Anatomy and Physiology

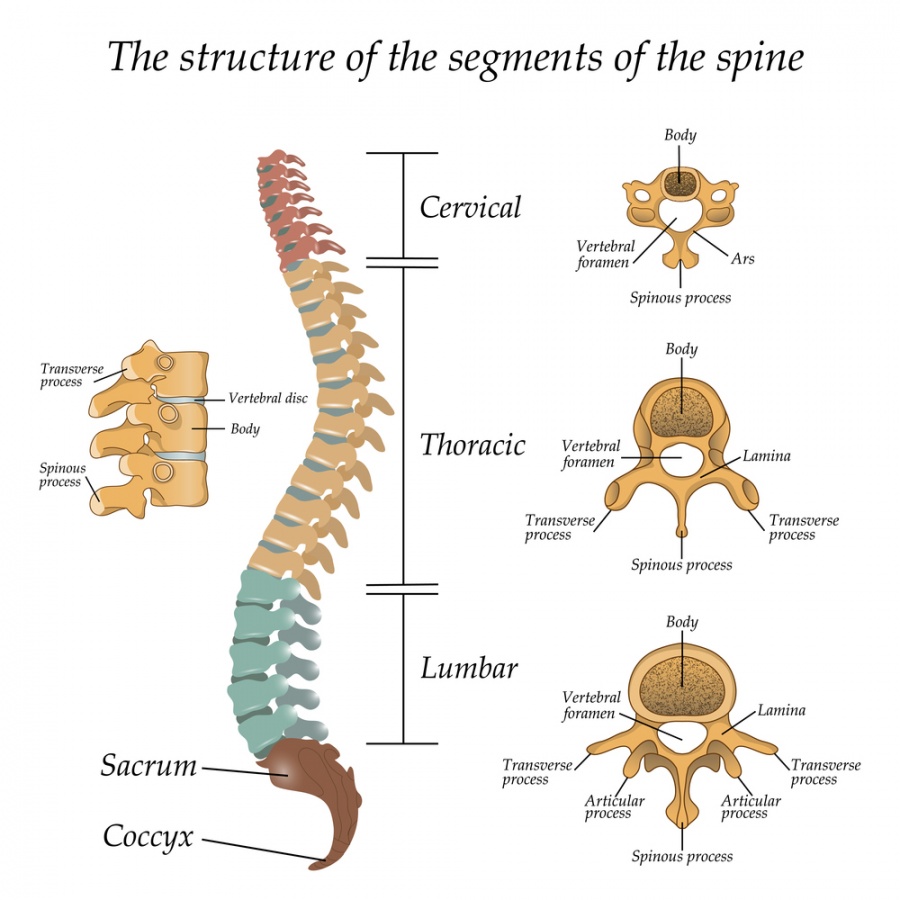

- Spinal Column

- consists of 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar vertebrae, sacrum, and coccyx

- vertebral body forms the main weight-bearing column

- Spinal Cord Anatomy

- originates from the medulla oblongata at the foramen magnum

- ends at ~ L1 as the conus medullaris

- below L1 is the cauda equina

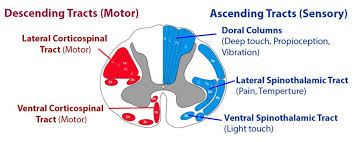

- Spinal Cord Tracts

- 3 paired tracts can be assessed clinically: 1) corticospinal tract, 2) spinothalamic tract, 3) dorsal columns

- Dermatomes

- area of skin innervated by a segmental nerve root

- knowledge of the major dermatome levels aids in determining the level of injury and in assessing neurologic improvement or deterioration

- Myotomes

- key muscles should be tested for strength on both sides

- graded on a 6-point scale (0-5) from paralysis to normal strength

- Spinal Cord Syndromes

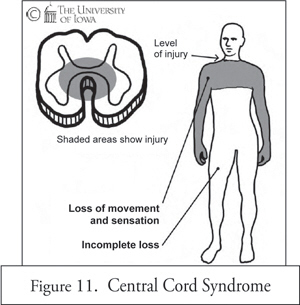

- Central Cord Syndrome

- characterized by greater loss of motor strength in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities

- results from compromise of the cord in the distribution of the anterior spinal artery

- since the motor fibers of the cervical segments are anatomically arranged toward the center of the cord, this is the region most affected

- typically occurs after a hyperextension injury – forward fall with a facial impact

- may occur with or without cervical spine fracture or dislocation

- prognosis for recovery is better than in other incomplete injuries

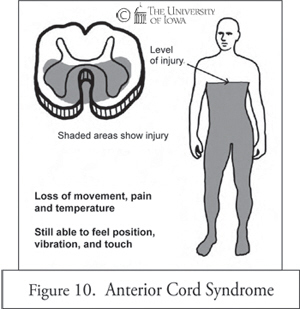

- Anterior Cord Syndrome

- characterized by loss of corticospinal and corticothalamic pathways with preservation of dorsal column function

- clinically, results in paraplegia and loss of pain and temperature sensation distal to the injury

- position sense, vibration, and deep pressure are preserved

- may result from occlusion or spasm of the anterior spinal artery

- prognosis for recovery is poor

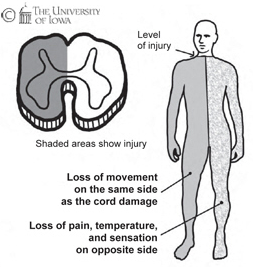

- Brown-Séquard Syndrome

- results from hemisection of the cord

- usually due to a penetrating injury

- consists of ipsilateral motor loss and loss of position sense and contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation

| Nerve Root | Level of Sensation |

|---|---|

| C5 | area over deltoid |

| C6 | thumb |

| C7 | middle finger |

| C8 | little finger |

| T4 | nipple |

| T8 | xiphoid |

| T10 | umbilicus |

| T12 | symphysis pubis |

| L3 | anterior thigh |

| L4 | medial thigh |

| L5 | space between 1st and 2nd toes |

| S1 | lateral border of foot |

| S4/S5 | perianal region |

| Nerve Root | Motor Function |

|---|---|

| C3/C4 | diaphragm |

| C5 | shoulder shrug (deltoid) |

| C6 | elbow extensors (triceps) |

| C7 | wrist flexors |

| C8 | finger flexors |

| T1 | finger abductors |

| L2 | hip flexors (iliopsoas) |

| L3/L4 | knee extensors (quads) |

| L5/S1 | ankle dorsiflexors |

| S1/S2 | ankle plantar flexors |

Spinal Cord Trauma

- Clinical Evaluation

- spinal column injury, with or without neurologic deficits, must always be sought and excluded in a patient with multiple trauma

- any injury above the clavicle should prompt a search for a C-spine injury

- 5% of head-injured patients have an associated spinal injury

- 10% of patients with c-spine fracture have a second noncontiguous vertebral column fracture

- as long as the c-spine is protected, evaluation of the spine should be deferred until other life-threatening problems are stabilized

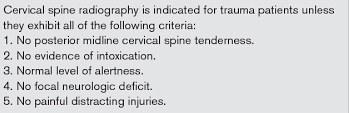

- in an awake, non-intoxicated patient who is neurologically intact and has no distracting pain, the absence of pain or tenderness along the spine virtually excludes the presence of a spinal injury

- Radiologic Evaluation

- required in any patient with a neurologic deficit, midline neck pain, tenderness on exam, or in any patient with an unreliable exam or distracting injury

- if available, axial CT from the occiput to T1 with sagittal and coronal reconstructions is the preferred imaging technique

- if CT is unavailable, then plain films consisting of lateral, AP, and open-mouth odontoid views should be obtained

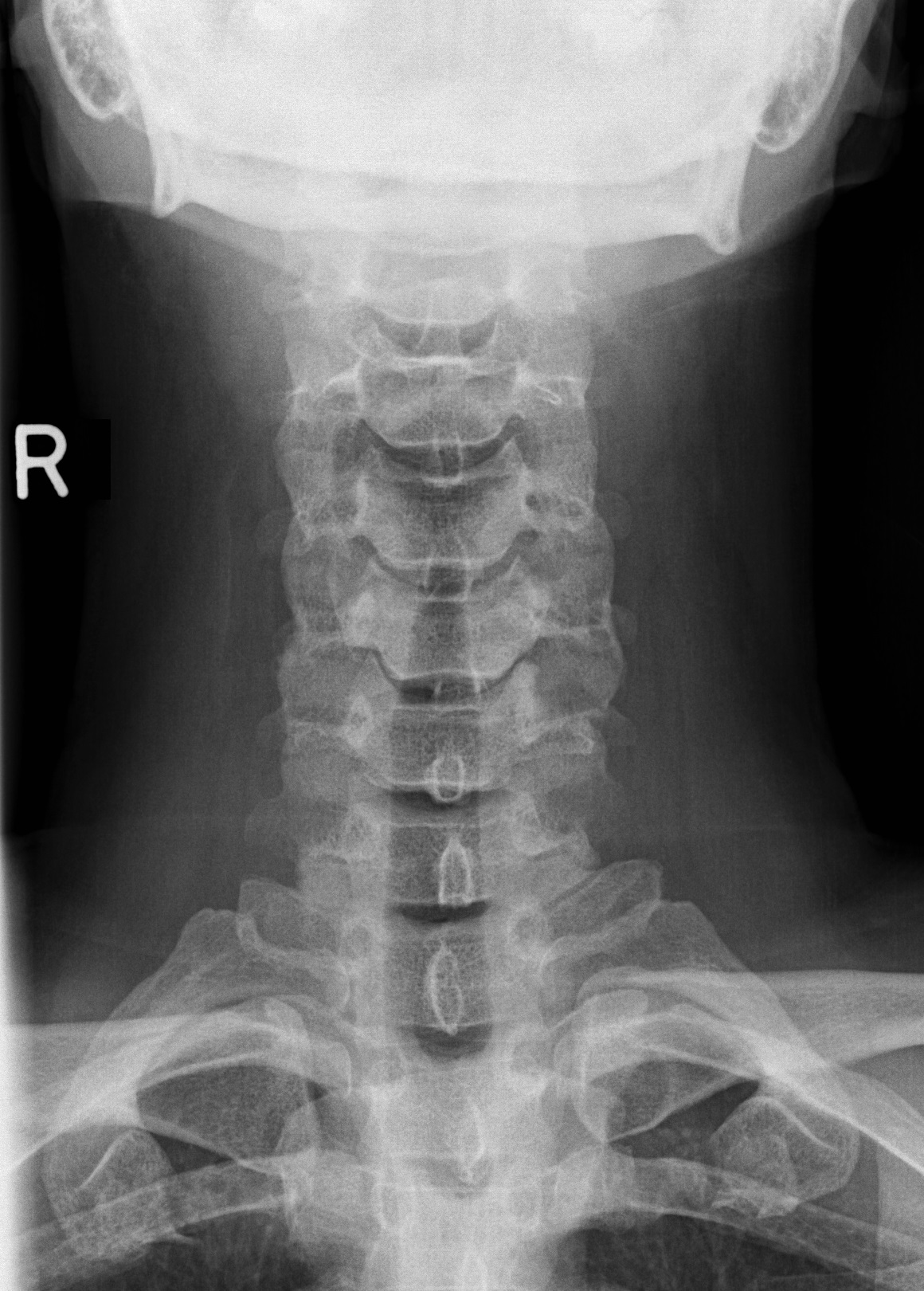

- C-Spine

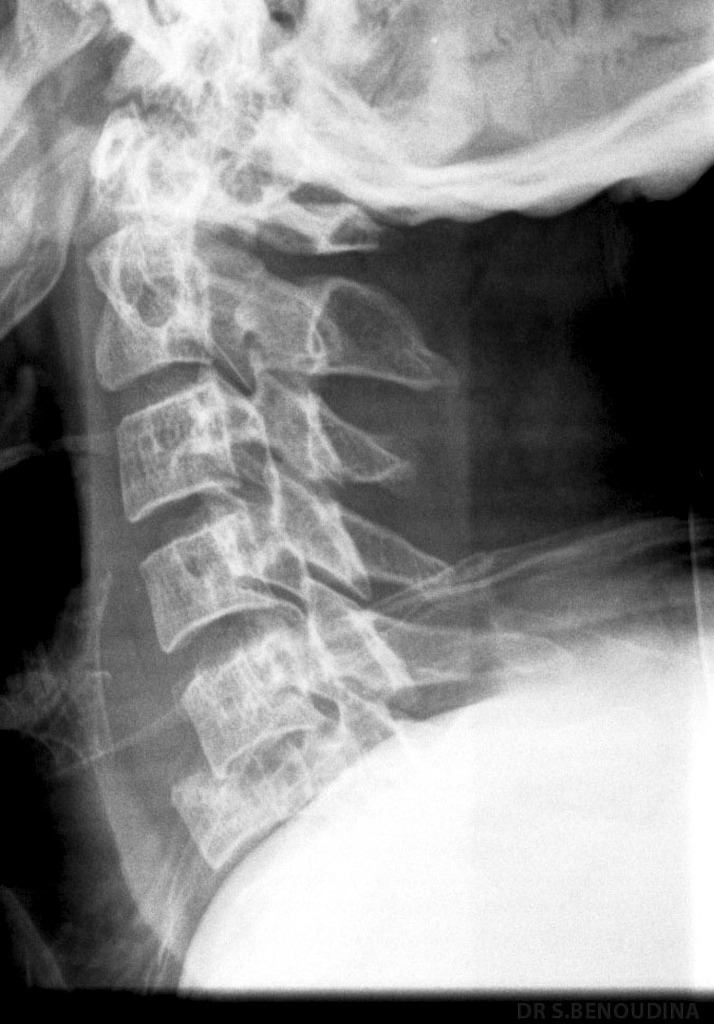

- lateral C-spine film should be obtained after life-threatening problems are controlled

- 85% of C-spine injuries will be identified on the lateral x-ray

- the addition of an open-mouth odontoid view and AP view (for detection of facet joint dislocations) increases the sensitivity for fracture identification to 97%

- CT scans should be used to evaluate suspicious areas or areas which cannot be adequately visualized with standard films

- 10% of patients with a C-spine fracture will have a second associated noncontiguous spinal column fracture and vice versa

- the entire spine should be radiographically screened in any patient with a C-spine fracture

- Normal Lateral C-Spine

- Normal AP View

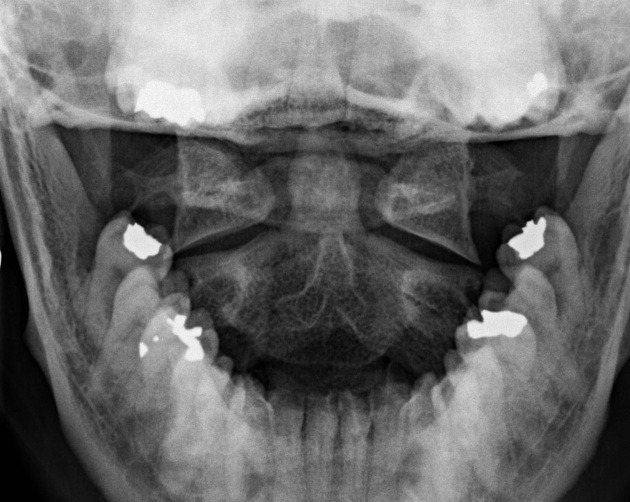

- Normal Open-Mouth (Odontoid) View

- C-Spine Injuries

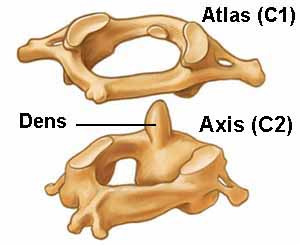

- C1 Fractures

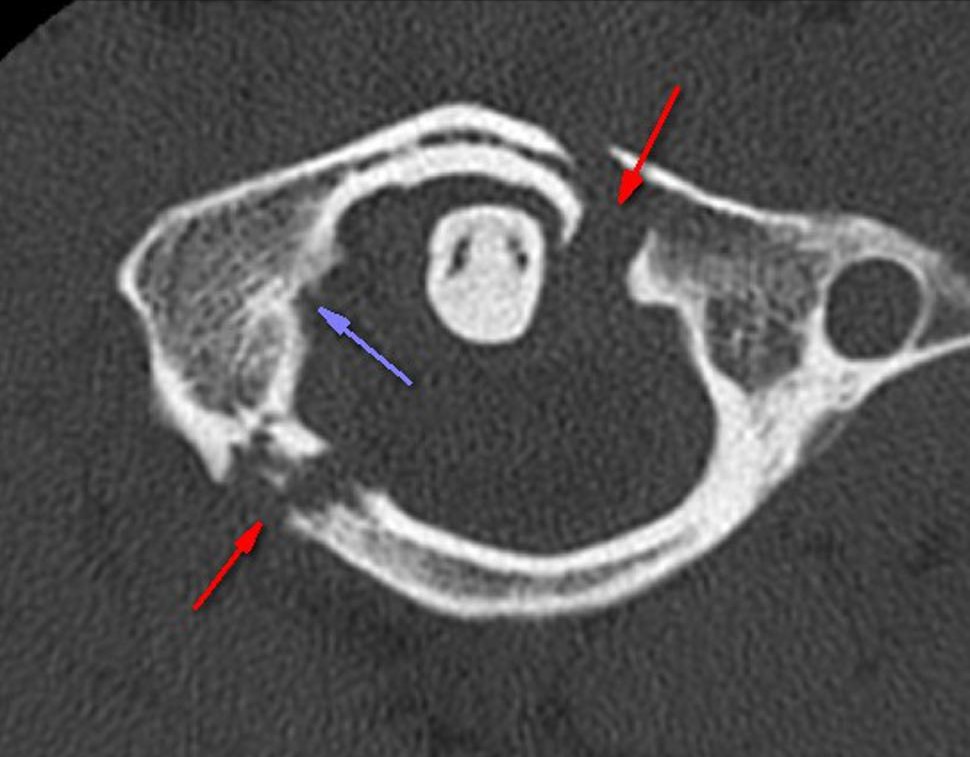

- most common C1 injury is the Jefferson burst fracture, which consists of disruption of both the anterior and posterior rings and lateral displacement of the lateral masses

- usual mechanism is axial loading with the head in a neutral position

- best seen on the open-mouth odontoid view and can be confirmed by CT scan

- often not associated with spinal cord injury but is an unstable injury

- initially treated with a cervical collar

- C2 Fractures

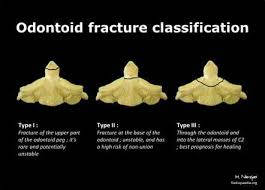

- Odontoid Fractures

- account for 60% of axis fractures

- 3 types: 1) type 1 fractures involve the tip of the odontoid, 2) type 2 fractures occur through the base of the dens and are the most common, 3) type3 fractures occur at the base of the dens and extend into the body of the axis

- relatively few associated spinal cord injuries

- Posterior Elements Fracture (Hangman’s Fracture)

- ~ 20% of axis fractures

- results from hyperextension of the neck

- Fractures and Dislocations of C3-C7

- most common level of fracture is C5

- most common level of subluxation is C5 on C6

- incidence of neurological injury increases dramatically with facet dislocations

- Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Fractures

- 4 main types: 1) anterior wedge compression, 2) burst injuries, 3) Chance fractures (transverse fractures through the vertebral body), 4) fracture-dislocations

- compression fractures are usually stable and often treated with a rigid brace

- burst fractures, Chance fractures, and fracture-dislocations are very unstable and require internal fixation

- Chance fractures are seen following MVAs where the driver was restrained only by a lap belt and are often associated with abdominal visceral injuries and retroperitoneal injuries

Management of Spinal Cord Injuries

- Immobilization

- c-spine injury requires spinal motion restriction by laying the patient on a firm surface with a rigid cervical collar

- patient’s neck should be in the neutral position

- ABCs take priority over the spinal injury

- during intubation, the neck must be maintained in a neutral position

- no effort should be made to reduce an obvious deformity

- all patients should be removed from the backboard as soon as possible to avoid decubitus ulcers

- if patient requires emergency surgery, the collar should be left on and the patient logrolled when moved to and from the OR table

- safe logrolling requires 4 or more people

- Documentation and Consultation

- patient’s initial physical exam must be well documented, so as to establish a baseline for any subsequent changes in neurological status

- obtain early consultation with a spine surgeon

- transfer patients with vertebral fractures or spinal cord injuries to a definitive care facility

- Treatment of Neurogenic Shock

- caused by a reduction in sympathetic discharge, resulting in decreased systemic vascular resistance

- there is also loss of venous tone, resulting in pooling of blood on the venous side of the circulation and decreased return of blood to the heart (reduction in preload and cardiac output)

- disruption of sympathetic input to the heart and adrenal medulla prevents reflex tachycardia secondary to hypovolemia

- patients should have their intravascular volume optimized, but must be careful to avoid fluid overload and pulmonary edema

- α-adrenergic agents (norepinephrine or phenylephrine) may be required to restore an adequate blood pressure

- atropine may be necessary to treat bradycardia

- Blunt Carotid and Vertebral Artery Injuries

- blunt trauma to the head and neck is a risk factor for carotid and vertebral artery dissection, thrombosis, or pseudoaneurysm

- untreated, these injuries have a 20% stroke rate

- indications for screening (Denver Criteria) with CT angiography include: C1-C3 fracture, c-spine fracture with subluxation, fractures involving the foramen transversarium, Lefort II or III fractures, near hanging with hypoxic brain injury, diffuse axonal injury with GCS < 6

- since the site of injury is usually surgically inaccessible, current treatment is with anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy if there are no contraindications

- there is an evolving role for carotid artery stenting