Colon and Rectum Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy

- Colon

- General Anatomy

- outer longitudinal muscle layer is separated into 3 distinct strips called taeniae coli,

positioned 120° apart

- haustra are sacculations between the taeniae and have a characteristic appearance on x-ray

- appendices epiploicae are fatty appendages attached to the taeniae

- Cecum

- blind pouch projecting from the ascending colon

- terminal ileum enters the cecum at the ileocecal valve

- has the largest internal diameter of any part of the colon (7 to 9 cm)

- usually is completely enveloped by peritoneum and lies free in the abdomen

- because of its large diameter, tumors may become large and bulky and rarely present with

obstructive symptoms

- most common site of colon rupture caused by distal obstruction (Laplace’s law: T = PR)

- appendix generally projects from the inferior aspect of the medial portion

- Ascending Colon and Hepatic Flexure

- posterior walls are retroperitoneal in location

- right ureter and duodenum may be injured during mobilization

- Transverse Colon

- completely intraperitoneal

- very mobile; suspended by the transverse mesocolon

- attached to the stomach by the gastrocolic omentum

- the omentum is attached to its anterosuperior edge

- Splenic Flexure

- usually more cephalad than the hepatic flexure

- composed of the phrenocolic and splenocolic ligaments

- Descending Colon

- posterior wall is retroperitoneal

- Sigmoid Colon

- intraperitoneal; attached to the sigmoid mesentery

- left ureter lies at the base of the sigmoid mesentery

- may be very redundant

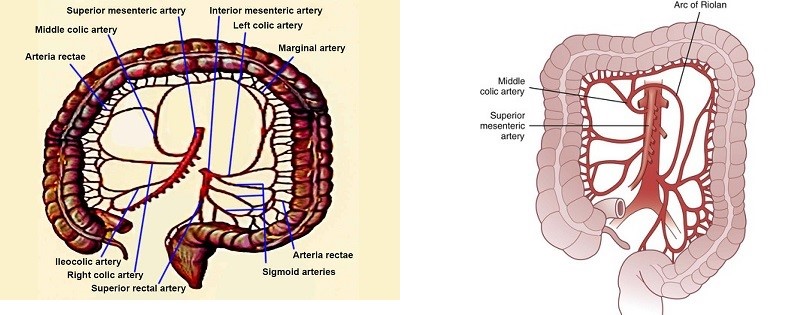

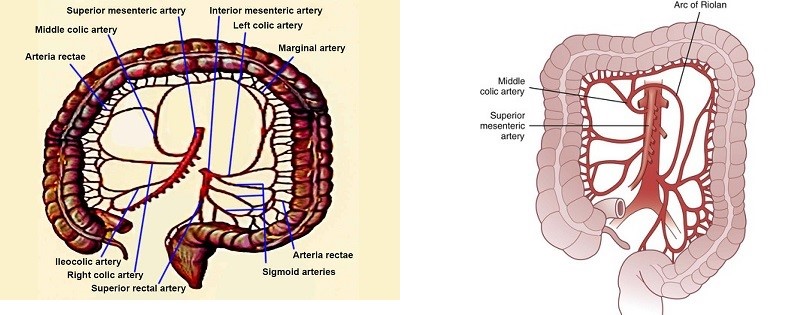

- Blood Supply and Lymphatic Drainage

- Arterial Supply

- superior mesenteric artery supplies the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon via

its ileocolic, right colic, and middle colic branches

- inferior mesenteric artery supplies the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and upper rectum via

its left colic, sigmoidal, and superior rectal branches

- the main vessels of the colon bifurcate and form arcades that are connected in a collateral

network by the marginal artery of Drummond

- marginal artery of Drummond runs along the mesenteric border of the colon and provides

the vasa recta to the colon

- the arc of Riolan is an inconstant vessel that connects the left colic with the middle colic artery

- Watershed Areas

- refers to areas of the colon that receive blood supply from the most distal branches

of two main arteries

- if one of the two arteries is occluded, ischemia rarely results because the patent vessel

is able to supply that area

- however, during systemic hypoperfusion, these areas are particularly vulnerable to ischemia

because they are supplied by the most distal branches of the main arteries

- incomplete anastomoses of the marginal artery also contribute to the vulnerability of the watershed areas

- the splenic flexure is the watershed area of the SMA and IMA (Griffith’s point)

- the rectosigmoid region is the watershed area of the IMA and internal iliac artery (Sudeck’s point)

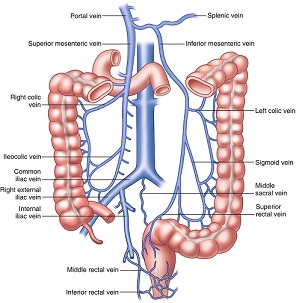

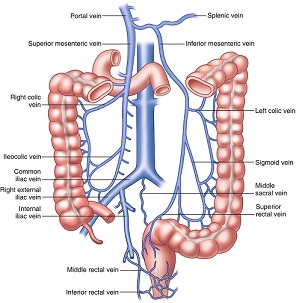

- Venous Drainage

- superior mesenteric vein drains the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon and joins the splenic vein

to form the portal vein

- inferior mesenteric vein drains the descending colon, sigmoid, and upper rectum

- inferior mesenteric vein runs in a retroperitoneal location to the left of the ligament of Treitz

and behind the pancreas to join the splenic vein

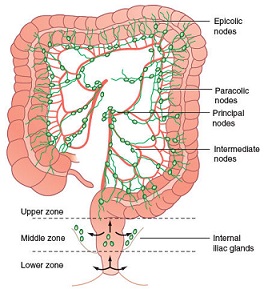

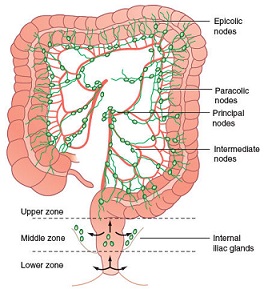

- Lymphatic Drainage

- lymphatic channels are located in the submucosa of the bowel wall

- lymphatic vessels follow the arterial supply of the colon

- lymph nodes are located on the bowel wall (epicolic), along the inner margin of the bowel

(paracolic), along the named arteries (intermediate), and near the origin of the superior

and inferior mesenteric arteries (main)

- Rectum

- General Anatomy

- at the rectosigmoid junction (sacral promontory), the taeniae coalesce and form a complete longitudinal

muscle layer

- rectum contains 3 distinct curves: the proximal and distal curves are convex to the right, and the middle curve

is convex to the left

- these curves project into the lumen as the valves of Houston

- anterior peritoneal reflection usually is about 7 to 9 cm from the anal verge in men, and 5 to 7.5 cm in women

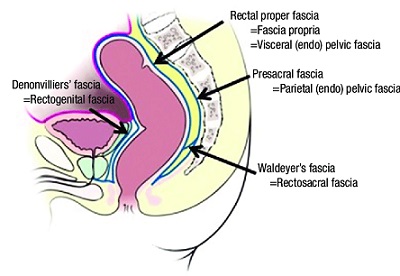

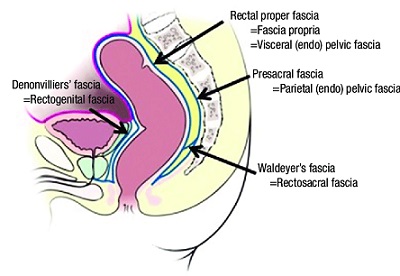

- Fascia and Ligaments

- Waldeyer’s fascia is a dense fascia covering the sacrum and overlying the vessels and nerves

- it extends anteriorly to the rectum

- Denonvilliers’ fascia is a double fascial layer that is firmly attached to the prostate and

seminal vesicles and loosely attached to the rectum

- the lateral ligaments are thickenings of endopelvic fascia that support the lower rectum and may

contain the middle rectal arteries

- Pelvic Floor

- musculotendinous sheet formed by the levator ani muscle

- pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles make up the levator ani muscle

- innervated by the fourth sacral nerve

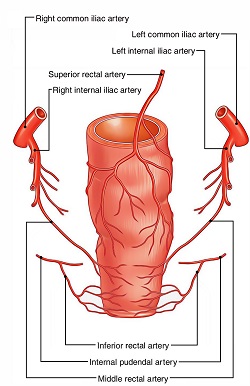

- Blood Supply and Lymphatic Drainage

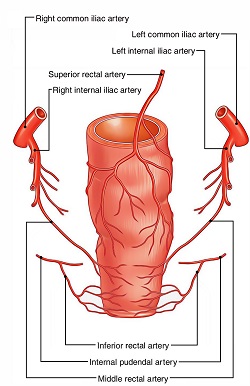

- Arterial Supply

- superior rectal artery, the terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery,

supplies the upper and middle rectum

- middle rectal arteries arise from the internal iliacs and supply the middle and lower rectum

- inferior rectal arteries are branches of the internal pudendal arteries and supply the

internal and external sphincter muscles

- Venous Drainage

- upper and middle rectum drain into the superior rectal vein, which enters the portal system via the

inferior mesenteric vein

- lower rectum drains into the middle rectal veins, which enter the systemic venous system via the

internal iliac veins

- inferior rectal veins drain the lower anal canal and empty into the pudendal veins

- Lymphatic Drainage

- follows the arterial supply

- upper and middle rectum drains into the inferior mesenteric nodes

- lower rectum may drain into the inferior mesenteric nodes or into the iliac and paraaortic nodes

- Nerve Supply

- Sympathetic Nerves

- rectum, bladder, and sexual organs receive sympathetic innervation via the hypogastric nerve

- Paraympathetic Nerves

- originate from the second, third, and fourth sacral roots (nervi erigentes)

Physiology

- Colon

- Absorption

- Water

- 1000 to 1500 cc of water enters the cecum per day

- only 100 to 150 cc of water per day is lost in the stool (90% reabsorption)

- under maximum conditions, the colon can absorb 5 to 6 liters of fluid per day

- most absorption occurs in the ascending colon

- Sodium

- colon is able to absorb sodium against very high concentration gradients

- colon may absorb up to 400 mEq of sodium per day

- Chloride

- actively absorbed against a concentration gradient

- exchanged with bicarbonate at the luminal border

- patients with a ureterosigmoidostomy are prone to developing hyperchloremia and metabolic acidosis

due to the absorption of urinary chloride in exchange for bicarbonate

- Bile Acids

- colon participates in the enterohepatic circulation

- anaerobic bacteria convert the primary bile salts, cholate and chenodeoxycholate, into secondary

bile salts, deoxycholate and lithocholate

- some deoxycholate is passively reabsorbed in the colon

- Short Chain Fatty Acids

- produced by fermentation of dietary fiber by colonic bacteria

- preferential energy source for colonic epithelial cells

- Ammonia

- colonic bacteria degrade protein and urea to produce ammonia

- ammonia diffuses across the colonic mucosa and reaches the liver via the portal circulation

- ammonia absorption decreases as the intraluminal pH falls

- ammonia absorption can contribute to the encephalopathy of patients in liver failure

- lactulose is administered to encephalopathic patients because it reduces the colonic bacterial load

by causing an osmotic diarrhea and it decreases ammonia absorption by lowering the colonic luminal pH

- Secretion

- Electrolytes

- both potassium and bicarbonate are secreted by colonic epithelium

- Diarrhea

- bacteria, enterotoxins, and hormones can stimulate fluid and electrolyte secretion in the colon,

resulting in diarrhea

- Motility

- Retrograde Movements

- contractile waves originating in the transverse colon and traveling towards the cecum

- purpose is to delay the transit of material from the right colon, thus increasing the absorption

of fluids and electrolytes

- Segmental Contractions

- most common motility pattern

- colonic contents are separated into a series of globular masses

- may play a role in the development of sigmoid diverticula

- High Amplitude Contractions (Mass Movements)

- most infrequent type of motility pattern, occurring 3 or 4 times per day

- antegrade propulsive contractile wave involving a long segment of colon

- each contraction lasts 20 to 30 seconds and generates colonic pressures of 100 to 200 mm Hg

- advances the colonic contents through one third of the colonic length

- rectum undergoes receptive relaxation to accommodate the stool until defecation occurs

- Microbiology of the Colon

- Colonic Microflora

- colon is sterile at birth but within hours becomes colonized from the environment in an oral to

anal direction

- contains over 400 bacterial species

- bacteria account for one half of the dry weight of stool

- each gram of stool contains 1011 to 1012 bacteria

- anaerobes outnumber aerobes by a factor of 102 to 104

- bacteroides species are the most common anaerobes, Escherichia coli is the most common aerobe

- colonic bacteria provide many important functions:

- suppress emergence of pathogenic organisms

- produce short-chain fatty acids from undigested carbohydrates (fermentation)

- participate in the metabolism of many substances that are then recycled by the enterohepatic

circulation (bile acids, bilirubin, estrogen, cholesterol)

- synthesizes vitamin K

Bowel Preparation

- Rationale

- if strict criteria are used, the incidence of postoperative wound infection after elective colon resection

may be as high as 20%

- the rationale for bowel preparation is that decreasing the bacterial load by mechanical bowel preparation

and decreasing the bacterial concentration by oral antibiotics will decrease the incidence of postoperative wound infections

- the value of preoperative bowel preparation remains unclear, and several randomized trials

have shown no benefit from mechanical bowel preparation, oral antibiotics, or both

- however, in spite of a lack of evidence supporting bowel preparation, only 25% of elective colectomies are

performed with no preoperative bowel prep

- Components

- Mechanical Bowel Preparation

- rids the colon of solid stool, thereby decreasing the bacterial load

- most common regimens use polyethylene glycol (PEG or Go-lytely) or magnesium citrate the night

before surgery

- PEG solutions require large volumes and often cause nausea, bloating, and cramping resulting in

poor patient compliance

- dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities are also common complications

- sodium phosphate-based preparations require lower volumes and may be better tolerated

- Oral Antibiotics

- most common regimen uses oral neomycin and erythromycin base in three repeated doses

(1, 2, 11 pm) the day before surgery

- greatly reduces the concentration of gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria in the colon

- many surgeons have abandoned oral antibiotics because they can cause significant GI symptoms,

which also reduces compliance with the mechanical prep

- also, since most patients receive a dose of IV antibiotics before incision, the value of the oral antibiotics in reducing

wound infections is unclear

Ostomies

- Definition

- surgical anastomosis between the GI tract and the skin

- may be elective or emergent, permanent or temporary, loop or end

- most commonly constructed with the sigmoid colon or terminal ileum

- it should be kept in mind that every temporary ostomy is a potential permanent ostomy

- Technical Details

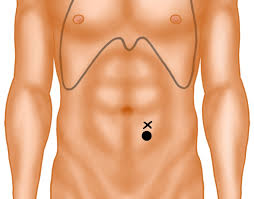

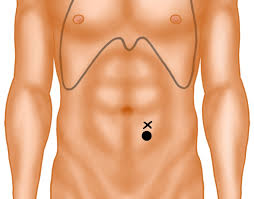

- Site

- a poorly placed stoma can be a source of misery to the patient

- the stoma must be visible to the patient and easily accessible

- it should be placed through the rectus muscle, well away from the costal margin and iliac crest,

and below the belt line

- in elective cases, a preoperative consult with an enterostomal therapist will greatly assist preoperative

siting, as well as counseling and education

- in emergency cases, a reasonable location for the stoma is two-thirds along the line from the anterior superior

iliac spine and umbilicus

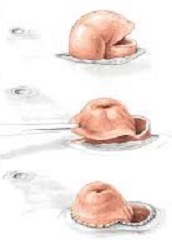

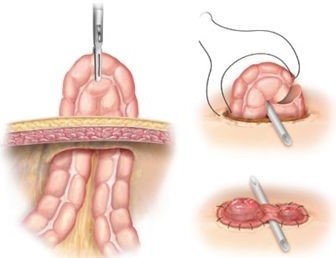

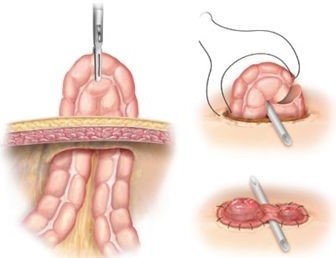

- Technique

- a circular skin incision is made and the subcutaneous fat is removed down to the anterior rectus sheath

- the anterior sheath is incised in a cruciate fashion, the muscle fibers split bluntly, and the posterior

sheath opened to admit 2 - 3 fingers

- the colon or ileum is then brought through the defect without tension and secured to the skin

- must avoid injuring the inferior epigastric artery

- Ileostomy

- Permanent (End) Ileostomy

- Indications

- destruction of the anal sphincter mechanism after proctocolectomy for Crohn’s disease or

ulcerative colitis

- total abdominal colectomy with no planned reanastomosis

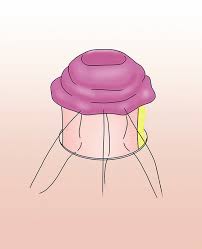

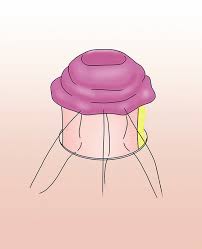

- Technique

- Brooke’s technique should be used to create a nipple that protrudes 2 - 3 cm above the skin

- this technique allows more reliable drainage into the pouch and minimizes skin excoriation

and breakdown

- Temporary (Loop) Ileostomy

- Indications

- most common indication is to ‘protect’ an anastomosis that is felt to be at high risk of breakdown

- these include low rectal anastomoses, anastomoses in an irradiated field, or high risk

(malnourished or immunocompromised) patients

- the primary advantage of a loop ileostomy is that closure usually does not require another laparotomy

- Technique

- the proximal end can be everted in Brooke fashion and the distal end left flush to the skin

- some surgeons will support the loop with an underlying rod that can be removed in 5 – 7 days

- Complications

- excessive fluid and electrolyte loss is common and is treated with bulking agents and opioids

(Lomotil, Imodium)

- skin irritation and breakdown may occur with poorly fitting appliances or poorly constructed stomas

- parastomal hernias and prolapse are late complications that usually require operative repair or

resiting of the stoma

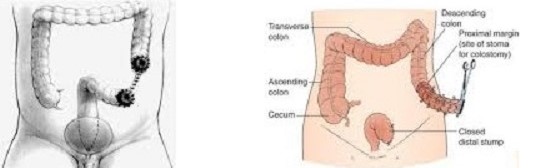

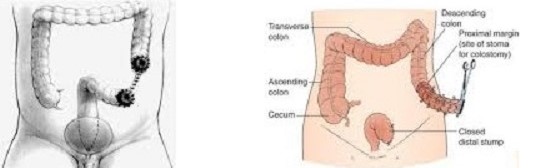

- Colostomy

- End Colostomy

- may be used as a permanent or temporary colostomy

- Indications

- abdominoperineal resection for a low rectal cancer

- permanent fecal incontinence (paraplegia)

- perforated diverticulitis

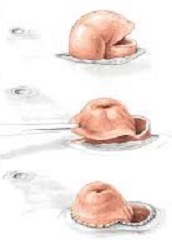

- Technique

- most are created using the left side of the colon

- most are secured flush to the skin, but some surgeons prefer a Brooke technique

- the distal bowel may be left intraabdominally as a Hartmann’s pouch (most common) or

brought out on the abdominal wall as a mucus fistula

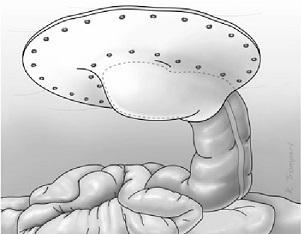

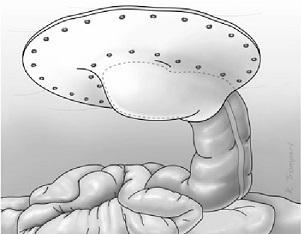

- Loop Colostomy

- Indications

- most commonly used as a ‘diverting’ colostomy to decompress a colon obstructed from

cancer or diverticular disease

- may also be used to facilitate healing of decubitus ulcers or complicated perianal wounds

- since the sigmoid and transverse colons are the most mobile segments of the colon, they are

the most common sites chosen

- Technique

- a large defect in the abdominal wall needs to be made

- the colon is usually supported with a rod or bridge for 5 – 7 days

- because of the size of the colon, applying an appliance can be difficult

- Complications

- poor blood supply can lead to necrosis

- retraction can occur if there is too much tension and is often related to a thick abdominal wall

- parastomal hernia is a late complication and requires repair if symptomatic

- some surgeons advocate trying to prevent hernias by reinforcing the colostomy with mesh at the

original surgery – the mesh can be placed in an onlay, sublay, or intraperitoneal position

- prolapse can occur, usually with a loop colostomy

- skin complications are rare

References

- Schwartz, 10th ed., pgs 1175 - 1195

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 1312 – 1324

- Cameron, 11th ed., pgs 147 – 148

- UpToDate. Overview of Surgical Ostomy for Fecal Diversion. Todd D. Francone, MD, MPH, FACS. May 09, 2019. Pgs 1 - 54

- UpToDate. Overview of Colon Resection. Miguel A. Rodriguez-Bigas MD. Sep 09, 2019. Pgs 3 - 7