Gallstones and Cholecystitis

Gallstones

- Pathogenesis

- Cholesterol Stones

- most common type of gallstone in the West

- cholesterol is soluble in bile because it is packaged within bile salt-lecithin micelles

- when the relative amounts of cholesterol, bile salts, and lecithin are insufficient to package

all the cholesterol in micelles, then the bile is supersaturated with cholesterol and

precipitation of cholesterol crystals can occur

- nucleation is the process by which cholesterol crystals aggregate to form stones

- nucleating agents include bacteria, cellular debris, gallbladder mucus, calcium salts

- stasis of bile has also been implicated in stone formation

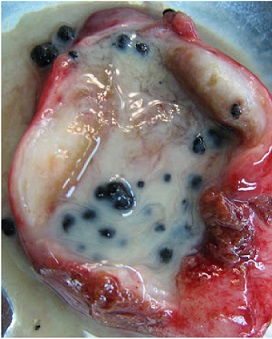

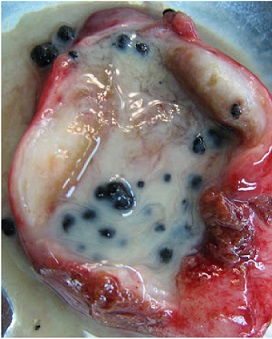

- Pigment Stones

- 2 types: black pigment stones and brown calcium bilirubinate stones

- Black Stones

- associated with cirrhosis and hemolytic conditions (sickle cell, thalassemia,

hereditary spherocytosis)

- bile contains an excess of unconjugated bilirubin

- Brown Stones

- soft, earthy in consistency

- much more common in Asia

- found almost exclusively in the bile ducts

- form in circumstances that predispose to bactobilia and infection

(biliary-enteric anastomosis, strictures, Caroli’s disease)

Clinical Syndromes

- Asymptomatic Gallstones

- Natural History of Gallstones

- 25 million people in the U.S. have gallstones

- up to 25% of women and 12% of men over 60 have gallstones

- only 20% of people with gallstones develop biliary symptoms during their lifetime

- symptoms requiring cholecystectomy develop in ~ 1% to 2% of asymptomatic patients per year

- risk of observation for most patients, even diabetics, with asymptomatic gallstones is less than or equal

to the risk of operation

- Asymptomatic Gallstones and Cancer Risk

- Porcelain Gallbladder

- results from chronic inflammation

- traditionally, most patients have been recommended to have a prophylactic cholecystectomy because of

the presumed high risk of developing gallbladder cancer (60%)

- more recent data suggests that the incidence is much lower (6%)

- younger, good-risk patients should probably have a cholecystectomy

- Gallbladder Polyps

- patients with large (>10mm), sessile gallbladder polyps should have prophylactic cholecystectomy

because of the higher risk of developing cancer

- Endemic Populations

- gallstones are almost always present in patients with gallbladder cancer

- Native American women have a very high incidence of gallstones and gallbladder

cancer and likely benefit from a prophylactic cholecystectomy

- Large Gallstones

- patients with stones > 3 cm have been reported to have a ten times greater cancer risk

- it is unclear if this population should be offered prophylactic cholecystectomy

- Incidental Cholecystectomy During Abdominal Operations

- very little data available to guide surgeons on how to manage incidentally found gallstones

at the time of abdominal operation

- when open abdominal surgery was the norm, incidental cholecystectomy was common, presumably

to avoid the morbidity of a later open cholecystectomy

- ultimately, it is up to the surgeon’s judgment whether to proceed with incidental cholecystectomy

- Special Populations to Consider

- Diabetics

- traditional teaching was that diabetics, because of autonomic neuropathy, were more

likely to present with advanced disease (acute cholecystitis, gangrene,

emphysematous cholecystitis)

- subsequent evidence does not support that diabetes is an independent risk factor for

worse outcomes

- prophylactic cholecystectomy for asymptomatic gallstones in diabetics is no longer

recommended

- incidental cholecystectomy at the time of laparotomy is a matter of surgical judgment

- Bariatric Surgery

- rapid weight loss after bariatric surgery results in increased gallstone formation secondary

to increased cholesterol secretion in bile

- altered anatomy after Roux-en-Y bypass can preclude endoscopic management of common duct

stones

- multiple management strategies exist for bariatric patients with asymptomatic

gallstones, with none being clearly more advantageous:

- prophylactic cholecystectomy only if gallstones are present

- postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid for 6 months to dissolve gallstones or to

prevent their formation

- expectant management

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy in bariatric patients is more difficult because of the size and

weight of the liver

- Sickle Cell Disease

- hemolysis results in the formation of pigment stones from excessive bilirubin excretion into bile

- majority of sickle cell patients have gallstones by age 22, and 75% of these patients

will develop symptomatic disease

- differentiating between biliary symptoms and a sickle cell crisis can be difficult

- prophylactic cholecystectomy is usually recommended in this patient population

- to avoid precipitating a crisis during surgery, careful attention must be made to

hemoglobin optimization, adequate hydration and oxygenation, and good pain control

- patients with other hemolytic anemias (spherocytosis, thalassemia) are usually advised to have a

cholecystectomy only after biliary symptoms develop

- Transplant Patients

- chronic immunosuppression is associated with a delayed presentation and diagnosis of

surgical diseases

- cyclosporine and tacrolimus are cholelithogenic

- for these reasons, prophylactic cholecystectomy historically was recommended prior to

transplant or following transplant if asymptomatic gallstones developed

- modern data now convincingly supports expectant management in kidney or pancreas

transplant patients with asymptomatic gallstones

- however, evidence strongly supports posttransplant prophylactic cholecystectomy for

asymptomatic gallstones in heart and lung transplant patients

- Biliary Colic

- often referred to as symptomatic cholelithiasis or chronic cholecystitis

- characterized by recurrent episodes of moderate to severe right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that

may radiate to the right scapula or straight through to the back

- atypical presentations are common as well: mild pain, pain not associated with meals, left upper

quadrant or right lower quadrant pain, bloating and belching

- symptoms may also mimic cardiac symptoms

- pain results from temporary obstruction of the cystic duct by a gallstone

- nausea and vomiting may occur during the attack

- the attacks may be triggered by eating, especially fatty foods, and usually last from 30 minutes

to several hours

- the interval between attacks is highly variable: they may be frequent or months or years apart

- diagnosis is made by an ultrasound showing gallstones

- elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice

- Acute Cholecystitis

- Acute Calculous Cholecystitis

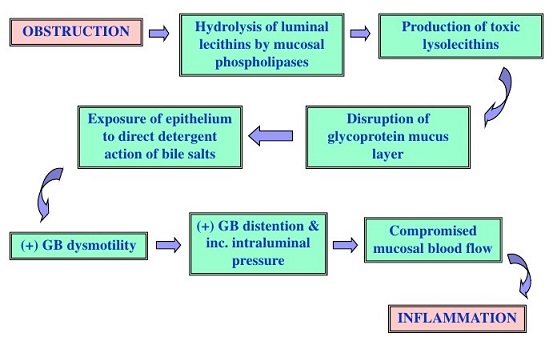

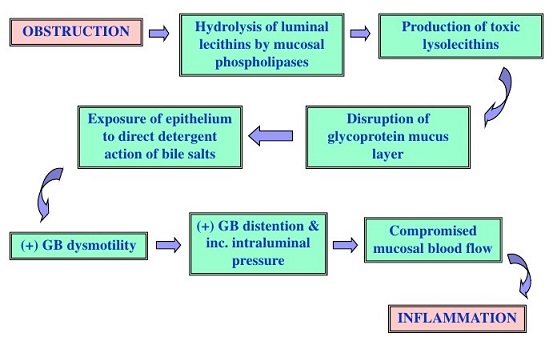

- Pathogenesis

- cystic duct obstruction leads to gallbladder wall distention, inflammation, edema,

ischemia and necrosis

- inflammation is initially sterile, but secondary bacterial infection may occur since

bile cultures are positive in 50% of cases

- acute cholecystitis is not the inevitable outcome of cystic duct obstruction

(e.g. hydrops) and so obstruction and some other factor is necessary for the development

of acute cholecystitis

- Clinical Manifestations

- usually occurs in patients with a previous history of symptomatic cholelithiasis

- often occurs after the ingestion of a heavy or fatty meal

- patients have moderate to severe right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that may

radiate to the scapula

- unlike in biliary colic, the pain persists and may last for several days

- nausea and vomiting occur in 60% to 70%

- physical findings include fever in 80%, right upper quadrant tenderness

- Murphy’s sign, inspiratory arrest during deep palpation of the right upper quadrant,

is pathognomonic when present

- majority of patients have an elevated WBC

- mild elevation of LFTs is common as well

- Imaging Studies

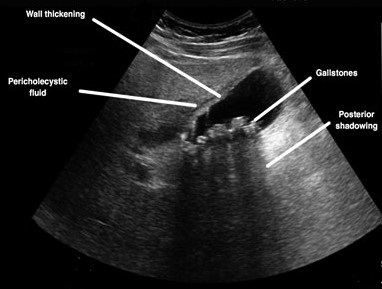

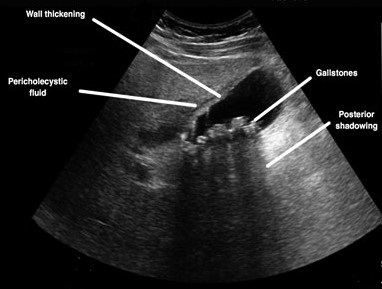

- Ultrasound

- accurately detects gallstones and is the diagnostic test of choice in straightforward cases

- may reveal a thickened gallbladder wall or pericholecystic fluid

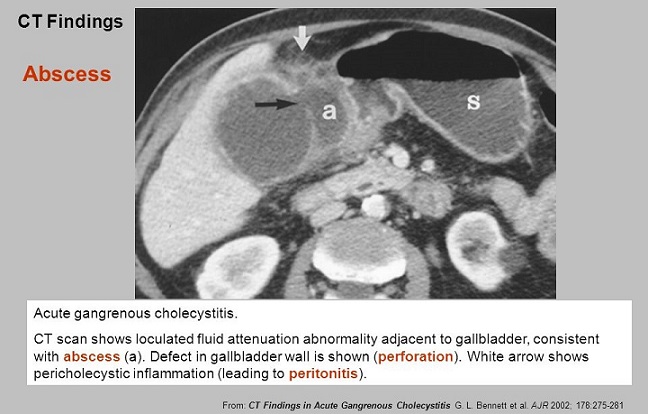

- CT Scan

- does not detect gallstones as accurately as ultrasound

- more sensitive than ultrasound in detecting pericholecystic fluid, inflammation,

and gallbladder wall thickening

- more versatile than ultrasound in diagnosing other pathologies in the differential diagnosis

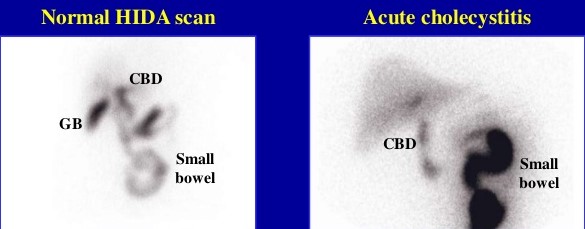

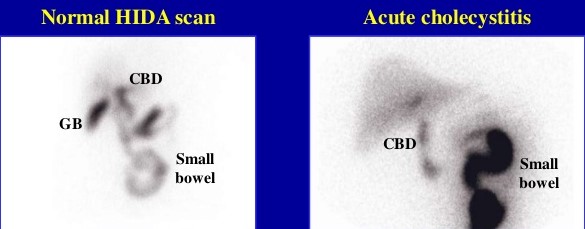

- HIDA Scan

- most specific test for acute cholecystitis

- non-filling of the gallbladder, presumably because of cystic duct obstruction,

indicates acute cholecystitis

- generally reserved for atypical cases

- does not provide useful information regarding other possible diagnoses

- Complications

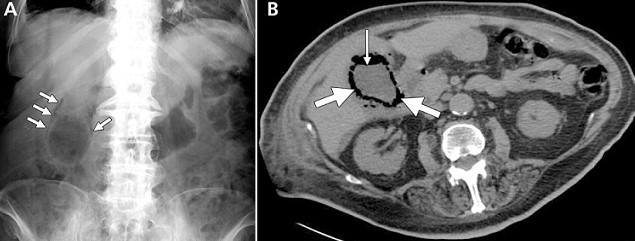

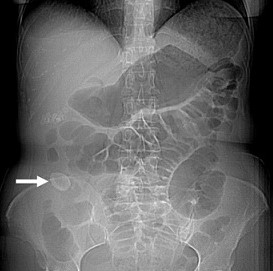

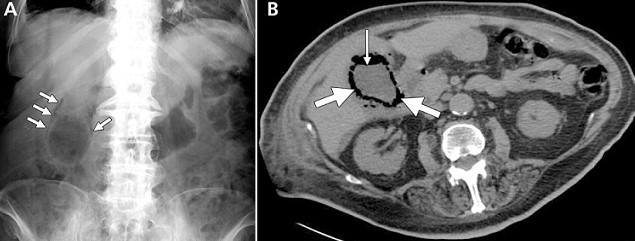

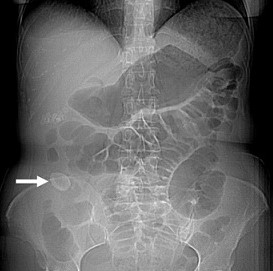

- Emphysematous Cholecystitis

- caused by gas-forming organisms (clostridia, E. coli, Klebsiella)

- more common in diabetics

- patients are often septic

- plain x-rays will suggest the presence of gas in the gallbladder wall or lumen

- if the patient is too unstable to undergo cholecystectomy, then a cholecystostomy

should be placed

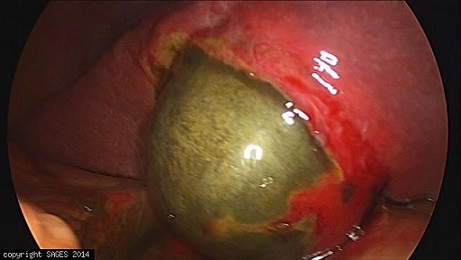

- Empyema

- pus within the gallbladder

- equivalent to an intra-abdominal abscess

- treatment is cholecystectomy or cholecystostomy

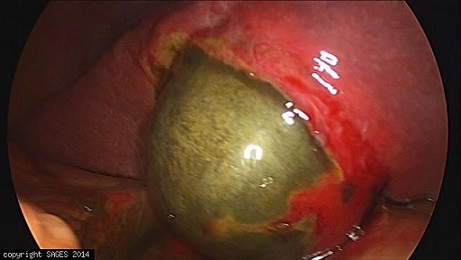

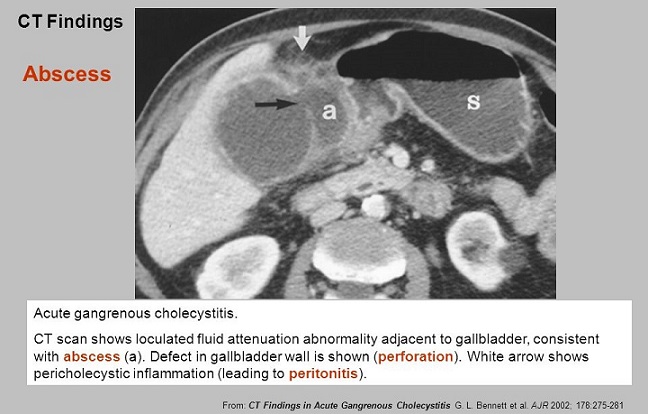

- Gangrenous Cholecysitis

- free perforation occurs when a gangrenous area becomes necrotic and bile leaks

into the peritoneal cavity, resulting in generalized peritonitis

- mortality is ~ 20%

- Pericholecystic Abscess

- results from a gallbladder perforation that is walled off by omentum or

adjacent organs

- Fistulas

- occurs when the gallbladder becomes attached to a portion of the

gastrointestinal tract and perforates into it

- duodenum and colon are the most common sites; stomach and jejunum are rare

- a large gallstone may become lodged in the terminal ileum causing a small bowel

obstruction (gallstone ileus)

- the obstructing stone must be removed via an enterotomy

- in sick patients alleviating the obstruction is sufficient

- in healthier patients, can consider cholecystectomy/fistula repair in the same

setting if the inflammatory reaction in the right upper quadrant is not

too severe

- Treatment

- Cholecystectomy

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred operation and ideally

should be done within 72 hours of admission

- conversion rate to open cholecystectomy may be as high as 20% in acute cases

- in cases with severe inflammation, a partial cholecystectomy may be necessary

to avoid injury to the common bile duct

- if the back wall of the gallbladder is fused to the liver, then it can be left

in place and the mucosa cauterized to prevent a mucocele

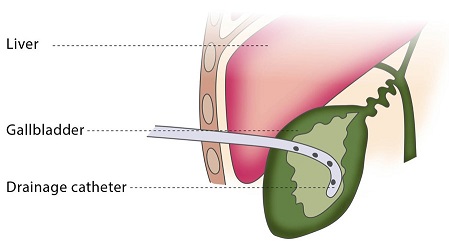

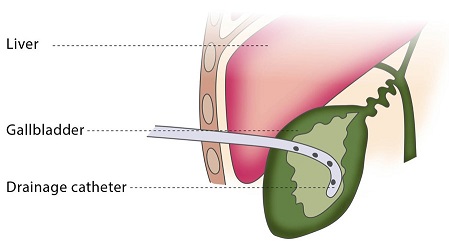

- Cholecystostomy

- indicated in the unstable patient who will not tolerate a general anesthetic

- may be performed percutaneously in the radiology suite or surgically under

local anesthetic

- patients must be observed carefully, since gangrenous areas can perforate

- additional complications include failure of resolution or progression of cholecystitis,

sepsis, and tube dislodgement

- elective cholecystectomy should follow in 3 months after medical optimization

- Antibiotics

- IV antibiotics active against the common biliary pathogens (E. coli, Klebsiella,

Streptococcus faecalis, Clostridia, Proteus) should be administered immediately

- for patients with severe comorbidities and mild acute cholecystitis, a 7 – 14 day course

of antibiotics may be sufficient treatment

- acute cholecystitis in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy is often treated medically

- Acalculous Cholecystitis

- 5% to 10% of cases of acute cholecystitis

- more common in males

- usually occurs in conjunction with another serious illness such as major trauma, sepsis, or burns

- Etiology

- probably multifactorial

- bile stasis may lead to the formation of a viscus sludge, which may obstruct the

cystic duct

- stasis of bile may also lead to bacterial colonization

- ischemia may result in mucosal sloughing, which would then give bile acids, which are

toxic to tissues, access to the gallbladder wall

- Diagnosis

- may be delayed because of other concomitant problems

- symptoms and signs are similar to acute calculous cholecystitis, except that they are

often masked by the underlying condition, narcotic administration, or decreased level

of consciousness

- ultrasound or CT scan findings include a distended gallbladder with a thickened wall, sludge,

pericholecystic fluid

- HIDA scan will show nonvisualization of the gallbladder but its accuracy is not as high

as in calculous cholecystitis (viscus bile may prevent the radionuclide from entering

the otherwise normal gallbladder)

- Treatment

- emergent cholecystectomy is indicated, because of the high risk of gangrene and

perforation

- percutaneous cholecystostomy may be performed in extremely high-risk patients who will

not tolerate surgery

- Biliary Dyskinesia

- presents with typical biliary-like symptoms but no discernible gallstones or sludge

- diagnosis is made by a cholecystokinin HIDA scan that shows a low gallbladder ejection fraction (< 35%)

- treatment is elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with 85% of patients having resolution of symptoms

- pathology typically reveals chronic acalculous cholecystitis

References

- Schwartz, 10th ed., pgs 1316 – 1321, 1327 – 1330

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 1482 - 1497

- Cameron, 11th ed., pgs 383 -387, 387 - 390

- Cameron, 13th ed., pgs 437 – 440, 441 – 444, 444 - 452