Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- Pathophysiology

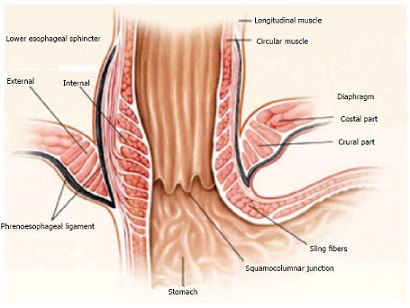

- Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) Physiology

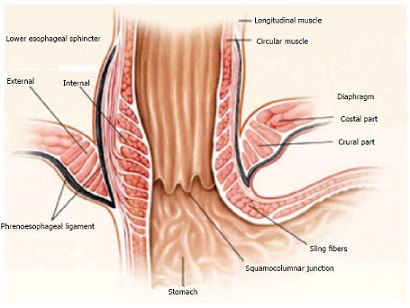

- not a distinct anatomic structure, but rather a high pressure zone

- muscles of the distal esophagus are tonically contracted, and relax when a swallow is initiated

- sling fibers of the gastric cardia, which are at the same depth as the circular muscle fibers of the

esophagus but are oriented in a different direction, also contributes to the esophageal high-pressure zone

- the diaphragm contributes to LES pressure by compressing the esophagus when it contracts

- positive intraabdominal pressure also contributes to LES pressure

- Decreased LES Pressure

- Transient Loss of LES Pressure

- LES is structurally normal

- responsible for ‘physiologic’ reflux

- results from gastric distention secondary to overeating,

stress aerophagia, delayed gastric emptying, increased intragastric or increased intraabdominal pressure

- gastric distention pulls open the LES and reduces its overall length

- when a critical length is reached, between 1 and 2 cm, LES pressure drops markedly and reflux occurs

- after gastric venting occurs, sphincter length is restored and competence returns until further distention

again shortens the LES

- Permanent Loss of LES Pressure

- results from structural damage to the components of the LES: loss of pressure, inadequate overall length, or loss of abdominal length

- reduced LES pressure is most likely due to an abnormality of myogenic function (length and tension properties of the LES’s

smooth muscle)

- the efficacy of a LES with normal pressure can be nullified by an inadequate abdominal length or overall length

- an adequate abdominal length is important in preventing reflux caused by increases in intraabdominal pressure

(exertion or changes in body position)

- an adequate overall length is important in preventing reflux caused by gastric distention

- Ineffective Esophageal Clearance

- an effective esophageal pump clears the esophagus of physiologic reflux

- four factors are important in esophageal clearance of gastric juice: gravity,

esophageal motor activity, salivation, and anchoring of the distal esophagus in the abdomen (hiatal hernia)

- ineffective esophageal clearance is usually seen in association with a structurally defective LES, which augments

the esophageal exposure to gastric juice by prolonging the duration of each reflux episode

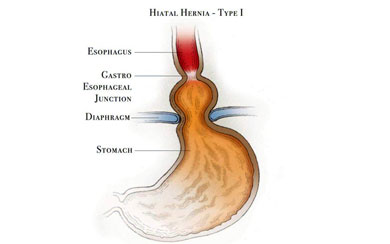

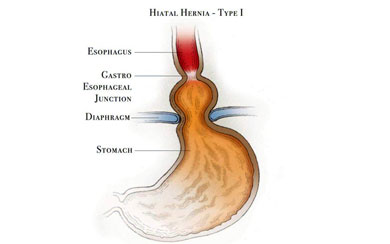

- Hiatal Hernia

- sliding (type I) is the most common hiatal hernia associated with reflux

- occurs when the phrenoesophageal ligament does not maintain the GEJ in the abdominal cavity

- there is a strong association between GERD and hiatal hernia: most patients with GERD have a hiatal hernia, and

the larger the hernia the greater the amount of acid reflux

- however, not every patient with reflux has a hiatal hernia; and not every patient with a hiatal hernia has reflux

- Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms

- most common symptoms are substernal heartburn (early) and acid regurgitation (late)

- however, these symptoms are very common in the general population and may be caused by many other

diseases besides GERD

- also, GERD may present with atypical symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness,

chest pain, chronic cough, wheezing, asthma, or recurrent pneumonia

- using clinical criteria alone to define GERD lacks sensitivity and specificity

- to make the diagnosis of GERD, objective evidence is required (endoscopy, pH probe, Barrett’s esophagus)

- Complications of GERD

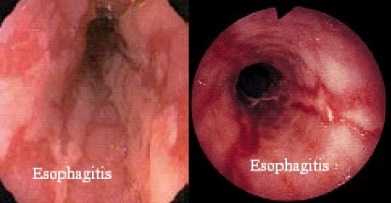

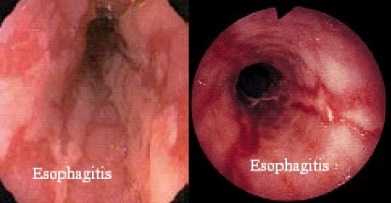

- Esophagitis

- repeated injury and repair leads to fibrosis and progressive deterioration of esophageal contractility

- stricture and Barrett’s esophagus are the end stages of chronic esophagitis

- Stricture

- most common symptom is dysphagia

- need to rule out tumor, motor disorder, diverticula

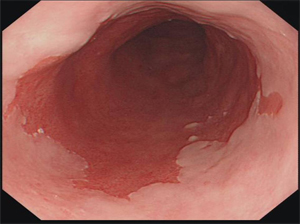

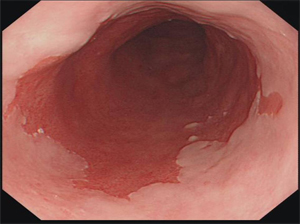

- Barrett’s Esophagus

- defined as the pathological replacement of the esophagus’ normal

stratified squamous epithelium with an intestinal-like columnar epithelium (intestinal metaplasia)

- caused by chronic esophageal injury and inflammation

- represents an increased risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma (0.5% per year)

- Aspiration

- refluxed gastric juice can reach the pharynx

- symptoms include repetitive cough, choking, hoarseness, and recurrent pneumonia

- GERD may be responsible for pulmonary diseases such as asthma, pulmonary fibrosis, and bronchiectasis

- Treatment of GERD

- Empiric Medical Management

- patients with symptoms of heartburn without obvious complications can be given a 6 week trial of a proton pump

inhibitor (PPI) without further studies

- additional lifestyle interventions include elevating the head of the bed, avoiding tight clothing, eating small,

frequent meals, avoiding eating shortly before bed, losing weight, and avoiding alcohol, coffee and chocolate

- most patients (80%) have a recurrence of GERD after discontinuation of any type of medical therapy

- long-term complications of PPIs are being studied: nutritional deficiencies, infectious complications, gastric polyp formation,

osteoporosis

- Evaluation

- required for all patients being considered for surgery, as well as for patients with atypical symptoms or

possible complications

- Endoscopy

- very high specificity for diagnosing GERD, but lacks sensitivity – about 50% of GERD patients have normal

endoscopic findings

- severity of symptoms correlates poorly with the severity of esophagitis

- most useful for detecting complications of GERD (erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s metaplasia) and excluding other

diseases (cancer, stricture)

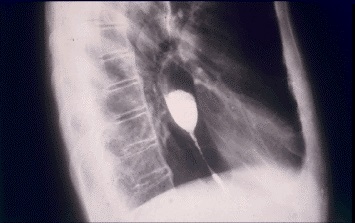

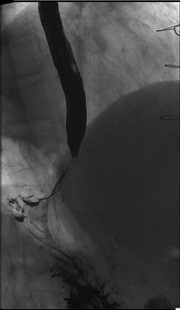

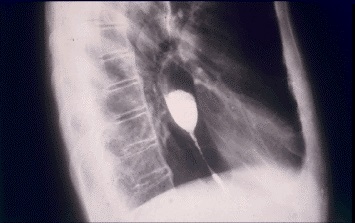

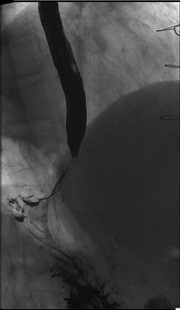

- Esophagram

- provides valuable information about the external anatomy of the stomach and esophagus

- provides information about the size and type of hiatal hernia that is present

- may show a ‘short’ esophagus

- Manometry

- if dysphagia or chest pain is present, then manometry is required to exclude an esophageal motility disorder

- fully assesses the adequacy of esophageal contractions

- findings may alter the surgical approach – patients who have weak peristalsis may need a partial fundoplication

instead of a complete wrap

- pH Monitoring

- gold standard for diagnosing and quantifying acid reflux

- allows symptoms to be correlated with reflux events

- patients need to discontinue PPIs one week before the test

- Operative Indications

- ideal candidate for an antireflux operation is a patient who responds well to

medical therapy but is unwilling or unable to continue the medicines (side effects, cost)

- severe esophagitis on endoscopy

- benign strictures

- Barrett’s metaplasia without untreated high-grade dysplasia

- since GERD requires lifelong medical therapy, surgery in younger patients is the more cost effective option

- absolute contraindications are esophageal cancer or Barrett’s esophagus with untreated high-grade dysplasia

- obesity is a relative contraindication, and these patients may benefit more from an obesity operation than a

fundoplication

- Principles of Surgical Treatment of GERD

- procedure chosen should restore the functional and mechanical competence of the LES, reconstruct the hiatus,

and repair any hiatal hernia if present

- must preserve the ability to swallow normally, and belch and vomit as necessary

- the following principles should be adhered to:

- restore the pressure in the LES to twice resting gastric pressure

- restore an adequate length of the LES to the positive-pressure environment of the abdomen (2.5 cm)

- allow the reconstructed cardia to relax on swallowing by avoiding injury to the vagus nerve and only using

the fundus for the wrap

- the fundoplication should not increase the resistance of the relaxed sphincter to a level that exceeds the

peristaltic power of the esophagus

- 360° wrap should be no longer than 2 cm and constructed over a 56 - 60 Fr bougie

- the fundoplication must be placed in the abdomen without undue tension and maintained there by approximating

the crura of the diaphragm above the repair

- Procedure Selection

- laparoscopic transabdominal approach is the preferred approach for most patients

- open transabdominal approach is reserved for patients who require a revisional reflux procedure, or who

have had multiple previous abdominal procedures, or any contraindication to laparoscopy

- transthoracic approach is used when a long esophageal myotomy is required for a primary motility disorder

- complete 360° wrap (Nissen)is preferred for most patients

- partial wraps (Toupet, Dor) are used when there is poor esophageal contractility

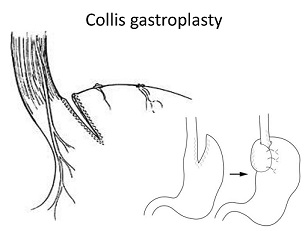

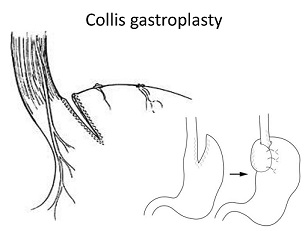

- a short esophagus will require extensive mediastinal mobilization and/or an esophageal lengthening

procedure (Collis Gastroplasty)

- Nissen Fundoplication

- important technical points include:

- retraction of the left lateral lobe of the liver

- identify and expose both crus

- divide the short gastrics

- identify and preserve both vagus nerves

- circumferential mobilization of the esophagus

- crural closure, but too tight can lead to dysphagia

- fundus is passed posterior to stomach, and a short wrap is created over a 56 – 60 Fr bougie

- some series report 90% of patients are symptom-free at 10 years

- Complications

- Esophageal or Gastric Perforation

- endoscopy at the end of the procedure may help to identify this problem

- post-op, patients with unexplained fever or tachycardia should have an UGI

to exclude a perforation or herniated wrap

- Dysphagia

- very common postop problem that usually resolves within several weeks

- persistent symptoms should be evaluated with an UGI

- if the wrap is too tight, serial endoscopic dilations usually resolves the problem

- occasionally, revision of the fundoplication to a partial fundoplication will be necessary

- Gas Bloat Syndrome

- abdominal pain, inability to belch

- caused by air trapping in the stomach

- creation of a short, floppy wrap will usually avoid this problem

- KUB shows a gas-filled stomach

- NG tube decompression immediately alleviates the symptoms

- dietary modifications and prokinetic agents are occasionally helpful,

but some patients will require conversion of their full wrap to a partial wrap

- a pyloroplasty may also benefit some patients with poor gastric emptying

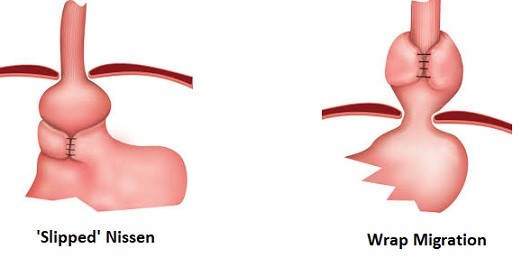

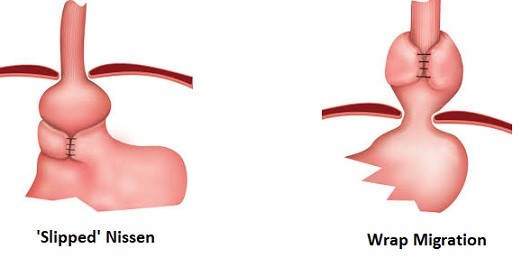

- Slipped or Misplaced Wraps

- if improperly secured to the esophagus, the wrap can slip down onto the body of the stomach,

leading to recurrent reflux symptoms or obstruction

- the wrap may also migrate into the thorax, leading to recurrence of reflux symptoms

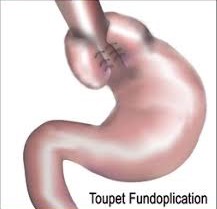

- Partial Fundoplications

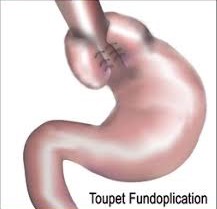

- Toupet Procedure

- 270° posterior wrap

- used for patients with documented esophageal motor abnormalities

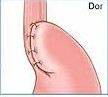

- Dor Procedure

- 180° anterior wrap

- similar indications and results as the Toupet procedure

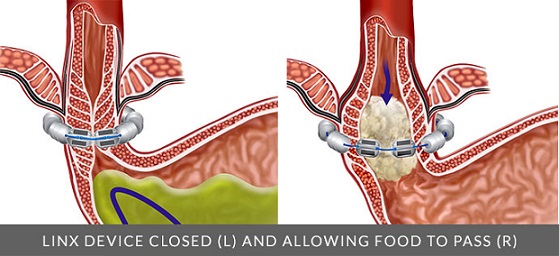

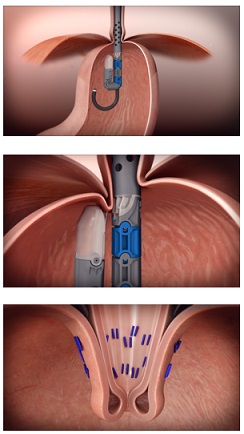

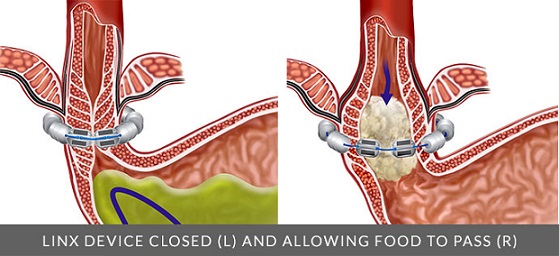

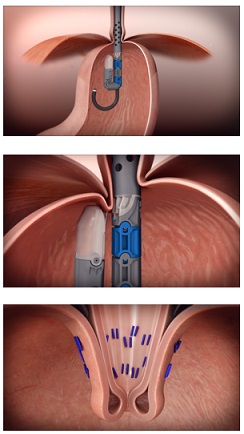

- LINX Prosthesis

- approved by the FDA in 2012

- surgically placed magnetic ring that augments the LES closure pressure but permits food passage

with swallowing

- contraindications include a large hiatal hernia or severe esophagitis

- short term follow-up suggests results similar to laparoscopic fundoplication, but 10 – 20 year

follow up data is not available yet

- some devices have been explanted secondary to dysphagia or esophageal erosion

- older devices are not MRI-compatible; new devices are MRI-conditional

- Endoscopic Approaches

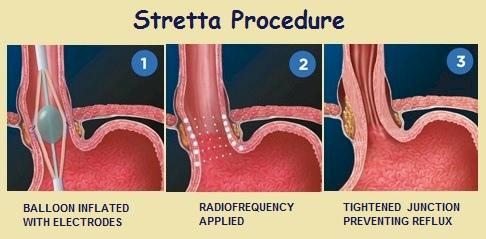

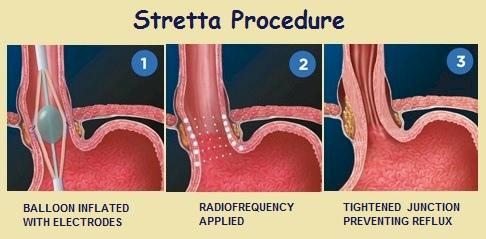

- Stretta Procedure

- radiofrequency energy is applied to the muscle of the LES and gastric cardia,

strengthening and thickening the muscle

- must have an LES pressure ≥ 8 mm Hg and a hiatal hernia < 3 cm long to be eligible

for the procedure

- Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication (Esophyx)

- full-thickness serosa-to-serosa plication that is 3 – 5 cm in length and 200 – 300 degrees in circumference

- questions remain about the long-term durability of the procedure

References

- Sabiston, 19th ed., pgs 1033 – 1036, 1067 – 1083

- Cameron, 11th ed., pgs 9 – 14, 19 – 23, 27 – 36

- UpToDate. Clinical manifestations and Diagnosis of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults. Kahrilas MD, Peter. March 2018. Pgs 1 – 21

- UpToDate. Surgical Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults. Schwaitzberg MD, Steven. Jan 02, 2019. Pgs 1 – 35