Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

- Anatomy

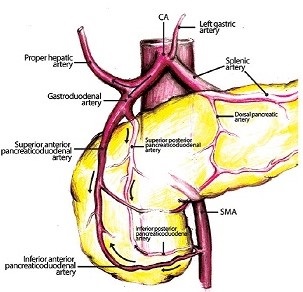

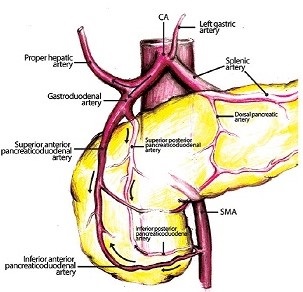

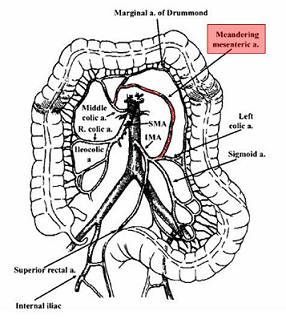

- Arterial Circulation

- 3 main arteries supply the GI tract

- there is an extensive collateral network between these arteries

- Celiac Artery (CA)

- supplies the foregut – distal esophagus, stomach, liver, spleen, duodenum

- arises from the ventral aspect of the infradiaphragmatic aorta

- surgical exposure requires division of the crura and median arcuate ligament

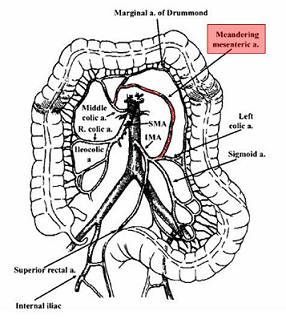

- Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA)

- supplies the midgut – from the jejunum to the mid transverse colon

- arises from the ventral infradiaphragmatic aorta just below the celiac artery

- on angiography, to fully visualize the origins of the CA and SMA, a lateral view must be obtained,

as well as an AP view

- Inferior Mesenteric Artery

- supplies the hindgut – from the mid transverse colon to the rectum

- arises from the lateral aspect of the of the infrarenal aorta

- Collateral Circulation

- superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries are the primary collateral network between the CA and SMA

- the SMA and IMA are linked by the arc of Riolan centrally, the marginal artery of Drummond on the periphery

of the colon, and unnamed retroperitoneal vessels

- the IMA and systemic circulation are linked by the internal iliac artery and the hemorrhoidal arteries

- Pathophysiology

- in chronic mesenteric ischemia, gradual occlusion of 2 vessels is usually tolerated because the collateral network

has time to grow and develop

- in acute mesenteric ischemia, occlusion of one main vessel is often sufficient to cause profound ischemia because

the collateral network is undeveloped

- SMA Embolus

- most common etiology of acute mesenteric ischemia (50%)

- most emboli originate from the heart as a result of atrial fibrillation or a myocardial infarction

- emboli preferentially lodge in the SMA because of its high flow rate, large diameter, and nearly parallel

course to the aorta

- most emboli lodge 3 to 10 cm distal to the SMA origin

- proximal jejunum is usually spared

- SMA Thrombosis

- accounts for 20% of cases

- occurs at the origin of the vessel

- chronic aortic and mesenteric atherosclerosis is present and patients often have a history of chronic

mesenteric ischemia (acute-on-chronic ischemia)

- involvement of at least two of the major mesenteric arteries is required for symptom development

- patients often have significant collateral circulation

- entire midgut will be ischemic

- Nonocclusive Mesenteric Ischemia

- 20% of cases

- caused by a low-flow state resulting from shock, vasopressor use, or hypovolemia

- mesenteric vessels may be normal

- mortality rate is high because of delay in diagnosis and the underlying medical condition of the patient

- Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis

- 10% of cases

- SMV is most commonly involved (70%); the portal vein, splenic vein, and IMV account for the other 30%

- venous thrombosis leads to bowel wall edema and decreased perfusion

- primary risk factors include hypercoagulable states such as protein C or protein S deficiency

- secondary risk factors include malignancy or recent abdominal surgery (splenectomy)

- Clinical Presentation

- SMA Embolus

- sudden, severe periumbilical pain out of proportion to the physical exam

- nausea/vomiting and bowel emptying are common, but bloody diarrhea is rare

- many patients are in atrial fibrillation or have had a recent MI

- SMA Thrombosis

- symptoms are often less dramatic than for an SMA embolus

- patients typically have a history of intestinal angina and weight loss from ‘food fear’

- patients may report worsening postprandial pain

- Nonocclusive Mesenteric Ischemia

- ischemic symptoms may be overshadowed by the patient’s underlying medical condition

- ICU patients may present with progressive abdominal distention and acidosis

- Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis

- slow to diagnose because the abdominal pain is often episodic and not very severe

- Diagnosis

- requires a high index of suspicion

- EGD and colonoscopy are of no value in the acute setting

- barium enema is contraindicated if intestinal ischemia is suspected

- Laboratory Tests

- common, but nonspecific, findings include leukocytosis, hemoconcentration, and an elevated serum lactate level

- normal lab findings do not exclude intestinal ischemia

- Plain Abdominal X-rays

- useful for ruling out a perforated viscus or intestinal obstruction

- suspicious findings for infarcted bowel include bowel wall thickening, pneumatosis intestinalis, or

portal venous gas

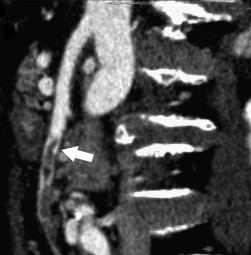

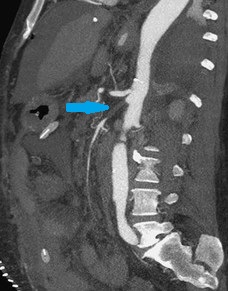

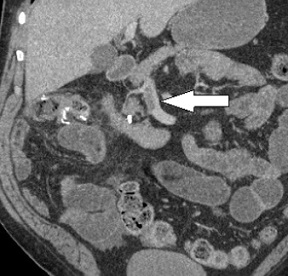

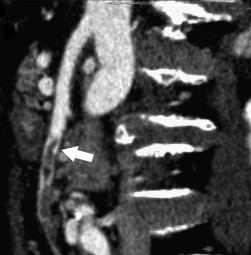

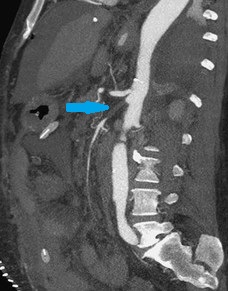

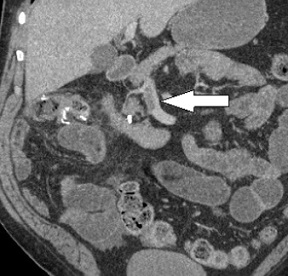

- CT Angiography

- definitive diagnostic study and should be ordered promptly if mesenteric ischemia is suspected

- should be done without oral contrast, which can obscure the mesenteric vessels and obscure bowel wall enhancement

- emboli show an abrupt cutoff several centimeters from the SMA origin, typically at the middle colic orifice

- SMA thrombosis occurs at the origin of the vessel, and extensive collateral networks are often seen

- nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia will show a normal SMA with diffuse vasospasm of the mesenteric arcades

- catheter angiography also has a therapeutic role in infusion of catheter-directed vasodilator agents

- mesenteric venous thrombosis is diagnosed by the presence of venous filling defects on delayed imaging

- Management

- Initial Management

- fluid resuscitation

- correction of metabolic acidosis, with sodium bicarbonate if necessary

- antibiotics

- systemic heparinization to prevent thrombus propagation

- avoid vasopressors if possible

- SMA Embolus

- embolectomy proceeds bowel resection

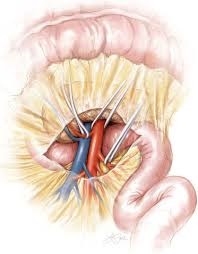

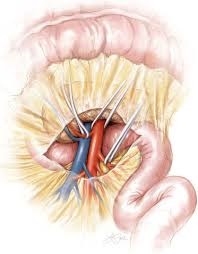

- SMA is found at the root of the mesentery where it passes over the third portion of the duodenum

- if the artery is not diseased, a transverse arteriotomy is made; otherwise a longitudinal arteriotomy is made

- a Fogarty catheter is passed proximally and distally to remove the embolus

- a transverse arteriotomy can be closed primarily; a longitudinal arteriotomy is closed with a vein or synthetic patch

- bowel viability is assessed once flow has been restored, and obviously necrotic bowel is resected

- Doppler assessment of antimesenteric pulsations or IV fluorescein followed by Wood lamp inspection can

assist in determining bowel viability

- if bowel viability is questionable, it is left in discontinuity and a second-look procedure is done 24 – 48 hours later

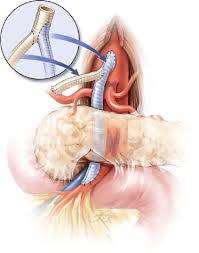

- SMA Thrombosis

- origins of the CA and SMA are severely atherosclerotic

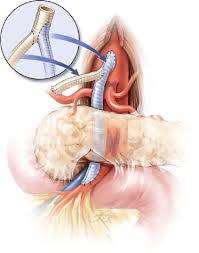

- mesenteric bypass to a distal uninvolved segment is necessary for revascularization

- single-vessel or two-vessel bypass may be performed

- reversed saphenous vein or PTFE reinforced with rings may both be used as conduits

- may be done in an antegrade or retrograde fashion

- Antegrade Bypass

- uses the supraceliac aorta, which is usually uninvolved by atherosclerosis

- allows the use of a short graft, which resists kinking when the bowel is returned to its

normal position

- revascularization of the CA is usually performed to the common hepatic artery

- disadvantages include difficult exposure and the need for supraceliac aortic occlusion

- Retrograde Bypass

- uses the infrarenal aorta or iliac artery for inflow

- advantages are the ease of exposure and no supraceliac aortic occlusion

- disadvantages include the use of inflow vessels that are usually heavily involved in atherosclerosis,

and a long graft that is easily kinked

- Nonocclusive Mesenteric Ischemia

- management is by catheter-directed infusion of a vasodilatory agent, usually papaverine

- patients are also heparinized

- all vasoconstricting agents must be stopped

- laparotomy will be required if peritonitis develops

- SMV Thrombosis

- fluid resuscitation and anticoagulation are the primary treatment modalities

- venous thrombectomy has not been shown to be effective

- surgery is limited to bowel resection in patients with peritonitis

- patients with abdominal pain but who do not have peritonitis, may benefit from catheter-directed

thrombolytic therapy

- the mesenteric venous circulation is reached by catheters placed in the splenic artery and SMA

- Endovascular Treatment

- can only be used in cases where there is a very low suspicion for gangrenous bowel

- most useful in SMA thrombosis

- catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy is first used to dissolve the thrombus

- the diseased artery may then be treated with balloon angioplasty and stenting

Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia (CMI)

- Pathophysiology

- most common cause is atherosclerotic arterial occlusive disease

- usually related to compromise of flow in both the CA and SMA

- most mesenteric atherosclerotic lesions are located at the vessel orifices

- the involvement of the mesenteric vessel is usually limited to the first 1 to 2 cm of the main trunk

- Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- postprandial abdominal pain (intestinal angina), ‘food fear’, and profound weight loss

- precursor to SMA thrombosis and intestinal infarction

- definitive diagnosis requires CT angiography, which will typically show occlusion of the CA and SMA at their origins

- Management

- Endovascular Procedures

- most vascular surgeons consider endovascular techniques to be procedure of choice for patients with CMI

- associated with lower rates of morbidity and mortality and shorter lengths of stay than open surgery

- long term patency rates are lower than that achieved by open surgery and more secondary procedures for

restenosis are required

- Mesenteric Bypass

- similar decision-making and technical considerations as for acute SMA thrombosis – antegrade versus

retrograde bypass

- both the CA and SMA are usually reconstructed in the chronic setting

- Transaortic Endarterectomy

- aorta is exposed with medial rotation of the viscera from the left

- U-shaped trapdoor aortotomy is made to encompass the origins of the CA and SMA

- endarterectomy is performed starting on the aorta and extending into the visceral artery orifices

- technique is most applicable to lesions limited to the first 1 to 2 cm of the visceral artery

- aortic clamp time greater than 40 to 45 minutes can result in hepatic ischemia and irreversible coagulopathy

- has largely been replace by endovascular techniques and open bypass

References

- Schwartz, 10th ed., pgs 859 – 866

- Cameron, 13th ed., pgs 1057 – 1061, 1062 - 1067

- UpToDate. Overview of Intestinal Ischemia in Adults. David A. Tender, MD, J. Thomas Lamont, MD. Jun 01, 2020.

Pgs 1 – 33

- UpToDate. Acute Mesenteric Arterial Occlusion. Gregory Pearl, MD, Ramyar Gilani, MD. Apr 07, 2020. Pgs 1 – 31