Gastric Adenocarcinoma

- Epidemiology

- 50 years ago, gastric cancer accounted for 20% to 30% of all cancer deaths in the U.S.

- now it is a relatively rare disease in the United States (~ 27,500 new cases per year with ~ 11,000 deaths)

- the reason for this trend is unknown

- the decline has been in antral tumors of the intestinal type; cancers of the gastric cardia have

been increasing in incidence

- worldwide, gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer

- worldwide, there is considerable geographic variation in the incidence of gastric cancer: Japan has an

incidence ten times higher than in the U.S.

- Chile, Iceland, Costa Rica have incidences of the disease much higher than in the U.S.

- 2:1 male to female ratio; higher incidence among blacks than whites in the U.S.

- peak incidence is in the sixth and seventh decades of life

- Etiology

- Diet

- gastric cancer appears to be correlated with foods containing high levels of salt, nitrates, and nitrites

- nitrates and nitrites can be converted to carcinogens, the n-nitrosamines

- ascorbic acid can prevent the conversion of nitrites to nitrosamines

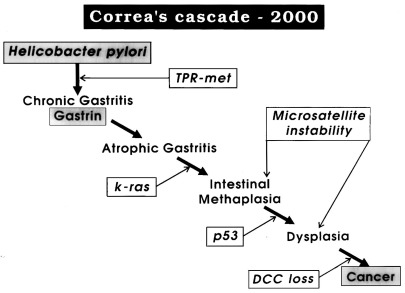

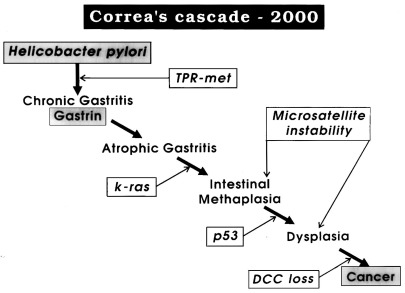

- Helicobacter Pylori

- parallels exist between regional rates of gastric cancer and H. pylori infection

- H. pylori is more associated with the intestinal type cancer than with the diffuse type

- chronic H. pylori infection leads to acute and chronic gastritis, which may progress to chronic

atrophic gastritis with metaplasia, followed by dysplasia

- in addition, chronic atrophic gastritis leads to achlorhydria with consequent anaerobic bacterial overgrowth

- anaerobic organisms are capable of reducing nitrate to nitrite, which induces the synthesis of nitroso compounds

that possess mutagenic potential

- H. pylori also causes production of growth regulatory peptides

- trials aimed at gastric cancer prevention by the treatment of H. pylori infection are currently under way

- Polyps

- adenomatous gastric polyps are rare but carry a high risk for the development of cancer

- the risk is greatest for polyps > 2 cm

- fundic gland polyps are associated with PPI use, and do not appear to have malignant potential

- Previous Gastric Surgery

- gastric surgery for benign conditions increases the risk of gastric cancer twofold to sixfold

- occurs 15 to 20 years following gastric resection and is most commonly associated with a

Billroth II reconstruction

- vagotomy and antrectomy causes hypochlorhydria, leading to bacterial overgrowth

- bacterial overgrowth can lead to increased conversion of nitrites to nitroso compounds,

which can cause metaplasia, dysplasia, and eventually cancer

- the continuous bathing of the gastric mucosa with alkaline secretions is likely another important factor

- Hereditary Risk Factors

- hereditary diffuse gastric cancer results from a gene mutation in E-cadherin, a cell adhesion molecule

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome results from a mutation in p53

- hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome) is associated with gastric and ovarian cancers

- Peutz-Jegher’s syndrome

- Other Risk Factors

- pernicious anemia results in achlorhydria

- PPIs, which result in achlorhydria and corpus gastritis, have not been shown to cause gastric cancer

- Pathology

- Gross Appearance

- gastric cancers are divided into 4 subtypes based on macroscopic appearance:

polypoid, fungating, ulcerative, and scirrhous (linitis plastic)

- scirrhous tumors infiltrate the entire wall of the stomach and cover a very large surface area

- distribution of tumors: 40% distal, 30% middle, 30% proximal

- Histologic Appearance

- 2 major histologic types: intestinal and diffuse

- additional histologic subtypes include papillary, tubular, mucinous, and signet-ring cell

- Intestinal Type

- localized to the antrum

- arises in the setting of intestinal metaplasia

- tumors have a glandular structure resembling colon cancer

- predominates in high risk areas

- more closely associated with H. pylori than the diffuse type

- Diffuse Type

- arises out of single-cell mutations within normal gastric glands

- not associated with intestinal metaplasia

- poorly differentiated

- associated with more proximal tumors

- seen more often in women and young patients

- stage for stage, has a worse prognosis than the intestinal type

- Methods of Spread

- regional lymphatics

- direct extension into adjacent organs (liver, spleen, pancreas, transverse colon and mesentery)

- systemically via the portal vein

- transperitoneally (ovaries – Krukenberg’s tumor, pelvic cul-de-sac – Blumer’s shelf)

- Early Gastric Cancer (EGC)

- histologically confined to the mucosa and submucosa

- may have lymph node involvement (3%, mucosal tumors; 20% submucosal tumors)

- comprises > 50% of all gastric cancers diagnosed in Japan, largely as a result of mass screening programs

- comprises < 10% of gastric cancers diagnosed in the U.S.

- cure rates are greater than 90% at 5 years

- Pathologic Staging

- Classification by Location

- tumors involving the G-E junction with the tumor epicenter no more than 2 cm into the proximal

stomach are now classified as esophageal cancers

- G-E junction tumors with their epicenter located more than 2 cm into the proximal stomach are

classified as stomach cancers

- TNM Classification

- T Category

- T1a: tumor does not invade the submucosa

- T1b: tumor invades the submucosa

- T2: tumor invades the muscularis propria

- T3: penetrates the subserosal connective tissue but not the serosa

- T4: penetrates the serosa or invades adjacent organs

- N Category

- number of examined nodes affects the accuracy of staging and influences survival

- AJCC guidelines recommend that a minimum of 16 nodes be removed for pathologic evaluation,

and that 30 or more is preferable

- Clinical Manifestations

- Early Gastric Cancer (T1)

- symptoms of early gastric cancer are vague and nonspecific

- may mimic symptoms of gastric ulcer disease

- In the U.S, they are usually found incidentally on EGD for GERD or peptic ulcer disease

- Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer

- weight loss, abdominal pain, and anorexia are the most common symptoms

- nausea and vomiting may occur if distal lesions obstruct the pylorus

- dysphagia is a dominant symptom for cancer of the cardia

- hematemesis is unusual, but anemia and occult blood in the stool are common

- 10% of patients present with evidence of widespread disease, including hepatomegaly,

ascites, supraclavicular adenopathy (Virchow’s node), ovarian metastases (Krukenberg’s tumor),

Blumer’s shelf, umbilical nodule (Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule)

- Diagnosis and Clinical Staging

- upper endoscopy with biopsy is the most accurate diagnostic tool

- double-contrast barium UGI is a complementary study but it is difficult to

distinguish benign from malignant ulcers by this study

- abdominal/pelvic CT scanning should be done for preoperative staging

- endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provides accurate data about the depth of tumor

penetration through the stomach wall and showing enlarged perigastric nodes

- EUS is most valuable in distinguishing early gastric cancers from more advanced tumors

- PET-CT is useful for evaluating for distant metastases

- laparoscopy may be used as a staging tool to determine the presence of small liver or intraperitoneal

metastases not seen on CT scan

- Treatment

- Palliation

- unfortunately, many patients with gastric cancer present with advanced disease

(distant metastases or invasion of a major vessel)

- patients with advanced disease who are not bleeding or obstructed should not be explored

- if the patient is bleeding or obstructed, then a palliative resection can be offered to improve

the patient’s quality of life

- it is controversial whether a total gastrectomy is an appropriate palliative intervention

- if, at exploration, an obstructing lesion is not resectable, then a gastrojejunostomy can be performed

- for patients with metastatic obstructing proximal gastric tumors, palliation is best achieved with stents

or endoscopic laser therapy

- radiation and chemotherapy offer little in the way of palliation

- Curative Resection

- surgery is the only potentially curable therapy (R0 resection)

- much controversy exists regarding the extent of gastric resection and the completeness of the lymphadenectomy

- location of the primary tumor is defined as distal third, middle third, upper third, and cardia

- an adequate proximal and distal margin should be 4 to 6 cm from the tumor and should be confirmed

with intraoperative frozen section

- Tumors of the Distal Third

- best managed with subtotal gastrectomy (75%), to include 2 to 3 cm of duodenum

- left and right gastric vessels, left and right gastroepiploic vessels are ligated at their origin

- greater and lesser omentum are also removed

- resection includes the suprapyloric and infrapyloric nodes, as well as the nodes along the greater

and lesser curves

- 16 or more nodes should be removed

- splenectomy is usually not part of the procedure

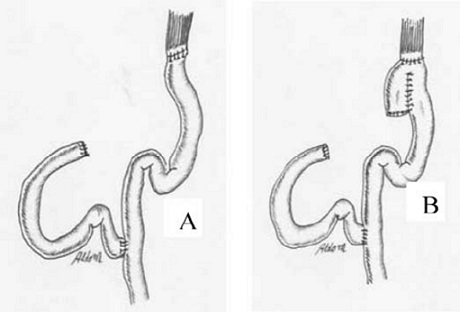

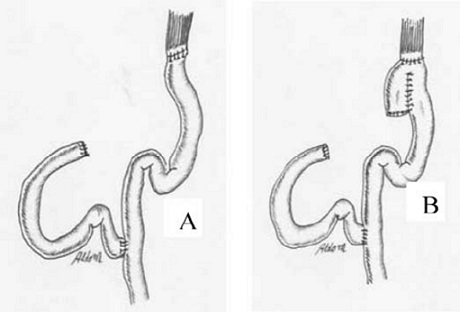

- reconstruction is by Roux-en-Y or Billroth II gastrojejunostomy

- Billroth I reconstruction is contraindicated because of the risk of local recurrence and

resulting obstruction

- Tumors of the Middle Third

- usually require a total gastrectomy

- if the tumor is small and well-differentiated, it may be possible to preserve a small cuff of

the upper stomach

- splenectomy and/or distal pancreatectomy for greater curve tumors may be required

- reconstruction is by a Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy, with or without the creation of a pouch

- Tumors of the Upper Third

- most surgeons prefer total gastrectomy

- another option is a proximal subtotal gastrectomy, but this operation may leave behind nodes

along the lesser curve

- need a generous esophageal margin with frozen section control

- another option is an esophagogastrectomy through a combined laparotomy-thoracotomy approach

- Tumors of the Cardia and Gastroesophageal Junction

- management is controversial

- surgical options include total gastrectomy and esophagogastrectomy with anastomosis in the chest or neck

- an anastomosis in the chest is prone to reflux and life-threatening leaks

- an anastomosis in the neck can be performed using 3 different incisions: (1) right thoracotomy,

(2) midline laparotomy, (3) left cervical

- alternatively, the thoracic dissection can be performed using the transhiatal approach,

obviating a thoracotomy

- intestinal continuity is reestablished with a left (preferable) or right colon interposition

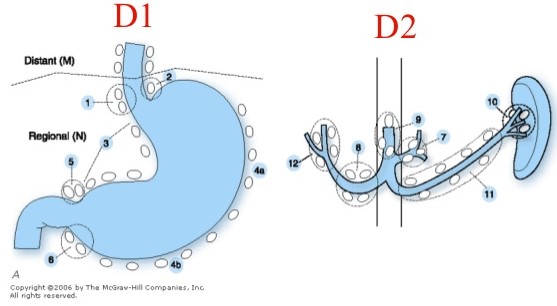

- Extent of Lymphadenectomy

- remains an area of great controversy

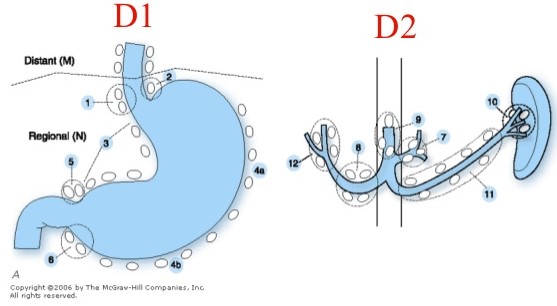

- D1: perigastric nodes; has been the standard procedure in the US

- D2: D1 + removal of nodes along the left gastric, hepatic, celiac, and splenic arteries, as well as

splenic hilar nodes

- D3: D1 + D2 + removal of periaortic and porta hepatis nodes

- multiple randomized trials have not shown a survival benefit with D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy,

or with D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy

- more recent analysis suggests that a D2 lymphadenectomy may be beneficial if it can be done

without the increased morbidity/mortality of a splenectomy and distal pancreatectomy

- Chemotherapy and Radiation

- Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

- several recent studies from Europe have shown improved 5-year survival rates over surgery first for

stage II and III disease

- one advantage of preoperative chemotherapy is that adequate postoperative chemotherapy is often limited

by postoperative complications and slow recovery

- Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Radiation

- postoperative chemotherapy alone is indicated for patients who have had a D2 lymphadenectomy

- for patients who have had less than a D2 lymphadenectomy, postoperative chemoradiation is indicated

Gastric Lymphoma

- Presentation

- primary gastric lymphoma presents in a similar fashion to that of adenocarcinoma

- anorexia and weight loss are the most common symptoms

- early satiety is common as the gastric wall becomes thickened and non-distensible

- patients may present with complications: bleeding, perforation, obstruction

- systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats) may be present but are rare

- diagnosis is made by endoscopy and biopsy

- Pathology

- most common gastric lymphoma is diffuse large cell B cell lymphoma (55%), followed by MALT lymphoma (40%)

- H.pylori and immunodeficiencies are risk factors for gastric lymphoma

- Evaluation

- bone marrow biopsy, CT chest and abdomen to detect distant disease

- enlarged nodes should be biopsied

- Treatment

- Chemotherapy

- most patients are treated with chemotherapy alone

- risk of perforation with chemotherapy is ~ 5%

- Surgery

- reserved for complications: bleeding, perforation, gastric outlet obstruction,

symptomatic recurrences after treatment failure

- as effective as chemotherapy for limited gastric disease

- H. pylori Eradication

- successful eradication of H.pylori results in remission in 75% of cases of MALT lymphoma

- careful follow up is necessary to document regression

References

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 1213 – 1231

- Cameron, 11th ed., pgs 87 – 96

- UpToDate. Surgical Management of Gastric Cancer. Mansfield MD, Paul. Aug 02, 2019. Pgs 1 – 49