Carotid Artery Occlusive Disease

- Clinical Manifestations

- Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIA)

- defined as transient neurologic symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hrs

- most TIAs are brief, lasting 2 to 15 minutes, and rapid in onset

- most classic TIA is the transient loss of vision (amaurosis fugax) in the ipsilateral eye,

which results from an embolus to the ophthalmic artery, which is the first branch of the

internal carotid artery (ICA)

- other presentations include motor or sensory loss in the contralateral face, arm, or leg

- receptive or expressive aphasia may also result

- crescendo TIAs: more than 2 or 3 TIAs per day

- Reversible Ischemic Neurologic Deficit

- symptoms last longer than 24 hrs but resolve within 48 to 72 hours

- Completed Stroke

- a deficit that persists for > 72 hours

- Pathogenesis of TIA and Stroke

- extracranial carotid disease is responsible for 20% to 40% of strokes

- atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries is limited to the carotid bifurcation and proximal ICA

- Embolization

- embolization from a carotid artery atherosclerotic plaque is by far the most common cause of

cerebral ischemic events

- atherosclerotic plaques often contain ulcers: areas of the vessel that lack an intimal layer

- emboli may result from fragments of the cholesterol plaque that break off or from platelet

thrombi that become detached

- type, severity, and permanency of the cerebral event is determined by the size and eventual

location of the embolus

- Hypoperfusion

- flow-related ischemic events are rare

- because of extensive collateral pathways through the circle of Willis, cerebral perfusion is

rarely reduced to a critical level despite the presence of a severe carotid artery stenosis

- Thrombosis

- results from progressive enlargement of the atherosclerotic plaque

- if the thrombus does not propagate past the ophthalmic artery, then the total occlusion may

be clinically silent if collateral flow is sufficient

- if the thrombus propagates into the middle cerebral artery, then an ischemic event occurs

- Diagnosis

- Cervical Bruits

- represents turbulent blood flow

- may be detected in an asymptomatic patient on routine physical exam

- neither sensitive nor specific for carotid disease

- unless other atherosclerosis risk factors are present, a bruit is not an indication for screening

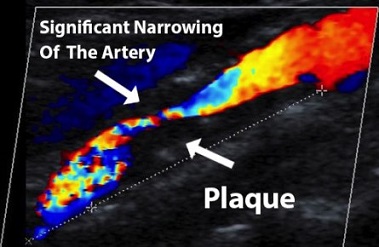

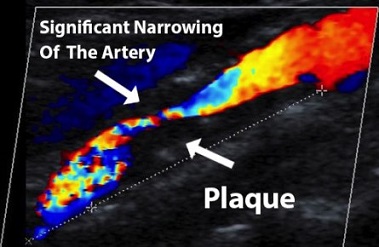

- Duplex Ultrasonography (DUS)

- provides anatomic information (B-mode) as well as flow velocity information

- severity of carotid stenosis is indirectly determined by measuring blood flow velocity: flow

increases as the lumen narrows

- DUS can also provide information regarding worrisome plaque morphology, including calcification,

ulceration, and intraplaque hemorrhage

- valuable in following patients with mild or moderate stenoses or as a screening tool in

at-risk patients

- CTA

- provides information about the aortic arch, common carotid artery, and intracerebral vasculature

- also is necessary to rule out intracerebral causes of the neurologic symptoms – tumor, AVMs,

intracranial bleeds

- MRA

- MRA is useful in defining lesion anatomy but requires the use of gadolinium, which is associated with

nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with CKD

- has largely been replaced by CTA

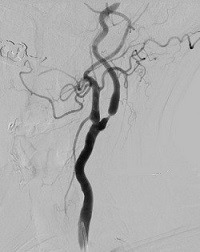

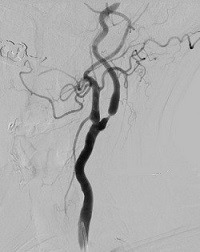

- Catheter Angiography

- best method for determining degree of stenosis

- however, it is associated with a 1% to 2% risk of stroke

- now only used if noninvasive tests are in disagreement with the clinical presentation

- Medical Management

- all patients with carotid atherosclerosis should have optimum medical therapy

- this includes antiplatelet therapy, statin therapy, and smoking cessation

- patients should also be treated for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes if present

- Carotid Revascularization

- even with best medical management, the risk of future ischemic events is high, especially in patients with

symptomatic disease

- the decision to pursue revascularization must weigh the baseline risk of stroke against the potential benefits

(lowered risk of a future stroke) and potential complications (stroke, MI, nerve injury)

- patients with complete carotid occlusion cannot benefit from revascularization

- patients who have undergone a persistent disabling stroke also do not benefit from revascularization

- men appear to benefit more from carotid revascularization than women

- carotid endarterectomy is preferred over carotid stenting, unless there are specific contraindications to

endarterectomy

- surgical skill matters: to operate on symptomatic patients, the surgeon and institution should have a

perioperative stroke and death rate < 6%

- Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA)

- Indications

- Symptomatic Patients

- recommendations are based on the NASCET trial published in 1991

- symptomatic patients with minimal stenoses (<50%) have equivalent results with medical

(aspirin) or surgical therapy

- patients with carotid artery stenosis ≥ 50% benefit from CEA followed by best medical therapy

- for patients with moderate stenoses (50% - 69%), the 5-year ipsilateral stroke rate was 22.2% in

the medical group, and 15.7% in the CEA group

- for patients with severe stenoses ≥ 70%, the 2-year ipsilateral stroke rate was 26% in the medical group,

and 9% in the CEA group

- importantly, with the development of Plavix and statins, the best medical management has changed since

the NASCET trial

- no trial has been conducted comparing best modern management to CEA

- Asymptomatic Patients

- indications for CEA are less clear-cut in asymptomatic patients

- risk of stroke and death with medical therapy is much less in asymptomatic patients than in symptomatic patients

- Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) showed that CEA benefits asymptomatic patients

with 60% - 99% stenoses if they have a life expectancy > 3 – 5 years

- the surgeon’s perioperative stroke and death rate must be < 3% to operate on asymptomatic patients

- Timing of Operation

- CEA should be performed between 2 days and 2 weeks for patients with a nondisabling stroke or TIA

- operation within 2 days is reserved for patients with crescendo TIAs or progressing stroke

- Operative Management

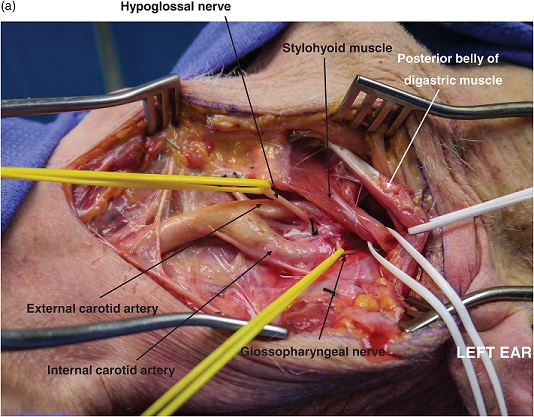

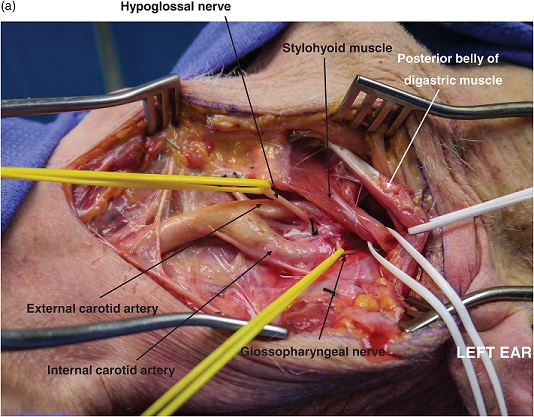

- Exposure

- oblique incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle provides the best exposure

- internal jugular vein is mobilized laterally after the facial vein is ligated and divided

- reflex bradycardia and hypotension may occur with dissection near the carotid bifurcation and

carotid body – this can be prevented with injection of 1% lidocaine into the carotid body

- must expose an adequate length of the common and internal carotid arteries to allow clamp placement

- hypoglossal nerve can be mobilized cranially to provide additional exposure of the internal carotid

- rarely, the digastric muscle must be divided, or the mandible displaced anteriorly, to expose a

high carotid bifurcation

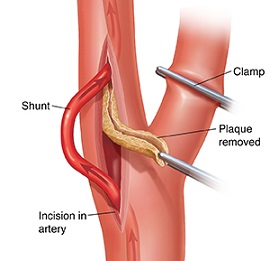

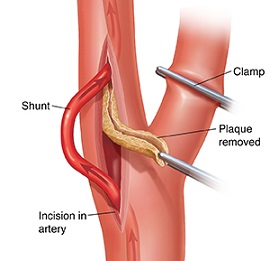

- Endarterectomy

- patient is heparinized, and the carotid vessels are clamped

- the ICA is clamped first to avoid embolization

- an arteriotomy is made in the common carotid artery and is carried onto the internal carotid

- the atherosclerotic plaque is carefully dissected off the arterial wall, starting on the CCA

- the proper plane is between the inner and outer medial layers – the remaining arterial wall

consists of adventitia and media

- dissection proceeds proximally and distally until normal intima is reached

- must avoid a distal intimal flap: if the distal intima is loose it must be tacked down with

sutures to avoid dissection

- Patch Closure of the Arteriotomy

- less risk of restenosis, especially in women, patients with small ICAs, and patients who continue

to smoke

- Shunting and Monitoring

- controversy exists regarding selective versus routine shunting

- some patients have insufficient collateral circulation to tolerate the period of carotid artery cross-clamping

- Routine Shunting

- used by many vascular surgeons

- not without disadvantages: shunts can damage the intima and impede the visualization of

the endpoint of the endarterectomy

- Selective Shunting and Monitoring

- monitoring techniques include monitoring neurologic status in an awake patient, EEG

monitoring, and measuring carotid artery stump pressure

- any change in neurologic status, slowing of the EEG waveform, or stump pressures < 50 mm Hg

mandate the placement of a shunt

- most patients with prior infarcts or contralateral carotid occlusion will require a shunt

- Postoperative Complications

- Stroke or TIA

- immediate ipsilateral neurologic deficits are considered to be the result of thrombosis

- emergent carotid duplex should be obtained, and if positive, mandates a return to the OR

- Cardiac Complications

- myocardial infarction is the leading cause of death after CEA

- patients with multiple cardiac risk factors require a cardiac clearance before surgery

- Nerve Damage

- nerves at risk include the hypoglossal nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, vagus nerve, marginal

mandibular nerve, superior laryngeal nerve, and spinal accessory nerve

- most frequent complication after CEA (4% to 9%)

- most are traction injuries and usually resolve within several weeks

- Hyperperfusion Syndrome

- after restoration of normal blood flow, the increased pressure in the cerebral vasculature causes

cerebral edema and hemorrhage

- occurs within 2 weeks of CEA

- symptoms/signs include headache, focal seizures, intracerebral hemorrhage

- prevention consists of strict blood pressure control in the immediate postop period

- treatment consists of ICU management of hypertension and seizures

- Concurrent Coronary Artery Disease

- patients who require CABG should undergo carotid artery screening

- patients who have symptomatic carotid disease may undergo CEA prior to CABG or concurrently

- the timing of CEA and CABG in patients with an asymptomatic carotid stenosis is unclear and is based

on surgeon and patient preference

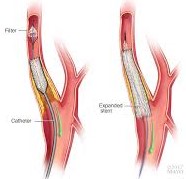

- Endovascular Therapy

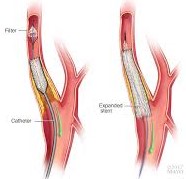

- balloon angioplasty and stent placement (CAS) are an alternative to CEA

- potential benefits of CAS include lower incidences of incisional pain, cranial nerve injury, wound infection,

and neck hematoma

- CREST trial was designed to compare the safety and efficacy of CAS and CEA in symptomatic and

asymptomatic patients

- CREST Trial

- primary endpoints were any stroke, MI, or death in the perioperative period; or ipsilateral stroke

in the follow up period

- CAS and CEA had equivalent total complications (7.2% for CAS, 6.8% for CEA)

- however, 30-day stroke rate was significantly higher in the CAS group (4.1% CAS, 2.3% CEA)

- perioperative MI rate was significantly higher in the CEA group (2.3% CEA, 1.1% CAS)

- at one year postop, stroke had a more detrimental impact on quality of life than MI or cranial nerve injury

- Indications and Contraindications

- Indications

- lesion not amenable to surgical access

- radiation-induced stenosis

- restenosis after CEA

- hostile neck anatomy

- Contraindications

- coiling or kinking of the ICA or CCA

- tortuous or calcified aortic arch

- difficult iliac access

- Technical Considerations

- Access

- retrograde common femoral artery is the first choice

- brachial access is only used in cases of severe aortoiliac disease

- transcarotid revascularization is an emerging technique that accesses the carotid through a

small neck incision

- Embolic Protection Devices

- routinely used during CAS, but no trial has documented their efficacy

- a balloon or filter is deployed in the distal ICA

- Carotid Stent Placement

- a self-expanding stent is deployed across the plaque from the ICA into the CCA, covering the

origin of the ECA

- prestenting angioplasty is not performed unless it is necessary to create a space in

near-occlusive lesions

- a stent that does not oppose the carotid wall may serve as a nidus for thrombus formation

- Carotid Angioplasty

- performed after stenting

- balloon can only be inflated within the stented artery segment

- goal is to achieve a residual stenosis of < 30%

- Completion Angiogram

- necessary to document adequate resolution of the carotid disease and flow through the ICA

References

- Schwartz, 10th ed., pgs 837 - 850

- Sabiston, 20th ed., pgs 1789 - 1796

- Cameron, 13th ed., pgs 928 - 933, 939 – 946

- UpToDate. Management of Symptomatic Carotid Atherosclerotic Disease. Ronald M. Fairman. Aug 11, 2020. Pgs 1 – 44

- UpToDate. Management of Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerotic Disease. Ronald M. Fairman. Dec 21, 2020. Pgs 1 – 37