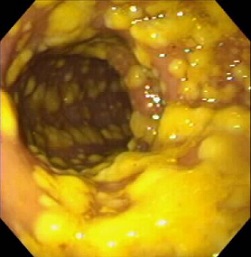

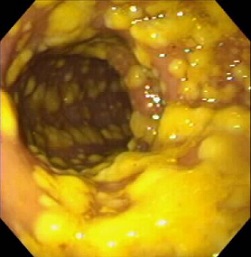

- Endoscopy

- not usually necessary unless another diagnosis is suspected that requires direct visualization

and/or biopsy

- flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may identify the plaque-like pseudomembranes which are pathognomonic

for CDI

- pseudomembranes are found in 25% of patients with mild disease, and 87% with fulminant colitis

Pseudomembranes

Pseudomembranes

- Management

- Medical Management

- Infection Control

- initiate hospital infection control practices

- contact precautions

- hand-washing with soap and water may be more effective than alcohol-based hand sanitizers since

C. difficile spores are resistant to alcohol

- Antibiotic Management

- discontinue the offending antibiotics if possible

- if continued antibiotic treatment is necessary, then switching to other agents less frequently

implicated in CDI is prudent

- Diarrhea Management

- correct fluid and electrolyte losses

- antimotility agents (loperamide and opiates) are usually avoided, but the evidence that they

cause harm is not strong

- patients can have a regular diet as tolerated

- Treatment

- Mild Disease

- oral vancomycin is the preferred antibiotic

- oral fidaxomicin and oral metronidazole are alternatives

- treatment course is for 10 days

- Severe or Fulminant Disease

- higher doses of antibiotics are used

- a second agent may be added if no response

- drugs may need to be given via an NG tube

- in refractory cases, vancomycin can be given as an enema, but is associated

with perforation

- Surgery

- Indications

- toxic megacolon

- perforation

- failure of medical management with ongoing systemic toxicity

- Procedures

- Total Abdominal Colectomy with End ileostomy

- indicated for perforation, necrosis, or abdominal compartment syndrome

- residual infection in the rectal pouch may be managed with vancomycin flushes

through a rectal tube

- since CDI is a pancolonic disease, segmental colectomy is not indicated for isolated

areas of perforation or necrosis

- Diverting Loop Ileostomy with Colonic Lavage

- since the mortality rate of abdominal colectomy and ileostomy is so high (34% to 57%),

other surgical options have been explored

- one promising procedure is laparoscopic loop ileostomy creation with intraoperative

antegrade colonic lavage using polyethylene glycol

- the fluid is collected with a rectal tube

- postoperatively, vancomycin irrigation through the ileostomy is continued for 10 days

- associated with lower mortality and higher ileostomy reversal rates in nonrandomized

studies than total abdominal colectomy

Ischemic Colitis

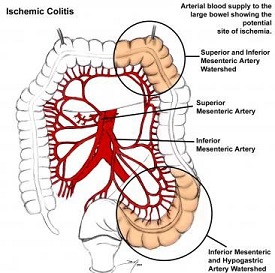

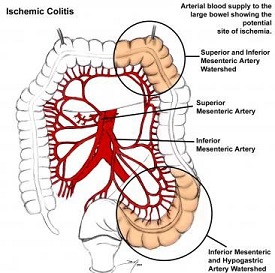

- Anatomy

- colon receives its blood supply from the SMA and IMA

- SMA gives off the ileocolic, right colic, and middle colic arteries

- IMA gives off the left colic, sigmoid, and superior rectal arteries

- rectum also gets blood supply from the iliac arteries via the inferior and middle rectal vessels

- SMA and IMA have an extensive collateral network that limits the risk of colon ischemia

- Collateral Connections

- marginal artery of Drummond forms a continuous arcade near the colon wall

- in some patients, the arc of Riolan connects the SMA, via the middle colic, with the IMA, via the left colic

- Watershed Areas

- regions of the colon that have limited collateral blood flow

- splenic flexure (Griffith's point) is where the SMA and IMA circulations meet

- rectosigmoid junction (Sudek's point) is where the distal sigmoid arteries and superior rectal artery meet

- Etiologies

- Occlusive Causes

- thromboembolism, usually from atrial fibrillation

- IMA ligation during aortic reconstruction

- Nonocclusive Causes

- accounts for 95% of cases of colon ischemia:

- heart failure

- arrhythmias

- shock

- vasopressors

- cardiopulmonary bypass

- Classification

- Partial Thickness

- ischemia limited to the mucosa and submucosa

- usually resolves with nonoperative management

- may result in stricturing and scarring

- Full Thickness

- perforation is common

- urgent surgery is necessary

- Clinical Presentation

- left-sided abdominal pain, cramping, low-grade fever, bloody diarrhea is typical of partial thickness disease

- full thickness ischemia can result in peritonitis, high fever, leukocytosis, acidosis

- Diagnosis

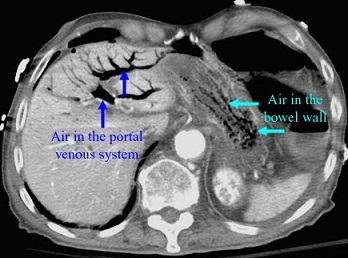

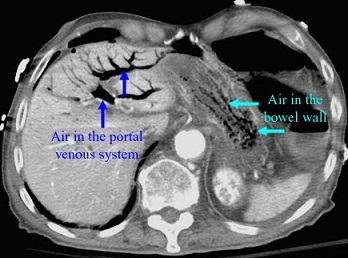

- Plain Films

- most valuable for detecting free air or pneumatosis, and for ruling out obstruction

- Lab Studies

- no specific marker for ischemia

- elevated lactate, LDH, CPK, or amylase suggest significant tissue damage

- CT Scan

- best study is with IV and oral contrast, if possible

- valuable for ruling out nonischemic causes of abdominal pain

- suggestive, but nonspecific, findings of ischemia include colon wall thickening,

pneumatosis, pericolonic fat stranding, portal venous air

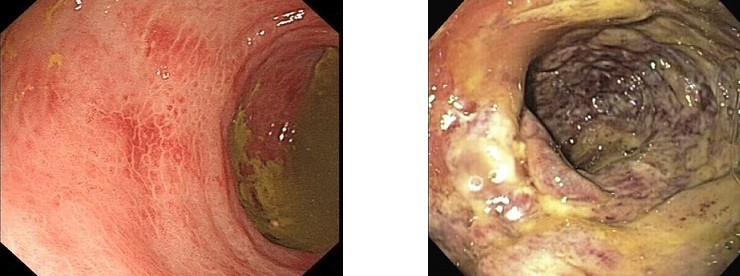

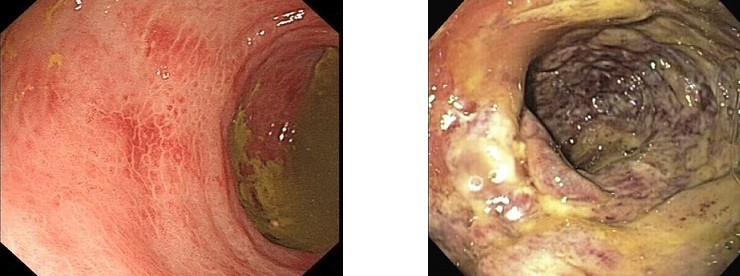

- Endoscopy

- allows direct vision of the colon mucosa

- cannot reliably distinguish between mucosal ischemia and full-thickness ischemia

- partial thickness ischemia is suggested by hemorrhagic, pale mucosa with patches

of inflammation interspersed between areas of healthy mucosa

- full thickness ischemia is suggested by dusky mucosa, submucosal hemorrhage,

hemorrhagic ulcerations or frank necrosis

(L) Partial thickness ischemia

(R) Full thickness ischemia

(L) Partial thickness ischemia

(R) Full thickness ischemia

- Angiography

- only role is if embolism is suspected

- Treatment

- Nonoperative Management

- nearly 80% of patients respond to conservative therapy:

- NPO

- fluid resuscitation for low flow states

- NG tube for nausea, vomiting

- broad-spectrum antibiotics to prevent translocation of bacteria

- discontinue vasopressors if possible

- goal is to maximize cardiac output and mesenteric blood flow

- failure to improve within 24 – 48 hours should mandate repeat CT scan or endoscopy

- Surgery

- indications include peritonitis, free air, massive hemorrhage, or evidence of full thickness

necrosis on imaging or endoscopy

- revascularization procedures are not indicated

- open or laparoscopic segmental resection with an ostomy or mucous fistula is the usual procedure

- primary anastomosis should be avoided in this patient population

- consider a second look procedure if there is concern for ongoing ischemia

- if the entire colon is involved, then total colectomy and ileostomy is necessary

References

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 1353 – 1359

- Cameron 11th ed., pgs 169 – 172, 173 – 177

- UpToDate. Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) Difficile Infection in Adults: Treatment and Prevention.

Ciaran P. Kelley MD, et. al. Jan 30, 2020. Pgs 1 – 35.

- UpToDate. Surgical Management of Clostridioides (Formerly Clostridium) Difficile Colitis in Adults.

Brian Zuckerbraun, MD. Jan 21, 2019. Pgs 1 - 16.

- UpToDate. Colonic Ischemia. Peter Grubel, MD, et. al., Mar 05, 2020. Pgs 1 – 35.