Medical Tests and Medical Studies

Medical Tests

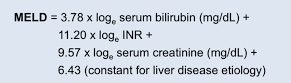

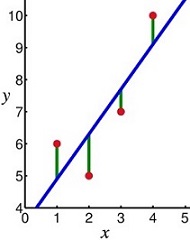

- Linear Regression

- linear approach to modeling the relationship between a dependent (response) variable (y) and

one or more explanatory (predictor) variables (x)

- simple linear regression involves only one predictor variable

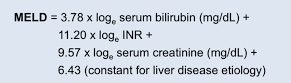

- multiple linear regression involves two or more predictor variables (MELD score):

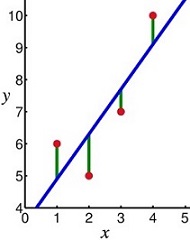

- basic idea is to find a line that best fits the data

- best fit line minimizes the differences in the ‘y’ direction

- linear regression line equation: y = bx + a

- a is the y intercept, and b is the slope

- the x variable is used to make predictions about the y variable

- Correlation Coefficient (R) and Coefficient of Determination (R2)

- R is the numerical measure of correlation between 2 continuous variables, with values ranging from +1

(strongest positive correlation) to -1 (strongest negative correlation)

- R2 is the proportion of the variance for a dependent variable that is explained by an

independent variable or multiple variables in a regression model

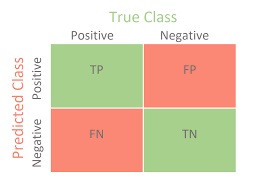

- Performance Metrics of Medical Tests

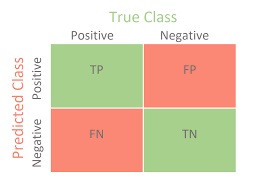

- Contingency Table

- displays the results of a test and the correctness of the classification

- TP: test correctly identifies the condition as present

- TN: test correctly identifies the condition as not being present

- FP: test incorrectly identifies the condition as present

- FN: test incorrectly identifies the disease as not being present

- Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity

- Accuracy

- TP + TN / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

- measures the percentage of all correct test results

- not often used in medicine because many conditions being tested for have a low

incidence (<1%)

- if these low incidence conditions are missed, it will not affect the accuracy of

the test much, but it can have devastating consequences to the patient

(failure to make an early diagnosis)

- Sensitivity

- true positive rate: percentage of patients who test positive who actually

have the condition

- TP / (TP + FN)

- the most important performance metric for medical testing, since a high value

means that few patients with the condition will be misdiagnosed as negative

- Specificity

- true negative rate: percentage of patients who test negative who do not

have the condition

- TN / (TN + FP)

- a low specificity rate means a higher number of false positive tests

- for medical testing, there is a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity

- a higher sensitivity rate (few false negatives) will result in a lower specificity rate

(more false positives)

- Predictive Value of a Test

- sensitivity tells us how often the test will be positive if the condition is present

- however, clinically, what we usually want to know is how often the condition is present

if the test is positive – this is known as the positive predictive value

- likewise, the negative predictive value is how often the condition is not present when the

test is negative

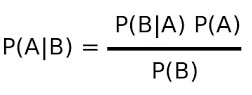

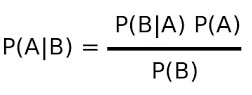

- to calculate the positive predictive value, we need to know the sensitivity of the test

(P(B|A)), the incidence of the disease in the population (P(A)), and the total number

of people who test positive (true positives + false positives (P(B)))

- Likelihood Ratio

- used to estimate the odds that a condition is present or absent

- not dependent on knowing the disease prevalence

- Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR)

- how much to increase the probability of having a disease, given a positive test

- probability that a person with the condition tests positive (true pos)

/ probability that a person without the condition tests positive (false pos)

- Positive LR = sensitivity / (1 – specificity)

- Negative Likelihood Ratio

- how much to decrease the probability of having a disease, given a negative result

- probability a person with the condition tests negative (false negative)

/ probability that a person without the condition tests negative (true negative)

- Negative LR = (1 – sensitivity) / specificity

Medical Studies

- Magnitude of Effect

- medical studies often aim to describe the relationship between a treatment (exposure) and outcome

- the magnitude of a treatment effect can be measured in both absolute and relative terms

- Absolute Measures of Effect

- Absolute Risk Reduction

- difference between the incidence of a disease/event in the control group and the

incidence of the same outcome in the treated group

- Number Needed to Treat (NNT)

- how many patients must be treated to see the effect of the treatment

- reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction

- the ideal NNT = 1

- provides valuable insight into the clinical relevance of the treatment effect

- Relative Measures of Effect

- Relative Risk

- calculates the ratio of incidence proportions between 2 different groups (treated + control)

- relative risk reduction can make treatments seem more effective than they are

- Odds Ratio (OR)

- represents the probability of an outcome

- odds that an outcome will occur given exposure to a variable of interest, compared to the odds of

the outcome occurring in absence of the exposure

- most commonly used in case-control studies

- an OR < 1 means that the risk of the outcome is lower in exposed individuals than in unexposed

individuals; an OR > 1 means that the odds are higher in exposed individuals

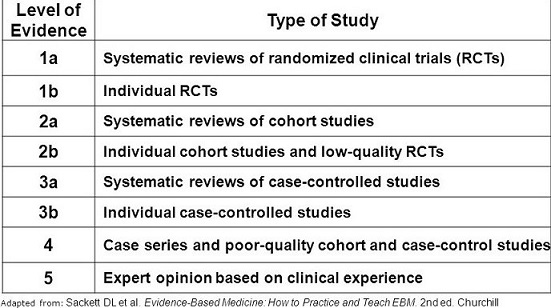

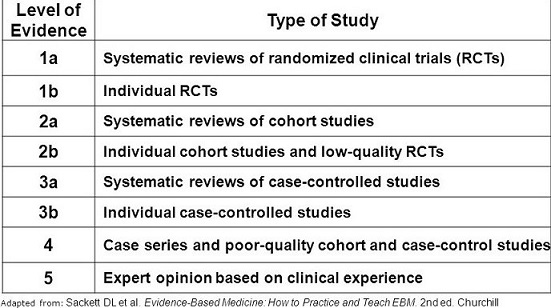

- Evidence-Based Medicine

- integration of the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values

- different types of medical studies provide different levels of research evidence

- Types Of Medical Studies

- Systematic Reviews

- summary of the medical literature that uses explicit and reproducible methods to

systematically search, critically appraise, and synthesize information on a

specific issue

- synthesize the results of multiple primary studies related to each other by using

strategies that reduce biases and random errors

- since no study, regardless of its type, should be interpreted in isolation,

a systematic review is generally considered the best form of evidence

- may or may not include a statistical synthesis called meta-analysis, depending on whether

the studies are similar enough so that combining their results is meaningful

- Cochrane reviews are the most well-known type of systematic reviews

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT)

- provide the highest level of evidence supporting causality

- primary advantage of RCTs is that confounding variables are distributed equally between

groups, as long as the number of study subjects is sufficiently large

- single-blind study is when the patients do not know which treatment they received,

and is intended to mitigate the placebo effect

- double-blind study is when neither the treating physician nor the patient knows which

treatment they received, and is intended to mitigate investigator bias

- in practice, blinding in surgery is rarely practical

- Intention to Treat Principle (ITT)

- outcome comparisons are based on the original randomization, not on the treatment

the patient actually received

- patients may crossover if they are not able to complete the intervention

- if the ITT principle is not followed, then the benefits of randomization may be

lost because an equal number of confounders across comparison groups cannot be

guaranteed

- Meta-Analyses

- considered a subset of systematic reviews

- many medical studies are underpowered to answer a particular research question and

results of multiple small studies may be conflicting

- meta-analysis is a statistical technique that pools similar studies in an attempt

to increase the statistical power of the analysis

- several small studies are combined to make one larger study – a study of studies

- it is important that the pooled studies be homogenous and evaluate similar end points and patient populations

- a failure to identify all the existing studies can lead to erroneous conclusions

- many relevant studies may not have been published if they did not reach the necessary statistical threshold

- now the most frequently cited form of medical research

- Cohort Studies and Case-Control Studies

- longitudinal, observational studies without randomization, making them vulnerable to

unpredictable confounding factors

- evaluate associations between diseases and exposures

- very common in medicine because many questions cannot be ethically answered by RCTs

- provide level 2 or 3 evidence

- Cohort Studies

- participants are followed over time to observe the incident rate of

disease or outcome in question

- may be prospective or retrospective in design

- no intervention or treatment is administered as part of the study

- no control group

- Nurses’ Health Study, Framingham Heart Study (1948) are ongoing examples

- Advantages

- can assess causality

- can examine multiple outcomes for a given causality

- can calculate relative risks or rates of disease in exposed and unexposed individuals

over time

- Disadvantages

- selection bias

- inefficient for rare outcomes, or outcomes that occur a long time after group assignment

- long duration of follow up is required, which is time consuming and expensive

- patients can be lost to follow up

- Case-Control Studies

- retrospective studies that start with the outcome of interest and work backward to the exposure

- patients with a disease are identified and compared with controls for exposure to a risk factor

- controls are from the same source population but without the outcome

- one famous example linked smoking to lung cancer in the 1950s

- Advantages

- useful for examining rare outcomes or outcomes with a long latency

- relatively quick and inexpensive

- can use existing records

- Disadvantages

- control group selection may be difficult

- can be difficult to validate information retrospectively

- susceptible to bias

- relative risk or incidence of disease cannot be calculated

- odds ratio must be used to provide an estimate of relative risk

- Cross-Sectional Study

- prevalence studies or censuses

- involve data collected at a single point in time

- cannot assess cause and effect (no temporality)

- mostly used for hypothesis generation instead of hypothesis testing

- one example of this type of study is to determine whether surgical patients are

receiving adequate VTE prophylaxis

- Case Reports and Case Series

- a case report highlights an unusual or unexpected event

- a case series demonstrates that the unusual event can occur more than once

- most useful for hypothesis generation

- an example is several reports of port site recurrence in the early days of

laparoscopic colon cancer resections

References

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 173 - 184

- UpToDate. Glossary of Common Biostatistical and Epidemiologic Terms. Peter A. L. Bonis, MD.

March 04, 2020. Pgs 1 – 24

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis: Understanding the Best Evidence in Primary Healthcare.

S. Gopalakrishnan and P. Ganeshkumar. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3894019/