Primary Survey (ABCDE)

- Airway with Cervical Spine Protection (A)

- inadequate delivery of oxygenated blood to the brain and other vital structures is the quickest

killer of the injured patient

- prevention of hypoxia requires a protected, unobstructed airway and adequate ventilation

- airway and ventilation take priority over all other conditions

- Clinical Assessment

- if the patient is able to communicate verbally, the airway is not likely to be in immediate

jeopardy

- frequent reassessment of airway patency and adequacy of ventilation are critical

- rapid assessment of airway obstruction should include inspection for foreign bodies (teeth

and blood) and facial, mandibular, and laryngeal fractures

- tachypnea may be an early sign of airway obstruction

- patients who refuse to lie down may be having difficulty maintaining their airway

- look to see if the patient is agitated or obtunded:

- agitation suggests hypoxia

- obtundation suggests hypercarbia

- cyanosis of the nail beds or circumoral skin implies hypoxemia

- retractions and the use of accessory muscles suggests airway compromise

- listen for abnormal sounds:

- noisy breathing is obstructed breathing

- snoring, gurgling, and stridor may be associated with partial occlusion of the

larynx

- hoarseness implies obstruction of the larynx

- an abusive or belligerent patient may be hypoxic

- feel for the location of the trachea and determine if it is midline

- chin lift or jaw thrust are the initial maneuvers to establish a patent airway

- C-spine must be protected while assessing and managing the airway – manually stabilize the

patient’s head and neck using inline mobilization techniques

- C-Spine Protection

- spinal cord must be protected until spinal injury has been ruled out by clinical assessment

and/or imaging

- removal of helmets and collars is a two-person job (one person provides manual in-line

immobilization while the other removes the helmet or collar)

- in-line immobilization is mandatory during all procedures to maintain or obtain an airway

- Supplemental Oxygen

- should be administered immediately to all trauma patients

- Airway Maintenance Techniques

- tongue may fall backwards and obstruct the hypopharynx if the patient has a decreased level

of consciousness

- this form of obstruction can be corrected by the chin lift or jaw thrust maneuvers and

maintained with an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway

- Oropharyngeal Airway

- cannot be used in a conscious patient because it will induce gagging, vomiting,

and aspiration

- when inserting, must be careful not to push the tongue backward and block the airway

- Nasopharyngeal Airway

- better tolerated in a responsive patient

- Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

- not a definitive airway

- useful if intubation has failed, or is unlikely to succeed

- requires appropriate training

- if an LMA is in place, must make plans for a definitive airway

- intubating LMA (ILMA) is a device that allows for intubation through the LMA

- Additional Airway devices

- laryngeal tube airway

- multilumen esophageal airway

- Definitive Airway

- Definition

- requires a tube present in the trachea with the cuff inflated, the tube connected to

some form of oxygen-enriched assisted ventilation, and the airway secured in place

with tape

- 3 varieties: orotracheal tube, nasotracheal tube, cricothyroidotomy

- Indications

- apnea

- inability to maintain a patent airway by other means

- airway protection from blood and vomitus

- impending airway compromise:

- large or expanding neck hematoma

- laryngeal/tracheal injury

- maxillofacial trauma (especially bilateral mandible fractures)

- facial burns

- inhalation injury

- closed head injury with GCS < 8

- inadequate oxygenation

- inadequate ventilation

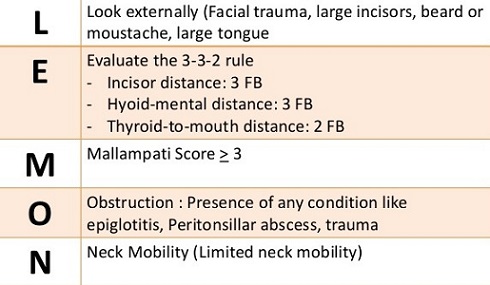

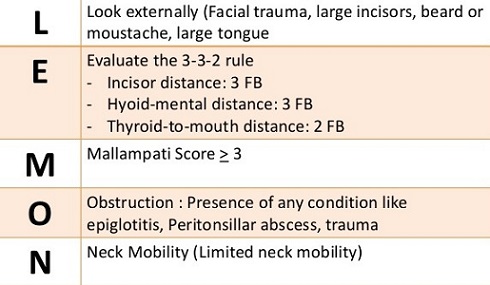

- LEMON Airway Assessment

- used to predict the difficulty of intubation

- Techniques

- Orotracheal Intubation

- most commonly chosen technique

- can be performed rapidly under direct vision

- suitable in both awake and apneic patients

- 2-person technique with in-line cervical spine immobilization should be used

- drug-assisted technique may be used in responsive patients

(succinylcholine/Etomidate), cricoid pressure

- if the cords can’t be visualized on laryngoscopy, a gum elastic bougie often

facilitates a successful intubation

- after intubation the chest and abdomen should be auscultated for equal

bilateral breath sounds

- CO2 monitor confirms proper intubation of the airway

- CXR is necessary to confirm proper positioning of the tube in the airway

- Nasotracheal Intubation

- blind technique requiring a spontaneously breathing patient

- contraindicated in apneic patients and patients with severe maxillofacial

trauma and basilar skull fractures

- most appropriate in hemodynamically stable patients with C-spine injuries

since less neck manipulation is required

- Cricothyroidotomy

- indicated when orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation is unsuccessful or

contraindicated

- must be performed with the neck in the neutral position

- easier, quicker, and associated with less bleeding than emergency

tracheostomy

- percutaneous tracheostomy should not be done because the patient’s neck must

be hyperextended

- should be converted to a formal tracheostomy as soon as the patient is

stable

- not recommended for children < 12 years’ old

- Jet Insufflation (Needle Cricothyroidotomy)

- provides oxygen on a short-term basis until a definitive airway can be placed

- 12- or 14-guage IV catheter is placed through the cricothyroid membrane into

the trachea

- catheter is then connected to high-flow (15 L/min) wall oxygen

- to provide ventilation, a hole is cut in the oxygen tubing and the hole is

covered for 1 second and uncovered for 4 seconds

- some exhalation occurs in the 4 seconds that oxygen isn’t flowing

- adequate oxygenation can only be maintained for 30 to 45 minutes

- CO2 slowly accumulates, further limiting the usefulness of this

method

- Breathing and Ventilation (B)

- Clinical Assessment

- airway patency does not assure adequate ventilation

- ventilation requires adequate functioning of the CNS, lungs, chest wall, and diaphragm, as

well as a patent airway

- look for symmetric and adequate chest wall excursion

- asymmetry suggests splinting or a flail chest

- labored breathing implies an imminent threat to the patient’s oxygenation

- listen for movement of air on both sides of the chest

- decreased or absent breath sounds over one or both hemithoraces indicates a thoracic

injury

- patients should be monitored with a pulse oximeter (monitors oxygenation, not ventilation)

- life-threatening thoracic injuries such as tension pneumothorax, open pneumothorax, and

massive hemothorax should be treated immediately

- Life Threating Emergencies

- Tension Pneumothorax

- Pathophysiology

- ‘one-way valve’ air leak occurs either from the lung or through the chest

wall

- air is forced into the thoracic cavity without any means of escape

- ipsilateral lung collapses and as the thoracic pressure increases, the

mediastinum is shifted to the opposite side, decreasing venous return

- Diagnosis

- clinical diagnosis: hypotension, respiratory distress, tracheal deviation,

neck vein distention, unilateral absence of breath sounds

- may be difficult to distinguish from cardiac tamponade

- Management

- immediate decompression with a large-bore needle into the 5th intercostal

space just anterior to the midaxillary line or finger thoracostomy

- converts the injury into a simple pneumothorax

- definitive treatment requires insertion of a chest tube

- Open Pneumothorax (‘Sucking Chest Wound’)

- Pathophysiology

- if a defect in the chest wall is greater than 2/3 the diameter of the

trachea, then air will follow the path of least resistance and pass

preferentially through the chest defect, rather than the mouth, with each

respiration

- result is impaired ventilation, leading to hypoxia and hypercarbia

- Management

- wound is covered with a sterile occlusive dressing and taped securely on

three sides

- goal is to create a flutter-type valve: as the patient breathes in,

the dressing is sucked over the wound, preventing air from escaping

- when the patient breathes out, the open end of the dressing allows air to

escape

- if the dressing is taped on all 4 sides, air can accumulate in the thoracic

cavity, resulting in a tension pneumothorax

- a chest tube should be placed remote from the wound as soon as possible

- definitive surgical closure of the defect is often required

- Flail Chest

- Pathophysiology

- segment of the chest wall does not have bony continuity with the rest of the

thoracic cage

- results when 2 or more ribs are fractured in 2 or more places

- the unstable segment moves paradoxically during respiration

- major insult in flail chest results from the underlying pulmonary contusion,

not the chest wall instability

- associated pain with restricted chest wall motion also contributes to

hypoxia

- Diagnosis

- physical exam will show paradoxical chest wall movement

- chest x-ray will show multiple rib fractures

- Management

- goal is to treat and/or prevent hypoxia

- many patients will require intubation and mechanical ventilation to

maintain an acceptable PO2

- aggressive pulmonary toilet and pain management (consider epidural catheter

or intercostal rib blocks) are the other cornerstones of management

- open reduction/internal fixation of the flail segment is rarely warranted

- Massive Hemothorax

- Mechanism of Injury

- results from the rapid accumulation of 1000 - 1500 cc of blood in the chest

cavity

- may result from blunt or penetrating trauma

- usually results from a systemic arterial (intercostal, internal mammary) or

pulmonary hilar injury

- since the lung is a low-pressure system, bleeding from the lung parenchyma

does not cause massive hemothorax

- Diagnosis

- hypovolemic shock associated with absence of breath sounds and/or dullness

to percussion on one side of the chest

- chest x-ray shows a large fluid collection

- Management

- insertion of a chest tube (28 – 32 F) that is connected to an autotransfusion

device

- restoration of blood volume with crystalloid and blood

- most patients with initial blood loss >1500 cc will require thoracotomy

- patients with ongoing blood loss of 250 cc/hr for 3 hours are also likely to

need thoracotomy

- patient’s physiologic status is the best guide for the need for surgery

- Cardiac Tamponade

- Pathophysiology

- most commonly results from penetrating injuries

- pericardial sac is a fixed fibrous structure that does not distend and as

little as 150 cc of blood may impair diastolic filling

- Diagnosis

- can be difficult in the trauma setting

- Beck’s triad (present in 1/3 of cases): 1) distended neck veins, 2) muffled

heart sounds, 3) hypotension

- Kussmaul’s sign: rise in venous pressure with inspiration when breathing

spontaneously

- tension pneumothorax can mimic tamponade

- pulseless electrical activity (PEA) in the absence of hypovolemia and

tension pneumothorax suggests cardiac tamponade

- FAST is a valuable non-invasive tool for showing fluid in the pericardial

sac (false-negative rate = 5%)

- Management

- volume resuscitation will transiently improve cardiac output

- subxiphoid pericardiocentesis is both diagnostic and therapeutic

- patients with a positive pericardiocentesis or FAST exam will require

thoracotomy or sternotomy for definitive repair of the heart

- Role of ER Thoracotomy

- patients with penetrating chest injuries who arrive pulseless, but with myocardial

electrical activity, may be candidates for immediate resuscitative thoracotomy

- patients sustaining blunt injuries who arrive pulseless are not candidates for ER

thoracotomy

- therapeutic maneuvers that can be accomplished with ER thoracotomy include:

- release of pericardial tamponade

- direct control of exsanguinating hemorrhage

- open cardiac massage

- cross-clamping of the descending aorta to slow blood loss below the

diaphragm and increase perfusion to the brain and heart

- Circulation with Hemorrhage Control (C)

- hemorrhage is the main cause of early death following injury

- hypotension following injury is hypovolemic in origin until proven otherwise

- bleeding will be from one or more of 5 locations: chest, abdomen, retroperitoneum

(often pelvic fractures), long bones, and external sites

- Clinical Assessment

- tachycardia is the earliest physiologic response to blood loss

- cutaneous vasoconstriction is another early sign of blood loss

- systolic blood pressure may not fall until 30% of the blood volume has been lost

- altered level of consciousness as a result of decreased cerebral perfusion accompanies

profound blood loss

- acute blood loss cannot reliably be estimated using the hemoglobin or hematocrit

concentration

- CXR to evaluate for thoracic bleeding

- pelvic x-ray to identify pelvic fractures

- FAST, DPL to evaluate for intra-abdominal bleeding

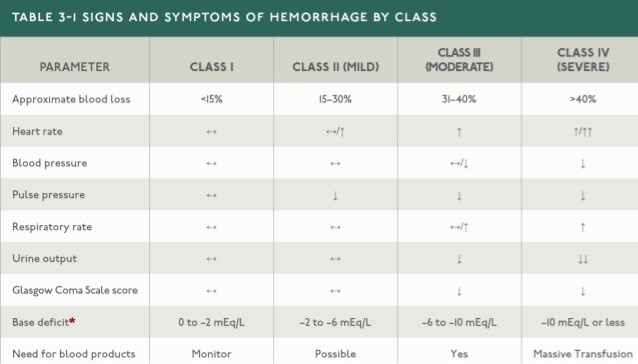

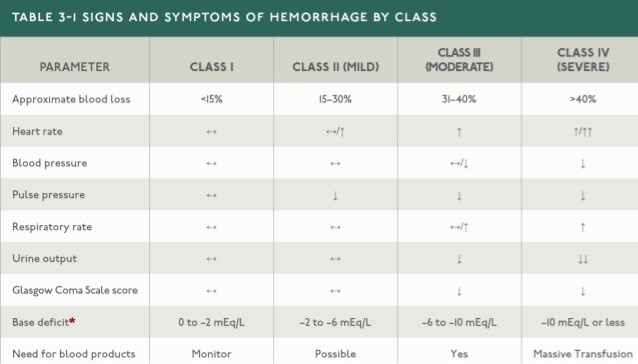

- ATLS Classification of Hemorrhagic Shock

- athletes (conditioning), elderly patients (medications), and pregnant patients

(hypervolemia) may deviate from this classification

- Control of Blood Loss

- external blood loss is managed by direct manual pressure on the wound

- pelvic binder or pneumatic antishock garment may be used to control bleeding from pelvic

fractures

- long bone fractures should be splinted

- chest tube for intrathoracic bleeding

- Resuscitation

- Vascular Access

- 2 large-bore peripheral IVs should be started immediately

- if peripheral access cannot be obtained, central lines, cutdowns, or intraosseous

infusion can be used

- Initial Resuscitation

- blood should be sent immediately for type and crossmatch

- adults should receive an initial fluid bolus of one liter

- if the patient remains hypotensive, O-negative, type-specific, or type and

crossmatched blood should be given, depending upon their availability

- consider autotransfusion in any patient with a major hemothorax

- all IV fluids and blood products should be warmed to prevent hypothermia

- Massive Transfusion

- a small subset of patients will require massive transfusion (> 10 units PRBCs in

24 hours)

- goal is to minimize excessive crystalloid infusion

- PRBCs, FFP, and platelets are given in a balanced ratio (often 1:1:1)

- simultaneously, the source of bleeding must be controlled as fast as possible

- Coagulopathy

- consumption of coagulation factors, dilution, hypothermia, and acidosis all

contribute to coagulopathy

- many patients are also taking antiplatelet or anticoagulation drugs

- baseline PT, PTT, and platelet count should be obtained early

- prothrombin complex concentrate can be used to reverse Coumadin

- tranexamic acid – an antifibrinolytic agent – administered within 3 hours of injury

improves survival

- Disability (D)

- the goal of management is to maintain cerebral perfusion and oxygenation, thereby preventing

secondary brain injury

- a rapid neurological exam is performed at the end of the primary survey

- patient’s level of consciousness as well as pupil size and reactivity should also be assessed

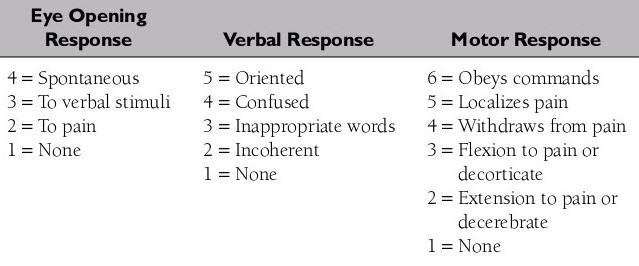

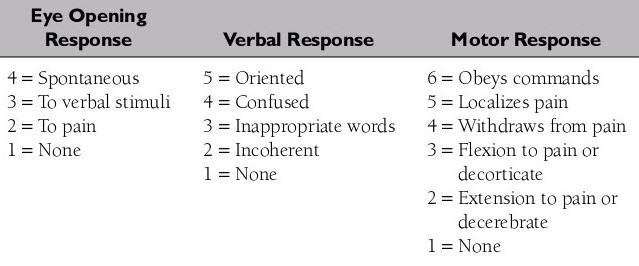

- Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a quick neurological evaluation that is predictive of patient outcome

(motor response)

- Exposure and Environmental Control (E)

- patient must be completely exposed to facilitate a thorough examination

- after the patient has been assessed, then he must be covered with warm blankets or an external

warming device to prevent hypothermia

- the trauma room should be warm

- all IV fluids and blood products should be warmed before infusion

- Adjuncts to the Primary Survey

- EKG Monitoring

- required of all trauma patients to detect dysrhythmias

- Pulse Oximeter

- measures the oxygen saturation and heart rate

- Blood Pressure Monitor

- automated device is used and frequently cycled

- Urinary Catheter

- urinary output is a sensitive indicator of volume status and reflects renal perfusion

- transurethral catheter placement is contraindicated if urethral transection is suspected:

- blood at the penile meatus

- perineal ecchymosis

- blood in the scrotum

- pelvic fracture

- if urethral injury is suspected, then a retrograde urethrogram must be performed before the

catheter is inserted

- Nasogastric Tube

- purpose is to decrease gastric distention and reduce the risk of aspiration

- if a fracture of the cribriform plate is suspected, then the tube should be inserted orally

to prevent intracranial passage

- insertion of the gastric catheter may induce gagging and vomiting and cause the specific

problem it was intended to prevent: aspiration

- X-rays and Diagnostic Studies

- X-rays

- Chest X-ray

- should be obtained in all patients with blunt or penetrating torso trauma or who are

in respiratory distress

- additional indications include any unconscious patient or any patient going to the

operating room

- Pelvic X-ray

- should be obtained in any patient sustaining blunt trauma to the torso

- additional indications include gross hematuria, gross blood on rectal or vaginal

examination, and unexplained hypotension

- Diagnostic Studies

- Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage (DPL)

- 98% sensitive for intraperitoneal bleeding

- used in hemodynamically unstable blunt trauma patients if FAST is not available

- only absolute contraindication is an existing indication for laparotomy

- relative contraindications include previous abdominal surgery, morbid obesity, and

coagulopathy

- Diagnostic Ultrasound (FAST)

- as accurate as DPL for detecting hemoperitoneum, and has largely replaced DPL in

most trauma centers

- requires special training

- may be repeated at intervals to detect progressive hemoperitoneum

Secondary Survey

- History

- allergies, medicines, past and current illnesses, previous surgery, and the events surrounding

the injury and mechanism of injury are the critical elements of the history

- family members and prehospital personnel often have to provide these details

- Physical Examination

- the patient must be completely examined: head and skull, maxillofacial, neck, chest, abdomen,

perineum/rectum/vagina, musculoskeletal, and a complete neurological examination

- ‘a finger in every orifice’

- Adjuncts to the Secondary Survey

- specialized tests may be performed to identify specific injuries: CT scans, angiograms, endoscopy,

ultrasound, extremity x-rays, additional c-spine views

- no specialized test should be performed until the patient has been fully examined and his

hemodynamic status has normalized

References

- ATLS Student Course Manual 2012, 9th ed., Pgs 2 – 60

- ATLS Student Course Manual 2018, 10th ed., pgs 2 - 61

- Cameron, 13th ed., pgs 1105 - 1111, 1124 - 1131