Esophageal Motility Disorders

Achalasia

- Pathophysiology

- ‘lack of relaxation’

- results from degeneration of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexuses of the esophageal wall,

which may be idiopathic (most common) or infectious (Chagas’ disease)

- the neurons that are primarily affected are inhibitory, resulting in unopposed smooth muscle stimulation and,

ultimately, failure of relaxation of the LES and aperistalsis

- hypertension of the LES leads secondarily to elevated esophageal pressure and esophageal dilatation

- some achalasia patients also have a defect in UES relaxation, leading to loss of the belch reflex

- premalignant condition (8% chance of developing cancer at 20 years)

- Presentation

- dysphagia for both solids and liquids that develops over many years

- regurgitation of undigested food

- use of large quantities of water to wash food down

- GERD-like retrosternal burning pain

- aspiration pneumonia common

- Diagnosis

- Barium Esophagram

- mild dilatation early, massive dilatation (megaesophagus) late

- peristalsis disordered early, nonexistent late

- retained intraesophageal contents typical

- classic finding is the ‘bird’s beak’ taper

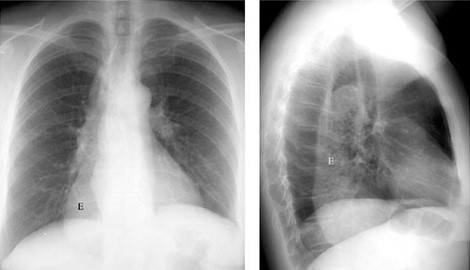

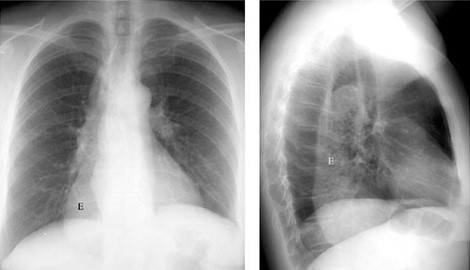

- Chest X-ray

- widened mediastinum

- posterior mediastinal air-fluid level

- absence of gastric air bubble

- Manometry

- gold standard test for diagnosis

- incomplete LES relaxation with swallowing

- elevated LES pressure (> 35 mm Hg)

- increased intraesophageal baseline pressure

- aperistalsis in the esophageal body

- low-amplitude waveforms indicating a lack of muscular tone

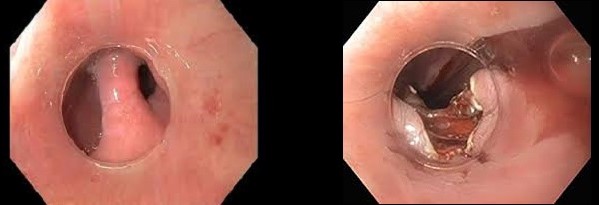

- Esophagoscopy

- useful to evaluate for esophagitis or the presence of carcinoma

- Therapy

- palliative, not curative

- treatment directed towards relieving the obstruction caused by a nonrelaxing LES

- no treatment addresses the decreased motility in the esophageal body

- Medical Therapy

- sublingual nitroglycerin, nitrates and calcium-channel blockers may help alleviate symptoms very early in

the disease, or in patients who are not candidates for more invasive treatments

- least effective treatment option

- Botulinum Toxin Therapy (Botox)

- injected directly into the LES during endoscopy

- most patients have early improvement in symptoms but require retreatment within 6 – 12 month

- Esophageal Dilatation

- hydrostatic or pneumatic balloons are used to dilate and rupture the fibers of the LES

- multiple endoscopies are required per treatment (graded approach)

- initial success rates are high (85%), but efficacy wanes over time

- main complication is esophageal rupture (4%) which has a 20% mortality rate

- procedure may be repeated when symptoms recur, but each subsequent dilation is progressively less

likely to result in a sustained remission

- often is the first treatment chosen

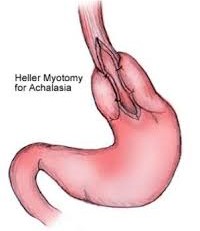

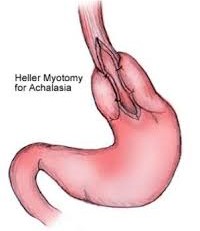

- Surgical Therapy

- esophageal myotomy is needed to relieve LES hypertension

- classic approach is the transthoracic left-sided open myotomy from the gastric cardia to the level of

the aortic arch

- procedure can also be done from a transabdominal approach

- laparoscopic and thoracoscopic approaches are now becoming standard

- an area of controversy is whether an anti-reflux procedure is necessary and which procedure should be done

- a complete 360-degree Nissen fundoplication has the potential to increase LES pressure and worsen symptoms of

esophageal obstruction - for this reason, a partial wrap (Toupet) is often chosen

- esophagectomy (transhiatal) should be considered for end-stage disease or failure of more than one myotomy

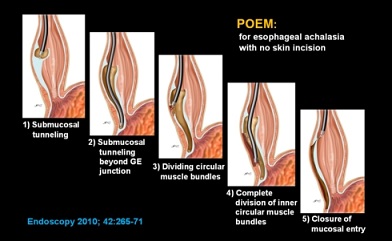

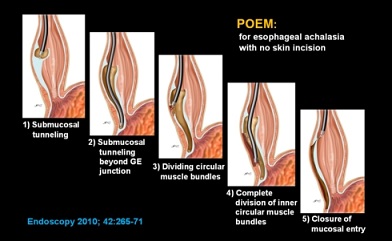

- Per-Oral Endoscopic Myotomy

- replicates the surgical procedure endoscopically

- no long-term follow up data yet

Distal (Diffuse) Esophageal Spasm

- Pathophysiology

- poorly understood hypermotility disorder

- motor abnormality of the lower two-thirds of the esophagus that may be related to impaired inhibitory innervation

- muscular hypertrophy and degeneration of branches of the vagus nerve have been observed

- esophageal contractions are repetitive, simultaneous, high-amplitude, tertiary

- Presentation

- chest pain, often mimicking angina pectoris by radiating into the neck or down the arm

- dysphagia for solids and liquids is common

- regurgitation of food is unusual

- may have other functional GI disorders (irritable bowel syndrome, pyloric spasm)

- Diagnosis

- initial evaluation usually is cardiac in nature (chest x-ray, EKG)

- esophageal etiology is often considered only after a negative cardiac workup

- need also to rule out intraabdominal pathology (gallstones, peptic ulcer)

- esophagoscopy is necessary to rule out a distal obstructing lesion that produces tertiary

contractions

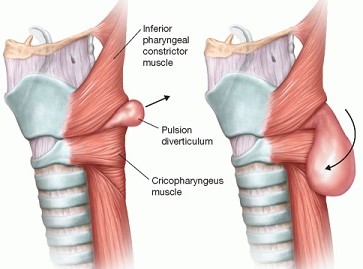

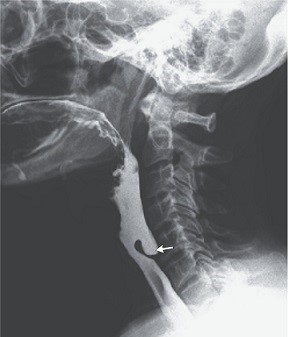

- barium esophagram may show a thickened esophageal wall (>5 mm), pulsion diverticulum, the classic ‘corkscrew’ esophagus,

or it may be normal

- manometry is the critical diagnostic test

- repetitive, simultaneous, high-amplitude or long duration tertiary contractions define spasm

- if standard or ambulatory manometry fails to demonstrate DES, provocative maneuvers (bethanecol) may induce

the motility disorder

- diagnostic goal is the correlation of subjective symptoms with objective evidence of spasm on manometry

- Treatment

- Medical Therapy

- avoid ‘trigger’ foods

- control GERD symptoms with PPIs

- antispasmodics are occasionally helpful (peppermint oil – Altoid mints)

- calcium channel blockers or nitroglycerine are occasionally helpful

- tricyclic antidepressants are helpful for some patients

- Endoscopic Therapy

- bougie dilation for severe dysphagia provides relief in 70% - 80%

- Botox injections may provide short-term relief

- Surgical Therapy

- results are much less favorable than in achalasia

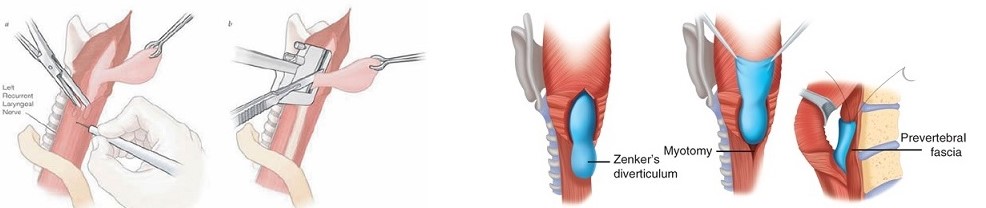

- esophagomyotomy should be used only in the most severe and refractory cases of dysphagia, or if a pulsion

diverticulum is present

- a long transthoracic myotomy is necessary, extending from the aortic arch onto the proximal stomach

- since the myotomy will make the LES incompetent, an anti-reflux procedure is necessary

- a 360-degree fundoplication is contraindicated, just as in the case in achalasia

Hypercontractile (Nutcracker) Esophagus

- Presentation

- symptoms are similar to DES: chest pain, dysphagia, odynophagia

- most painful of all esophageal hypermotility disorders

- Diagnosis

- barium swallow may show segmental spasm, or be normal

- manometry shows extremely high-amplitude (225 to 430 mm Hg) normally progressive peristaltic contractions, often of prolonged duration (> 6 seconds)

- LES pressure is normal and relaxes with each wet swallow

- manometry findings need to coincide with subjective complaint of chest pain

- ambulatory monitoring may be necessary to distinguish this disorder from DES

- Therapy

- medical management is the treatment of choice and is similar to the management of DES

- avoid trigger foods

- surgery rarely is indicated or helpful

Ineffective Esophageal Motility

- Pathophysiology

- contraction abnormality of the distal esophagus

- usually associated with GERD

- may be secondary to inflammatory injury to the esophageal body

- decreased motility of the esophageal body leads to poor acid clearance in the lower esophagus

- Symptoms

- reflux symptoms and dysphagia

- Diagnosis

- esophagram shows nonspecific abnormalities of esophageal contraction

- diagnosis made by manometry: nontransmitted or low-amplitude peristaltic contractions in more than

30% of wet swallows, decreased LES tone

- Treatment

- altered motility is irreversible

- best treatment is prevention: effective treatment of GERD

References

- Sabiston, 19th ed., pgs 1023 – 1032

- Cameron, 11th ed., pgs 39 – 43, 44 – 47

- UpToDate. Zenker’s Diverticulum. Schiff MD, Bradley. May 28, 2019. Pgs 1 – 22

- UpToDate. Achalasia: Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis. Spechler MD, Stuart. Feb 09, 2018. Pgs 1 – 22

- UpToDate. Overview of the Treatment of Achalasia. Spechler MD, Stuart. March 15, 2019. Pgs 1 – 17

- UpToDate. Major Disorders of Esophageal Hyperperistalsis: Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Castell MD, Donald. July 17, 2019. Pgs 1 – 21