Barrett’s Esophagus

- Pathophysiology

- intestinal columnar epithelium replaces the stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus

- chronic reflux injures the squamous epithelium and promotes repair through columnar metaplasia

- represents end-stage GERD

- continued reflux of acid (and bile) results in progression to low-grade and then high-grade dysplasia

- the chance of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma is 0.25% per year in patients without dysplasia,

and 4% - 8% per year in patients with high-grade dysplasia

- overall, 10% of patients with GERD develop Barrett’s esophagus

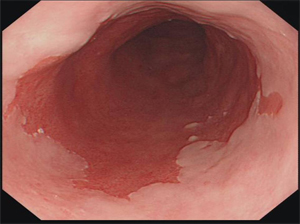

- Diagnosis

- made by endoscopy and pathology

- any length of endoscopically visible columnar epithelium above the GEJ that is confirmed histologically

to be within the esophagus is defined as Barrett’s esophagus

- Treatment of Nondysplastic Barrett’s Esophagus

- Medical Management

- treatment goal is to control GERD effectively

- PPIs are the first-line treatment

- annual surveillance endoscopy is usually recommended, but there is little evidence that it is beneficial

- Antireflux Surgery

- effective treatment for most patients with GERD and BE

- may produce higher rates of BE regression than medical therapy

- however, the long-term effects in preventing esophageal adenocarcinoma are controversial

- Endoscopic Therapies

- radiofrequency ablation and photodynamic therapy can eradicate BE cells and promote reversion back

to squamous epithelium

- no data to suggest that endoscopic ablative therapies reduce cancer risk or are more cost effective

than periodic long-term endoscopic surveillance

- Treatment of Dysplastic Barrett’s Esophagus

- Low-Grade Dysplasia

- medical therapy or antireflux surgery are effective treatment options for GERD

- endoscopic management (ablation or resection) is usually recommended for dysplasia,

but surveillance is another option

- if endoscopic surveillance is chosen, then it should be repeated every 6 – 12 months, with 4-quadrant biopsies

taken at 1 cm intervals

- High-Grade Dysplasia

- Endoscopic Eradication

- obvious mucosal abnormalities should be excised with endoscopic resection

- radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is then used to ablate the remaining metaplastic epithelium

- Esophagectomy

- most patients with high-grade dysplasia are now treated endoscopically

- transhiatal esophagectomy is the most common surgical procedure chosen

- minimally invasive approaches, and vagal-sparing techniques, are becoming more common

- Intramucosal Carcinoma

- endoscopic resection allows for histologic evaluation

- if there is no invasion of the submucosa, then endoscopic therapy is usually the preferred approach

- submucosal invasion will require esophagectomy

Esophageal Carcinoma

- Epidemiology

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- accounts for the great majority of cases worldwide

- very high incidence in Northern Iran and certain areas of South Africa, China, and Kazakhstan

- etiologic agents include additives to local foodstuffs (nitroso compounds) and ingestion of hot liquids

- in western countries, smoking and alcohol abuse are strongly linked

- premalignant conditions include achalasia, caustic esophageal burns (lye), and radiation esophagitis

- typically found in the upper and middle thirds of the esophagus

- Adenocarcinoma

- once rare, but is now the fastest growing cancer in the United States

- GERD and obesity are felt to play major etiologic roles

- now accounts for 60% - 70% of esophageal cancers in the U.S.

- originates in metaplastic columnar-lined epithelium (Barrett’s Esophagus) which occurs in 10% of patients

with GERD

- Barrett’s esophagus is associated with a 30 - 40X increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma

- Clinical Manifestations

- early-stage tumors may be asymptomatic and are usually found on routine endoscopic surveillance for

Barrett’s esophagus

- dysphagia and weight loss are the most common symptoms, and indicate advanced disease

- odynophagia may also be present

- extension of the tumor into the tracheobronchial tree can result in a tracheoesophageal fistula,

with symptoms of choking, coughing, and aspiration pneumonia

- paralysis of a recurrent laryngeal may occur as a result of local invasion

- Diagnosis and Staging

- Esophagram

- recommended for any patient presenting with dysphagia

- provides an overview of anatomy and function

- can distinguish between extrinsic and intrinsic compression

- classic finding of cancer is an apple core lesion

- Endoscopy

- allows biopsy of tumors

- can determine the distance of the tumor from the incisors and GEJ

- can assess for gastric cardia involvement and the suitability of the stomach as a replacement conduit

- CT Scan

- useful to evaluate the extent of the tumor and its relationships with surrounding structures,

regional nodal status, and metastatic disease to the liver and lungs

- only 57% accurate for T staging, 74% for N staging, and 83% for M staging

- PET-CT Scan

- probably the single best systemic staging tool

- overall accuracy for staging regional nodes and presence of distant disease is higher than CT scanning

- Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

- can determine the depth and length of the tumor, status of regional nodes

- EUS-FNA provides the most accurate nodal staging information

- overall T-stage accuracy is 85%, but is more accurate for increasing T stage

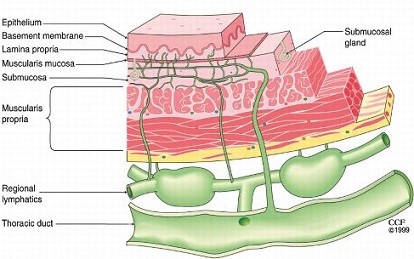

- Endoscopic Mucosal Resection

- for early-stage tumors, allows for accurate histologic distinction between mucosal (T1a) and

submucosal (T1b) tumors

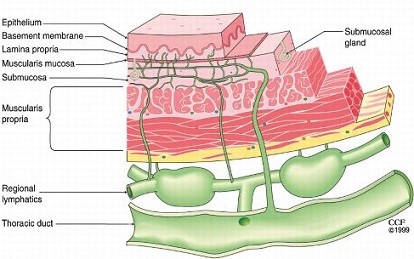

- since esophageal lymphatics are in the submucosa, T1a tumors can be treated endoscopically,

while T1b tumors require surgical resection

- Other Staging Tools

- bronchoscopy is used to rule out tracheal invasion or tracheoesophageal fistula in symptomatic patients

- mediastinoscopy may be used to biopsy suspicious nodes not amenable to EUS-FNA

- laparoscopy or thoracoscopy may be used to evaluate possible metastatic lesions in selected patients

- Cancer-Related Biomarkers

- beginning to find a role in esophageal cancer

- HER2 overexpression correlates with cancer progression and may be amenable to treatment with trastuzumab

- Staging

- precise staging allows for the most appropriate treatment

- tumor depth (T stage) directly relates to lymph node involvement

- T1a and superficial T1b tumors rarely metastasize to regional nodes

- deep T1b tumors (>50% of the submucosa invaded) are metastatic to regional nodes ~ 40% of the time

- T2 tumors involve the muscularis propria

- T3 tumors involve the adventitia

- T4 tumors locally invade other mediastinal structures

- Anatomy

- Arterial Supply

- segmental

- cervical esophagus receives its blood supply from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries

- thoracic esophagus receives blood from 4 to 6 esophageal aortic arteries, as well as from

branches of the bronchial and intercostal arteries

- abdominal esophagus receives blood from the left gastric artery and inferior phrenic arteries

- Venous Drainage

- is first into the submucosal venous plexus and then into the inferior thyroid vein (cervical esophagus);

bronchial, azygos, and hemiazygos veins (thoracic esophagus); and the coronary vein (abdominal esophagus)

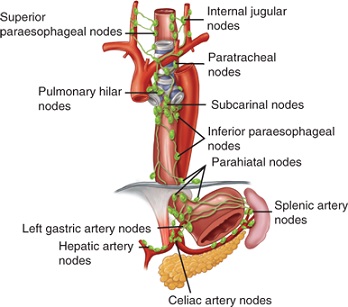

- Lymphatic Drainage

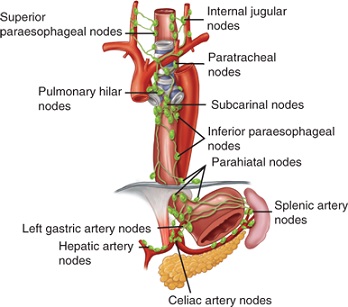

- esophagus has an extensive lymphatic drainage

- lymphatics are located primarily in the submucosa

- lymph flow is in the longitudinal direction, which facilitates spread along the esophageal wall

- lymph flow in the upper 2/3 of the esophagus is upwards (internal jugular nodes, paratracheal and

mediastinal nodes)

- lymph flow in the lower 1/3 of the esophagus is downwards (inferior paraesophageal nodes, left gastric nodes,

celiac artery nodes)

- Treatment

- Management Considerations

- Histology

- squamous cell cancer (SCC) is more responsive to chemoradiation than adenocarcinoma

- SCCs are more likely to have a complete clinical response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation,

making the need for surgical intervention uncertain

- Tumor Depth

- tumors confined to the mucosa (T1a) can be treated with endoscopic mucosal resection

- T2, T3 tumors should probably receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation

- Regional Nodal Status

- patients with known nodal disease, or those at high risk because of tumor depth, should probably

receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation

- Systemic Disease

- require definitive chemoradiation

- if totally obstructed, can consider a palliative resection if life expectancy is reasonable

- Patient Condition

- age, comorbidities, nutritional status affect the ability of patients to tolerate treatment

- most patients need preoperative pulmonary function and cardiac stress testing

- greater than a 10% weight loss or albumen level < 3.4 are associated with increased surgical complications

- nutritional status can be improved with an esophageal stent or feeding jejunostomy tube

- Neoadjuvant Treatment

- should be considered for all tumors at high risk for nodal metastasis (deeper than deep T1b)

- near consensus that surgery alone is inadequate for regionally advanced cancers

- concurrent chemoradiation is better than sequential chemotherapy and radiation

- one unanswered question is whether to proceed with an esophagectomy in a patient who has had a complete

clinical response to chemoradiation

- Surgical Resection

- Transhiatal Esophagectomy (THE)

- performed through an upper midline abdominal incision and a cervical incision, avoiding

a thoracotomy

- entire thoracic esophagus is resected

- stomach is used as the replacement organ in most cases

- the anastomosis is placed in the neck, avoiding the complications of an intrathoracic leak and

gastroesophageal reflux

- a pyloromyotomy and feeding jejunostomy are performed routinely

- this operation has been criticized as violating oncologic surgical principles by omitting a

formal lymph node dissection in potentially curable patients

- a laparoscopic procedure is now being done in some centers, and may be associated with lower complication

rates and shorter hospital stays

- Indications and Contraindications

- excellent palliative procedure

- many surgeons use this operation for ‘curative’ resections

- contraindications include tracheobronchial invasion and fixation to surrounding structures

- lowest mortality and major morbidity rates of all the esophageal resections

- Preoperative Considerations

- if the stomach is not available as an esophageal replacement because of previous gastric surgery,

then a barium enema of the colon is necessary to assess the suitability of the colon as the replacement organ

- Operative Considerations

- must preserve the right gastroepiploic vessels

- preserve the spleen

- pyloromyotomy and feeding jejunostomy are routine

- in the neck, the recurrent laryngeal nerves must be protected

- must assess the mobility of the tumor before proceeding with the thoracic phase of the

procedure

- much of the ‘blunt’, ‘blind’ thoracic phase of the procedure may be done sharply and

under direct vision by inserting long, narrow retractors through the esophageal hiatus

- mediastinal dissection must be kept close to the esophageal wall

- as the stomach is brought up into the neck, care must be taken not to twist the stomach in

the posterior mediastinum

- Complications

- intraoperative complications include pneumothorax, hemorrhage, and a tracheal tear

- postoperative complications include hoarseness, anastomotic leak or stricture, chylothorax,

and pleural effusion

- En Bloc Esophagogastrectomy

- requires 3 incisions: right posterolateral thoracotomy, upper midline abdominal incision,

left cervical incision

- gastrointestinal continuity is usually restored with the stomach

- radical thoracic and abdominal lymphadenectomies are performed

- some studies claim significantly better survival rates for early cancers than with transhiatal

esophagectomy

- has the highest mortality and morbidity rate of all the esophageal resections

- entire esophagus is resected, thereby eradicating submucosal spread

- avoids an intrathoracic anastomosis

- Left Thoracoabdominal Approach

- used for lesions in the distal esophagus and cardia

- distal esophagus, proximal stomach, and adjacent lymph node basins are resected

- a pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy is required for gastric drainage

- an intrathoracic anastomotic leak is the most feared and lethal complication

- intrathoracic anastomoses are invariably associated with reflux

- obtaining negative margins is difficult since esophageal carcinoma spreads extensively in the

submucosal plane

- there are increased respiratory complications from a combined thoracic and abdominal operation

- Ivor-Lewis Esophagogastrectomy

- combines right thoracotomy and abdominal incisions

- used primarily for lesions in the middle third of the esophagus

- has all the drawbacks of a transthoracic esophagectomy

- leak rates are low, but since they occur in the chest, they can be difficult to control

- often done now with a minimally invasive approach (thoracoscopic/laparoscopic)

- Vagal-Sparing Esophagectomy

- similar to THE

- vagal nerves are preserved by stripping the esophagus away from the nerves

- highly selective vagotomy is performed, so a pyloroplasty is not necessary

- advocated for use in intramucosal tumors

- Palliative Therapy

- ~50% of patients with esophageal carcinoma have local tumor invasion or distant metastases,

precluding cure

- primary goal is relief of dysphagia by reestablishing an esophageal lumen

- combination chemotherapy and radiation does not improve survival but can improve local control

- photodynamic therapy, endoscopic laser therapy, and esophageal stenting can all play roles in

palliating dysphagia

Benign Esophageal Tumors

- Leiomyomas

- now classified as GIST tumors (c-KIT-positive); true leiomyomas are rare

- dysphagia and pain are the most common symptoms

- have a distinctive appearance on barium swallow: smooth, concave defect with intact mucosa and sharp borders

- esophagoscopy should be done to rule out carcinoma, but if a leiomyoma is suspected it should not be biopsied

(scarring at the biopsy site complicates the extramucosal resection of the mass)

- asymptomatic incidentally found small tumors may be safely followed with periodic barium swallows

- symptomatic or large tumors should be removed by enucleation

References

- Sabiston, 19th ed., pgs 1047 – 1065

- Cameron, 11th ed., pgs 47 – 54, 54 – 58

- UpToDate. Barrett’s Esophagus: Surveillance and Management. Spechler MD, Stuart. Oct 15, 2018. Pgs 1 – 25

- UpToDate. Clinical Manifestations, diagnosis, and Staging of Esophageal Cancers. Saltzman MD, John, Gibson MD, Michael. Oct 22, 2018. Pgs 1 – 38

- UpToDate. Surgical Management of Resectable Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers. Swanson MD, Scott. Feb 07, 2019. Pgs 1 – 51