Ventral and Incisional Hernias

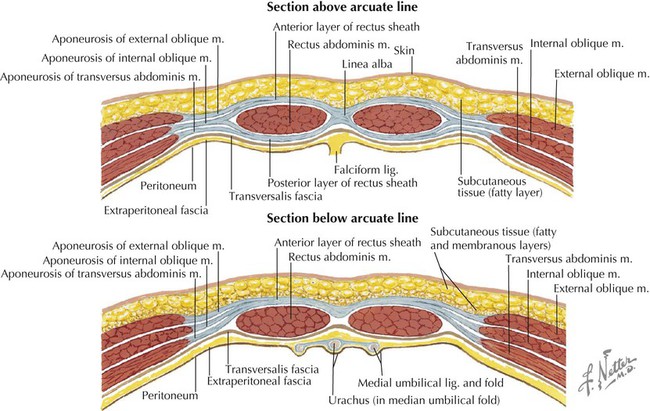

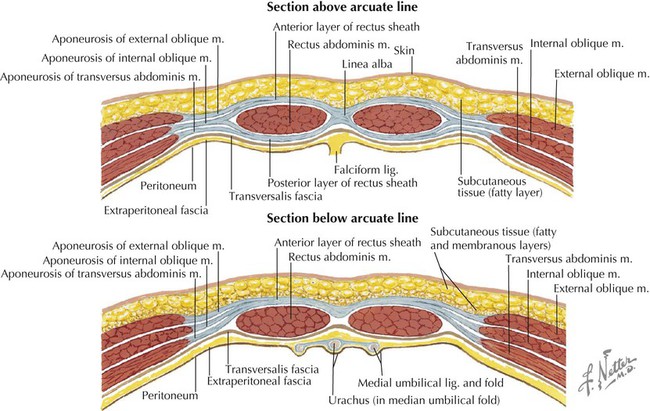

Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall

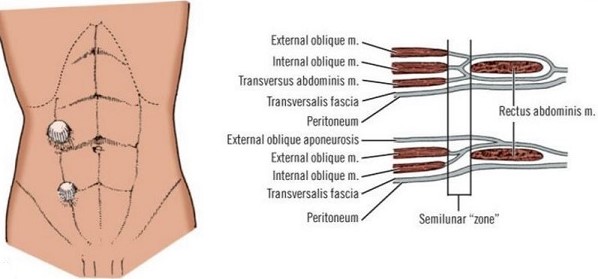

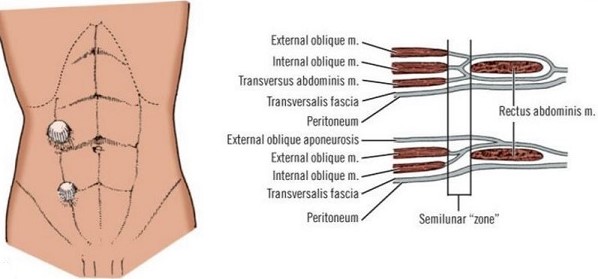

- Muscle Layers

- Rectus Muscles

- longitudinally paired muscles encased within fascial sheaths

- the linea alba is where the anterior and posterior fascial sheaths fuse at the midline

- the arcuate line lies at roughly the level of the anterior superior iliac spine

- above the arcuate line, the posterior rectus sheath is made up of the internal lamina of the internal

oblique fascia and the transverse abdominis fascia

- below the arcuate line, the posterior rectus sheath is absent

- laterally, the rectus sheath fuses with the fascia of the lateral muscles to form the semilunar line

- Lateral Muscles

- 3 muscles oriented obliquely to each other

- the fascia of these layers combine to form the semilunar line, which then contributes to the

anterior and posterior rectus sheaths

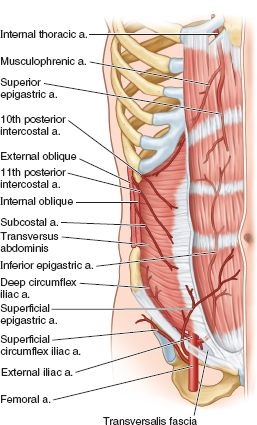

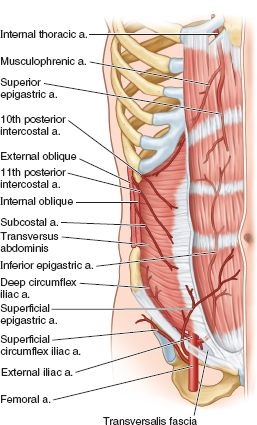

- Blood Supply

- primarily originates from the superior and inferior epigastric arteries

- inferior epigastric artery originates from the external iliac artery

- superior epigastric artery originates from the internal thoracic artery

- a collateral network of intercostal, lumbar, and deep circumflex iliac arteries also

contributes to abdominal wall blood supply

Ventral Hernias

- Umbilical Hernias

- Etiology

- Children

- congenital in origin

- most close spontaneously by age 2

- 8X more common in African-Americans

- Adults

- acquired condition

- more common in women

- may result from conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure: pregnancy, obesity,

ascites, constipation, chronic cough

- Management

- small, asymptomatic hernias do not need to be repaired

- all symptomatic hernias should be repaired

- defects < 3 cm in size can often be close primarily after excising the hernia sac

- larger defects are closed with a mesh patch placed in an inlay, onlay, or sublay position

- repairs may be done open or laparoscopically

- no universal consensus on the best method of repair

- Umbilical Hernia Repair in Cirrhotics

- umbilical hernias in patients with ascites will continue to enlarge

- skin breakdown with spontaneous rupture of the hernia can result in peritonitis and death

- cirrhotics are often hypoalbuminemic and coagulopathic, making them high-risk surgical candidates

- historically, elective repair was contraindicated because of the high morbidity and mortality rates

- with modern preoperative and intraoperative management, serious complication rates are < 10%,

making elective repair feasible for many patients

- Preoperative Preparation

- includes free water restriction, diuretics, and large volume paracenteses

(with infusion of albumin)

- some series report good results with perioperative placement of a temporary peritoneal dialysis catheter or

transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

- there is no current indication for placement of a perioperative peritoneovenous shunt

- Surgical Management

- use of synthetic mesh is not contraindicated, and is associated with lower recurrence

rates (3%) than primary repairs (15%)

- both onlay and retrorectus sublay repairs give equivalent results

- venous abdominal wall collaterals should not be ligated because this can cause hepatic

decompensation

- Epigastric Hernias

- Presentation

- more common in men

- located between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus

- usually are painful because they often contain incarcerated preperitoneal fat

- Management

- repair is indicated, since most are symptomatic

- small hernias can be closed primarily, but larger lesions will require mesh

- Diastasis Recti

- may be confused with an epigastric hernia

- is an area of weakness that results from the stretching of the linea alba

- presents as a diffuse midline bulge, but no true hernia defect is present

- abdominal US or CT scan can confirm the diagnosis

- does not require repair

- Incisional Hernias

- Etiology

- result from excessive tension and inadequate healing of an incision

- wound infections and hematomas greatly increase the risk of incisional hernias

- corticosteroids and chemotherapy drugs contribute to poor wound healing

- other risk factors include obesity, older age, malnutrition, ascites, diabetes,

chronic pulmonary disease

- Pathophysiology

- pain, bowel obstruction, incarceration, and strangulation may result

- large hernias may result in loss of abdominal domain

- Nonoperative Management

- preferred option for asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients

- symptomatic patients with modifiable risk factors should also initially be managed nonoperatively

- patients with a BMI > 35 should be put on a weight loss program or may need to consider bariatric surgery

before proceeding with hernia surgery

- patients will also need to quit smoking and get their diabetes under good control before considering

elective surgery

- Operative Repair

- almost all will require a mesh repair

- choice of mesh will depend on whether the mesh will be in direct contact with the bowel, and the

presence or risk of infection

- the ideal mesh has yet to be developed

- Types of Mesh

- Polypropylene Mesh (Marlex)

- macroporous mesh that allows ingrowth of fibroblasts and incorporation into the

surrounding fascia

- should not be placed in an intraperitoneal position, since bowel will adhere to it,

resulting in a high rate of enterocutaneous fistulas

- PTFE Mesh (Gortex)

- impermeable to fluid

- not incorporated into native tissue

- resists adhesion formation

- Composite Mesh

- consists of a PTFE surface and a polypropylene surface

- PTFE side is placed against the bowel, and the polypropylene side is placed superficially

and is incorporated into the native tissue

- since these materials have different rates of contraction, buckling of the mesh can occur,

with resulting exposure of the polypropylene surface to the bowel

- Biologic Mesh

- nonsynthetic, natural tissue mesh

- comes from human, bovine, or porcine sources

- composed of acellular collagen

- provides a framework for neovascularization and native collagen deposition

- typically used in infected or contaminated cases in which synthetic mesh is contraindicated

- functions best as a fascial reinforcement rather than as a bridge or interposition repair

- long-term durability of these products is unresolved

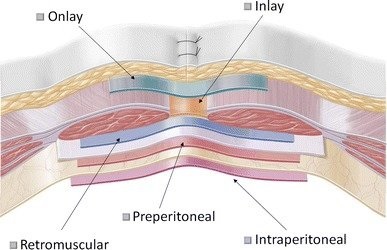

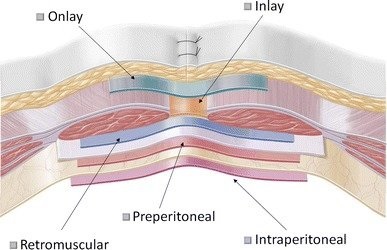

- Mesh Placement

- basic concept is to place a piece of mesh larger than the defect with a wide overlap

- Overlay Technique

- involves primary closure of the fascial defect (if possible), and placement of the mesh

over the anterior fascia

- major advantage is that the mesh is not in contact with the bowel

- major disadvantages include large subcutaneous flaps, increased seroma formation,

superficial location of the mesh with increased infection risk, and the

increased tension from the primary closure

- reported recurrence rate is ~28%

- Inlay Technique

- involves suturing the mesh to the fascial edges without overlap

- has the highest recurrence rate

- Sublay Technique

- mesh is widely placed below the fascia

- mesh can be placed preperitoneally or retromuscularly

- intra-abdominal pressure will help to hold the mesh in place

- lower recurrence rate and complication rate than the overlay or inlay techniques

- Intraperitoneal Mesh Placement

- laparoscopic repairs use intraperitoneal composite mesh placement secured with tacks or

mattress sutures

- one advantage is the ability to widely place the mesh around the hernia defect

(at least 4 cm)

- associated with fewer wound complications

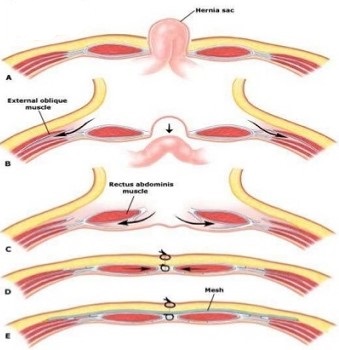

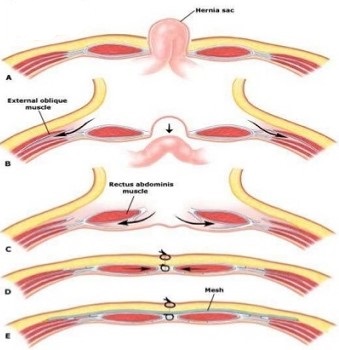

- Components Separation

- used to create an advancement flap of the rectus muscles towards the midline

- usually is augmented with mesh placed in an onlay or sublay position

- restores the linea alba, resulting in a more functional abdominal wall

- Anterior Component Separation

- large subcutaneous flaps are raised above the external oblique fascia

- bilateral longitudinal relaxing incisions are made in the external oblique fascia

2 cm lateral to the semilunar line

- extent of the relaxing incision is from the costal margin to the pubis

- the external oblique is bluntly dissected away from the internal oblique, facilitating

its advancement

- if necessary, additional release may be obtained by making a relaxing incision in the

posterior rectus sheath

- up to 20 cm of mobilization can be obtained with these techniques

- common complication is wound breakdown from devascularized skin flaps caused by the

extensive undermining required

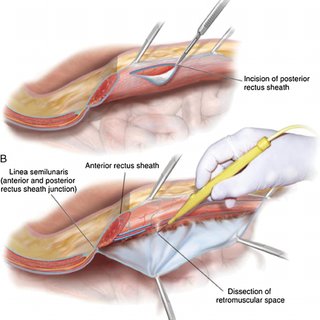

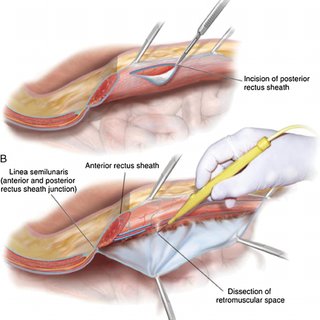

- Transversus Abdominis Release (TAR)

- TAR starts by entering the posterior rectus sheath and developing a retrorectus plane

- the lateral dissection is extended to 1 cm medial to the linea semilunaris preserving the

neurovascular bundles innervating the medial abdominal wall

- the transversus abdominis muscle fibers are identified and divided to enter a retromuscular

and preperitoneal plane

- the dissection is then continued laterally to the psoas muscle

- after bilateral TAR is completed, the posterior rectus sheath is closed in the midline to

fully isolate the visceral contents from prosthetic mesh placement

- closure of the posterior rectus sheath also creates a space for the placement of a large

piece of mesh in a sublay retromuscular position

- after mesh implantation, the rectus muscle and anterior rectus sheath are closed above

the mesh to restore the midline abdominal wall

- Complications

- Mesh Infections

- PTFE mesh will need to be removed

- Marlex mesh can sometimes be salvaged with wound debridement and conservative

excision of unincorporated mesh

- laparoscopic repairs are associated with a much lower incidence of wound complications

- Seromas

- in open repairs, drains are usually placed to obliterate the dead space caused by dissecting

out the hernia sac

- seromas commonly reform after the drains are removed

- drains are also a conduit for bacterial contamination of the mesh

- in laparoscopic repairs, since the hernia sac is not removed, seromas are inevitable

- wearing an abdominal binder 24 hours/day can minimize and prevent seroma formation

- Bowel Injury

- may occur during adhesiolysis

- management depends on the type of bowel injured (small bowel vs colon), and the amount of spillage

- options include aborting the repair, primary tissue repair, using a biologic mesh, or delayed repair

with synthetic mesh in 3 to 4 days

- the use of synthetic mesh in a grossly contaminated wound is contraindicated

- Risk Factors for Recurrence After Repair

- recurrence rates after incisional hernia repair may be as high as 30%

- hernia width and contamination are the 2 most significant risk factors for recurrence

- hernia length, hernia location (midline versus lateral), and significant comorbidities (e.g., obesity,

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, or smoking within 3 months of the operation) are

not as important for predicting recurrence

- Prevention of Incisional Hernias

- Laparotomy Closure Technique

- the technique and choice of suture material influences incisional hernia rates

- slowly (6–9 months) absorbable suture (polydioxanone, PDS) is preferred over rapidly (2–3 months)

absorbable suture (polyglactin, Vicryl)

- the rate of incisional hernias is lowest when small, closely spaced fascial bites are used

- 2 randomized trials using 2-0 polydioxanone and small, closely spaced fascial bites (5 mm deep

and 5 mm apart) demonstrated the lowest incisional hernia rate

- prophylactic onlay mesh reinforcement of elective midline laparotomy incisions reduces incisional

hernias but increases the rate of seromas and wound infections

- Parastomal Hernias

- Clinical Manifestations

- occurs in 50% of colostomies

- most are asymptomatic

- incarceration, bowel obstruction, or strangulation are rare

- routine repair is not recommended

- indications for repair include obstructive signs, difficulty applying an appliance, cosmesis

- Repair Techniques

- Primary Fascial Repair

- simplest option, but associated with the highest recurrence rate

- may be reinforced with mesh

- should only be used in patients who will not tolerate a laparotomy

- Stoma Relocation

- predisposes patient to another parastomal hernia in the future

- new stoma site may be reinforced with synthetic or biologic mesh

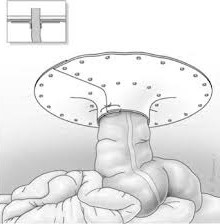

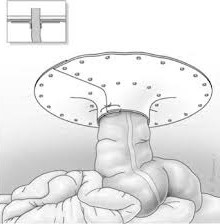

- Intraperitoneal Mesh Repair

- Keyhole Technique

- hernia is reduced and the defect closed primarily

- the site is then reinforced with a large piece of mesh which surrounds the ostomy

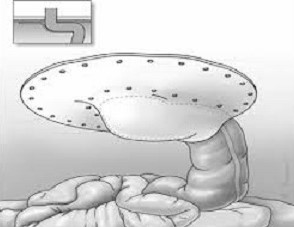

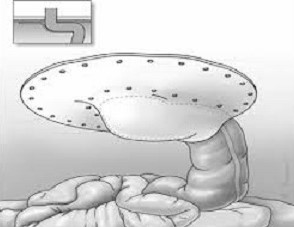

- Sugarbaker Procedure

- lateralizing the stoma redistributes the forces, minimizing hernia recurrence

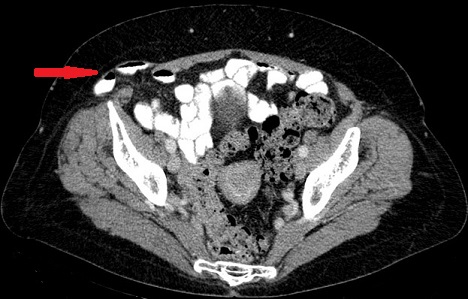

- Spigelian Hernias

- Anatomy

- defect in the semilunar line, usually below the arcuate line (where the posterior rectus fascia ends)

- may also result from surgical drains or laparoscopic ports

- hernia sac is usually below the external oblique fascia (interparietal)

- Clinical Presentation

- presents with localized pain but no bulge, because the hernia is below the intact external oblique fascia

- CT scan is usually required for the diagnosis

- should be repaired because of the high risk of incarceration

- Repair

- may be repaired open or laparoscopically

- in an open repair, the transversus abdominis and internal obliques muscles are repaired,

often without mesh

References

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 1106 – 1116

- Cameron, 13th ed., pgs 631 - 635, 635 - 644, 650 - 656

- Schwartz, 10th ed., pgs 1449 - 1456

- SESAP 17. American College of Surgeons. Alimentary Tract.